THE GREEN LINE

ORIGINAL STORY

How This Wychwood Garden Is Reconnecting Urban Indigenous Communities in Toronto with the Land

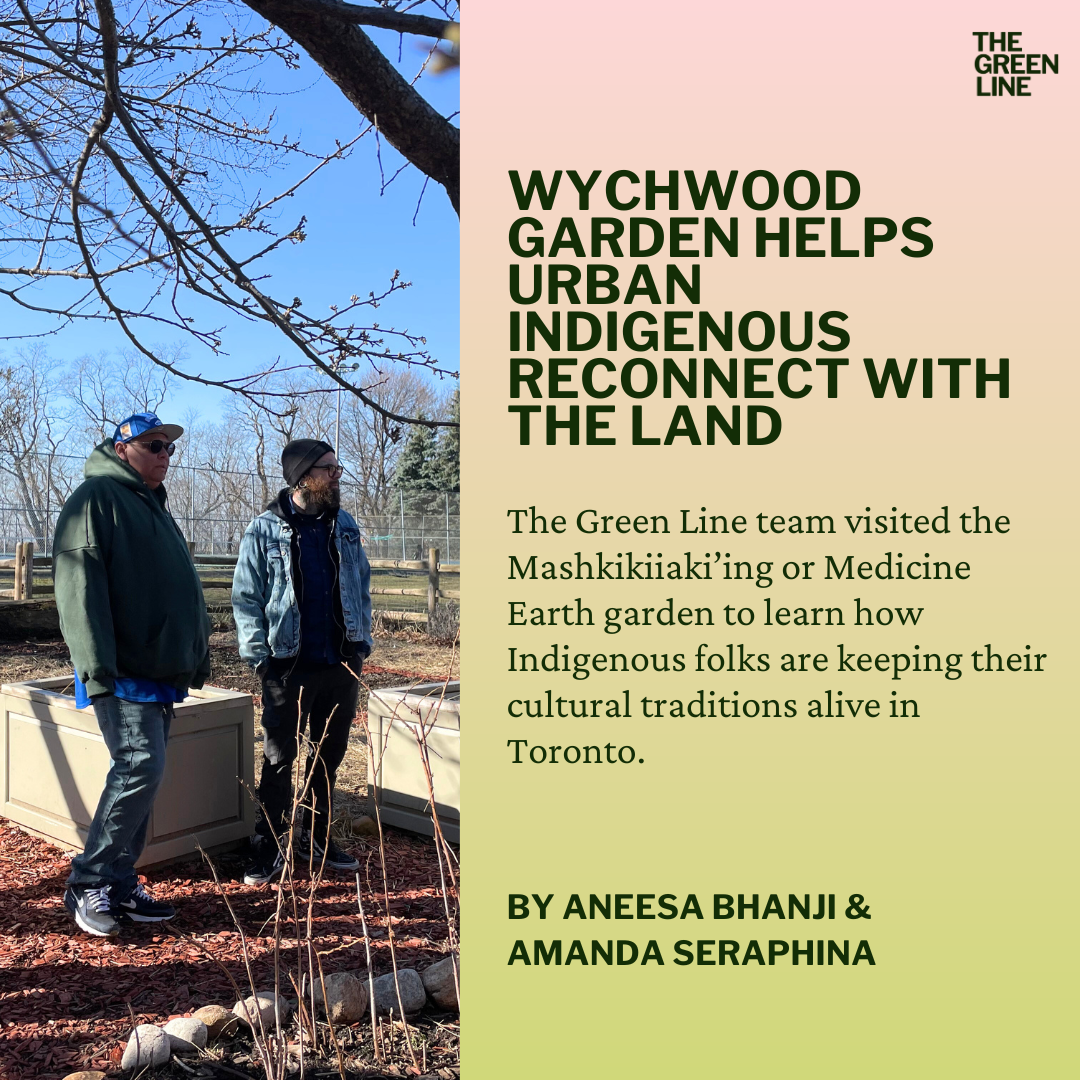

The Green Line team visited the Mashkikiiaki’ing or Medicine Earth garden to learn how Indigenous folks are keeping their cultural traditions alive in Toronto.

Big Thunder (pictured left) and Karl Cousineau (pictured right) stand in front of the Mashkikiiaki'Ing garden in Hillcrest Park.

ANEESA BHANJI

Currently a journalism student at Toronto Metropolitan University who's also studying communication and design. Grew up in Vaughan, now living in downtown Toronto. Always loves a good chai latte.

AMANDA SERAPHINA JAMES RAJAKUMAR

Indian immigrant with a post-grad in journalism from Centennial College. Now living in Grange Park, meeting new people, and hearing different stories. Has four names, so it’s a pick-your-player situation.

May 3, 2024

Although it's only a few subway stops from the downtown core, the neighbourhood of Wychwood is a lot less hectic.

Among its many green spaces is the Mashkikiiaki'ing, or Medicine Earth garden, a community space run by Indigenous people for Indigenous people.

Thanks to a partnership between the Native Men's Residence (Na-Me-Res) and The Stop Community Food Centre, men from the shelter can come to the garden to grow traditional medicine, make sacred fires and learn how to harvest their own food.

“We have all the stuff that we need for our ceremonies, but we also show the guys how to grow the green peppers, cabbages [and] stuff like that, so that they have different things that they can take home with them,” says Big Thunder (John Laforme), life skills coordinator at Na-Me-Res.

The word Mashkikiiaki'ing translates to “new beginnings,” which Big Thunder, who’s a member of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, says is what the garden provides men at the shelter.

“With regard to our neighbours here, it means building a relationship because there's all of that systemic criticism — of people being homeless, coming out of jails, coming from different areas of life — that a lot of our community feels all the time,” he explains. “We’re not all bad people. People do make changes. People make mistakes. We're here to do something different."

Open to all local Indigenous, Inuit and Métis peoples, Mashkikiiaki'ing has been in Wychwood for over 20 years.

Karl Cousineau stands in the Mashkikiiaki'Ing garden in Hillcrest Park.

Karl Cousineau, who’s Métis, has been coming to the garden since he was 19. It's become Cousineau’s ideal spot for reflection, where he often sits to watch the birds.

“You get to meet a lot of people in the community. So, sometimes when I do feel a little bit down or lonely, I will just sit over here and somebody will come up to me and ask me about the plants or what this garden actually is,” he says.

“I realize a lot of the mistakes that I've done in the past….I’m working on a lot of things like accountability, and being at a garden like this — nothing happens instantaneously. So, it's always coming back and tending to the flowers or the plants or the medicines."

Magpie Arancibia, Mashkikiiaki'ing’s program coordinator and a member of the Mapuche Nation in South America, says his goal is to keep cultural traditions alive among urban Indigenous in Toronto.

"It's to help the men who are in healing at Na-Me-Res to get a land-based style of teaching, more so in the sense of moving away from institutionalized ways and more to their traditional ways,” Arancibia says.

He adds that he makes a point of teaching participants how to grow their own food and to provide them with urban agricultural knowledge, while also helping them learn about their cultural traditions, like traditional medicines.

Mashkikiiaki'ing garden coordinators Samuel Wong (pictured left) and Magpie Arancibia (pictured right) stand in The Stop’s greenhouse.

Big Thunder says Mashkikiiaki'ing helps urban Indigenous people continue the tradition of caring for the land in the city.

“We're not just here as visitors; we're here as the caretakers because I know our teachings. We don't own nothing,” he explains. “We're the ones that take care of the lands, and that's what we do here.”

Ultimately, Big Thunder hopes there will be more spaces like Mashkikiiaki'ing for Indigenous people in Toronto.

“You have other little gardens around the city, like different churches have got the medicines and stuff. But this is one of the only ones that has all the medicines, and it's run by the Indigenous community; so, I mean, it's very unique. I think there should be more in the city," he says.

Fact-Check Yourself

Sources and

further reading

Don't take our word for it —

check our sources for yourself.