PART 1

A HISTORY OF BLACK FILM IN THE CITY

IAN KAMAU'S COLLECTION OF CAMERAS.

SHAKI SUTHARSAN

Toronto native and Tamil-Canadian who's currently studying journalism and public relations at Toronto Metropolitan University. Writer and avid consumer of fiction. Boyband loyalist.

February 6, 2023

In Canada, the first movie directed by a Black filmmaker debuted in 1975.

That's more than 50 years after The Homesteader (1919), directed by Oscar Micheaux — also a Black filmmaker — was released in the United States.

Despite its extensive artistic roots, Black cinema in Canada hasn't had the same kind of institutional support that it's enjoyed in America. A lack of investment in Black-produced television and film is one reason why.

Claire Prieto-Fuller sits in the rocking chair where she used to sit with her son Ian Kamau when he was a child.

Directed by Claire Prieto-Fuller, Some Black Women came out in 1975 in Canada. It was a short film about the lives of Black women in Canada as "creative beings."

After the film's release, there was a decades-long pause during which Black film in Canada consisted of short films and documentaries, but not full-length features.

Why? Toronto-based Black creatives we interviewed say there's a systemic lack of support for Black stories and audiences.

"If you don't value the talented people in your city, they'll leave— and they should."

IAN KAMAU

FILMMAKER AND ARTIST

"If you don't value the talented people in your city, they'll leave— and they should," said Ian Kamau, the son of Prieto-Fuller and a prolific Toronto-based artist.

"There's really no infrastructure here [for artists], certainly not for Black people."

According to the Canadian Media Producers Association's 2020-21 "Economic Report on the Screen-Based Media Production Industry in Canada," our film and television industry generated $9.09 billion in production volume, contributed $11.27 billion to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and created close to 217,000 jobs.

But those numbers fell from 2019-20 due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. There was an 5 per cent drop in the revenue generated in production value, 10 per cent less contributed to our GDP and 11 percent fewer jobs created.

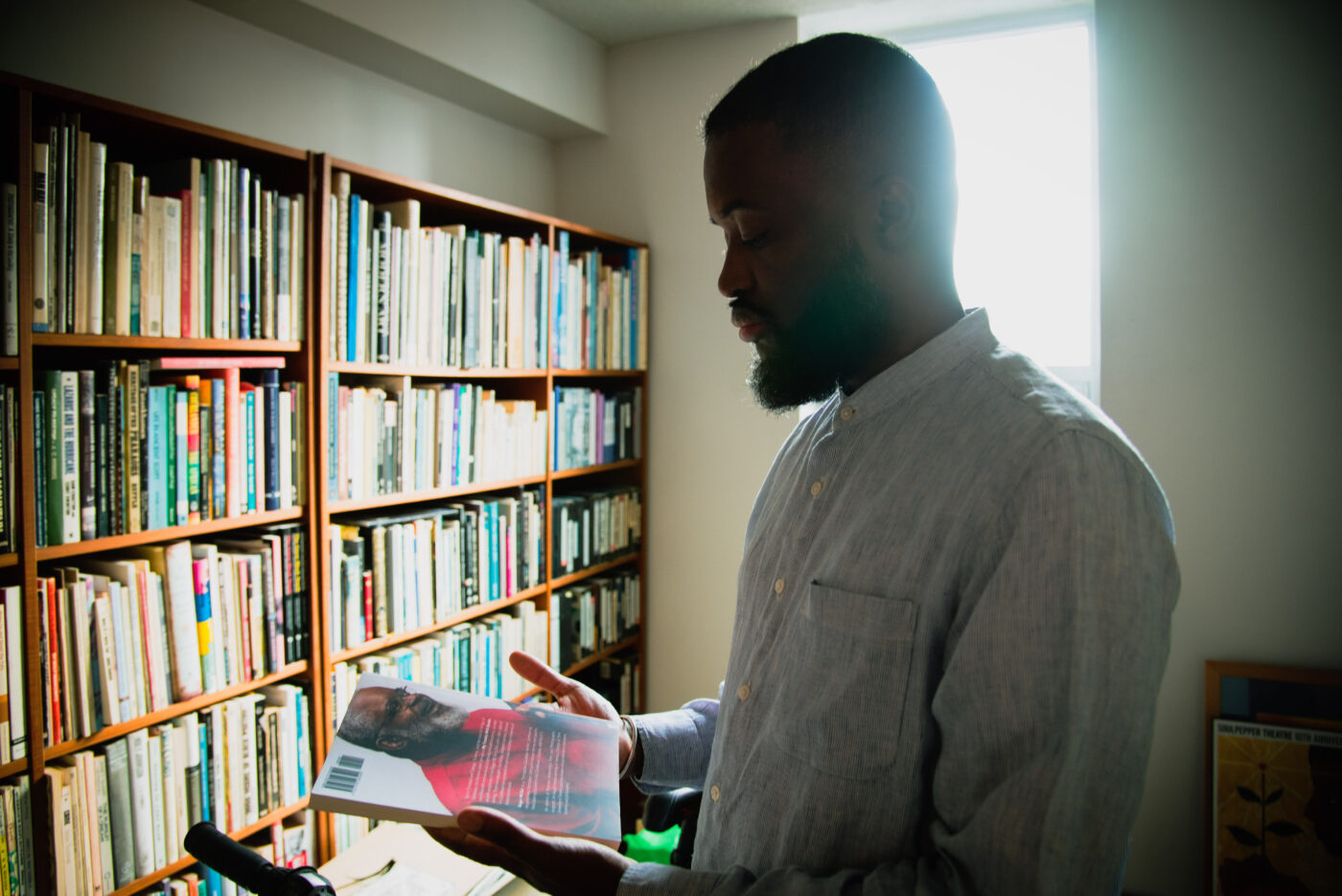

Ian Kamau holds an advance copy of a book written by his father, Roger McTair.

After the two-decade-long pause, there was a breakthrough in the mid-1990s with the release of Clement Virgo's Rude (1995), a feature film about the experience of growing up in Regent Park.

That was followed by Stephen William’s Soul Survivor (1995) and Christine Browne’s semi-autobiographical work, Another Planet (1999). Browne was the first Black woman to write, produce and direct a feature film in Canada. Both Virgo and Williams later moved to the U.S. to write for major TV series, including Lost and The Wire.

Ian Kamau and Claire Prieto-Fuller survey the penthouse meeting room where members of the Black Film and Video Network gathered.

In 1988, Prieto-Fuller launched the Black Film and Video Network (BFVN), a collective of Black artists that gave Browne, Virgo, Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) CEO Cameron Bailey and other industry leaders their first opportunities to network and connect with like-minded industry peers throughout the 1990s.

BFVN provided an organized network from which the legacy of Black film in Toronto and beyond would continue to grow.

But despite the creation of a strong foundation for Black cinema in Canada, the lack of investment on an institutional level is an ongoing issue.

In 2020, several Black professionals in Canada's entertainment industry signed an open letter asking former federal Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault to address the "systematically racist polices" that they said were at the root of the brain drain in Canadian entertainment.

In response, Telefilm Canada, which is one of the country's primary film funders, pledged an annual fund of $100,000 to help create more job opportunities for Black creators and professionals working.

Outside of the penthouse meeting room where members of the Black Film and Video Network gathered, Claire Prieto-Fuller looks over the rooftop garden.

Recently, there's been a slow increase in Black film productions in Canada that have gained national recognition, such as Akilla's Escape (2020), which won five Canadian Screen Awards last year.

But Black creatives we interviewed say there's still much work to be done to establish the necessary local infrastructure to support Black and other racialized filmmakers in Toronto.

Today’s stories lead to tomorrow’s solutions, so sign up for our newsletter to take action on the issues you learn about in The Green Line.

PART 2

How Two Black Women Filmmakers From Toronto Created a Community That Launched the Black-Canadian Film Canon

HUDA HASSAN

Writer from Scarborough, Black feminist cultural studies scholar and eldest daughter. Currently examining the connections between art, place-making and power.

February 13, 2023

Plants surround the space that Ian Kamau now uses as a music studio.

It’s a warm July day in Toronto, and Ian Kamau is sitting in the childhood home where he was raised by his parents, Claire Prieto-Fuller and Roger McTair.

For Kamau, they’re the beginning of his story: the two people who taught him how to walk, talk and survive in a difficult city. To the rest of the local arts community, though, Prieto-Fuller and McTair are pioneering Black filmmakers in Canada.

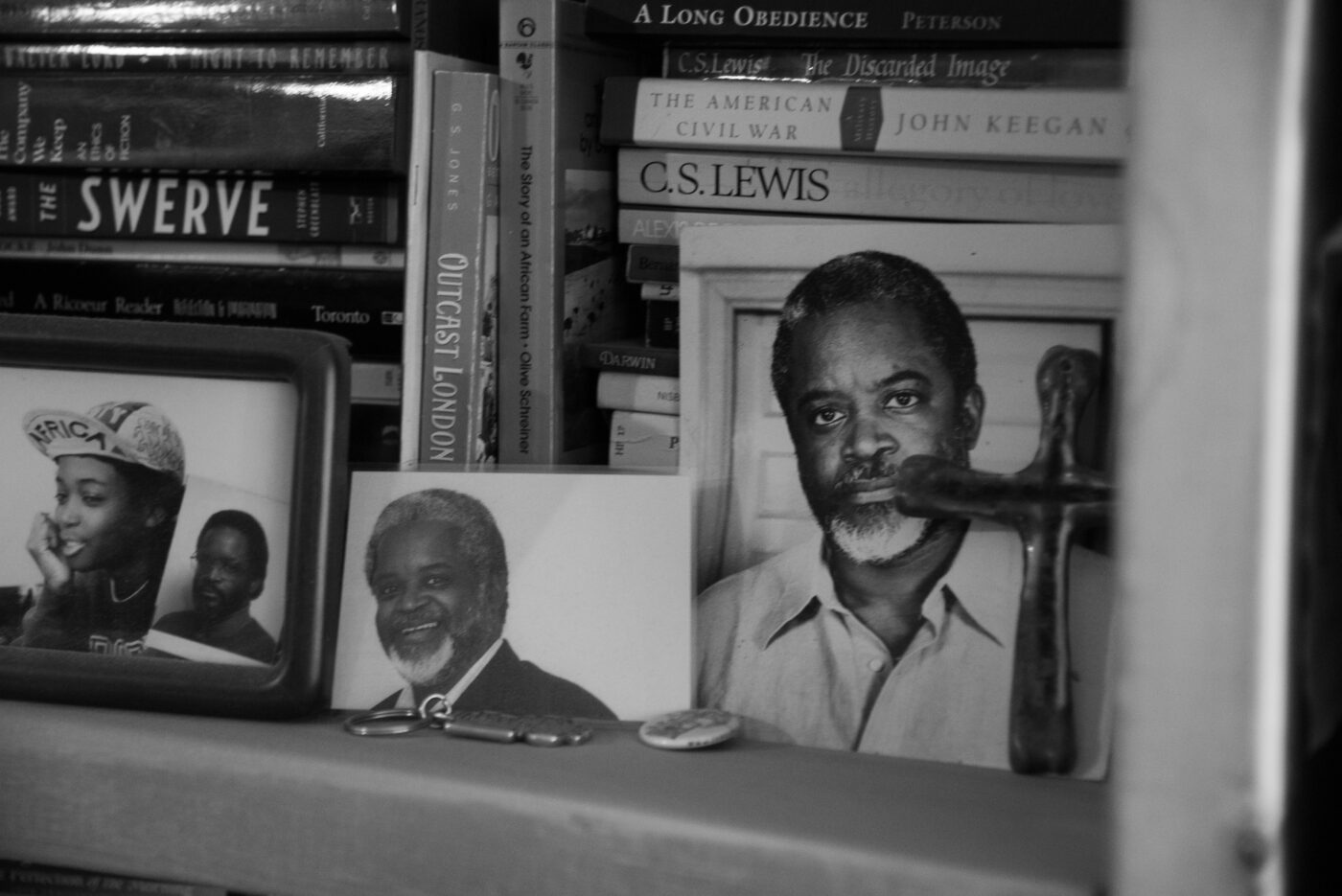

Rich with art and literature, Kamau’s home is inviting to the curious eye. His workspace — once his mother’s — is a plant-dotted sunroom with large windows and a view of The Esplanade facing south. Next to the sunroom is a bookshelf with hundreds of books from the family’s collection, including Antonia White’s 1954 novel Strangers, which explores the borderlands of belief, loss of faith, love and grief. These themes symbolize the way this family of artists think about their craft and the world.

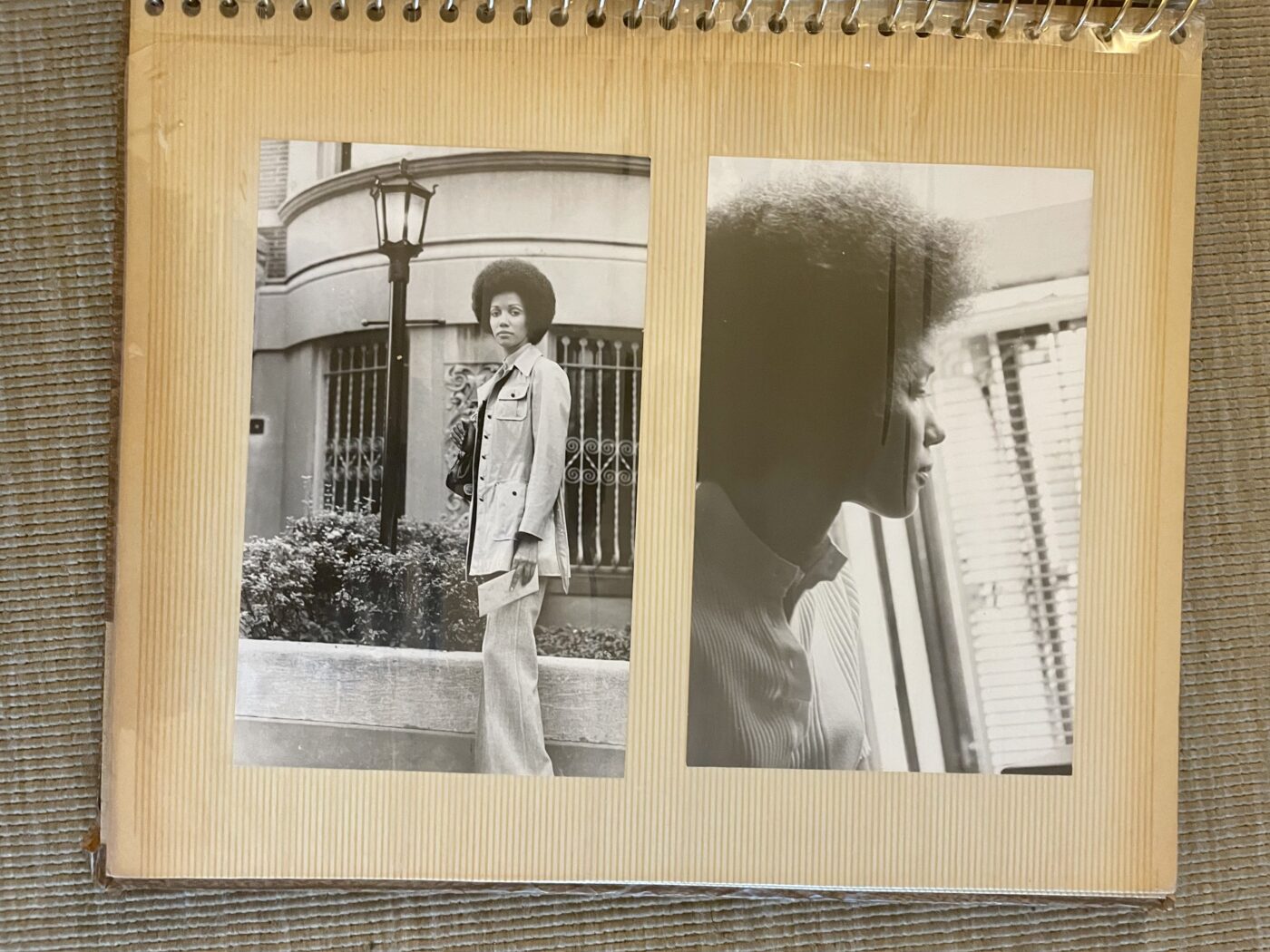

A black-and-white portrait of Prieto-Fuller that was taken by Roger McTair when they were both students at Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson).

In front of the shelves on top of some boxes sits a large, unframed black-and-white portrait of Prieto-Fuller that was taken by McTair when they were both students. They’d met at Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson) where she was studying film and he was learning photography.

“I feel like a lot of my creativity and intellect — my love for writing and photography and visual things — emanated from conversations with my father,” says Kamau, a prolific artist, writer and designer in Toronto. “But my mom is the genesis of my art — the genesis for the entire way that I think about the world.”

BECOMING A PIONEER

It was shortly after the end of World War II when Americans were able to watch their first feature film created by a Black director: Oscar Micheaux’s The Homesteader (1919).

Meanwhile, in Canada, the first movie directed by a Black filmmaker wouldn’t arrive until 56 years later in 1975.

That’s when Prieto-Fuller, a Trinidad-and-Tobago-born filmmaker and longtime Toronto resident, released Some Black Women, a short film she produced and McTair directed that explores the intersectional experiences of Black Canadian women in the ‘70s, examining their lives as creative beings. It encapsulates the core focus of Prieto-Fuller’s body of work: an unwavering commitment to storytelling about the nuances of Black lives in Canada.

But finding resources to create this kind of film was no easy task.

“I remember going to the film board looking for money for [Different] Timbres” Prieto-Fuller says over the phone, as she describes her 1980 short film about the politics of the steelpan. “I know my proposal basically said [the film] was about music. It was obviously a film about Black people. I didn't say that, though. I said it was about music: the steelpan. And, of course, that's who played that stuff. [We were] told that they were not interested.

“[When I asked] why, they said, ‘Well, we put some money into a Black project last year.’”

These roadblocks motivated Prieto-Fuller to cultivate the resources and build the community necessary to lift up future generations of Black-Canadian filmmakers, starting with her son.

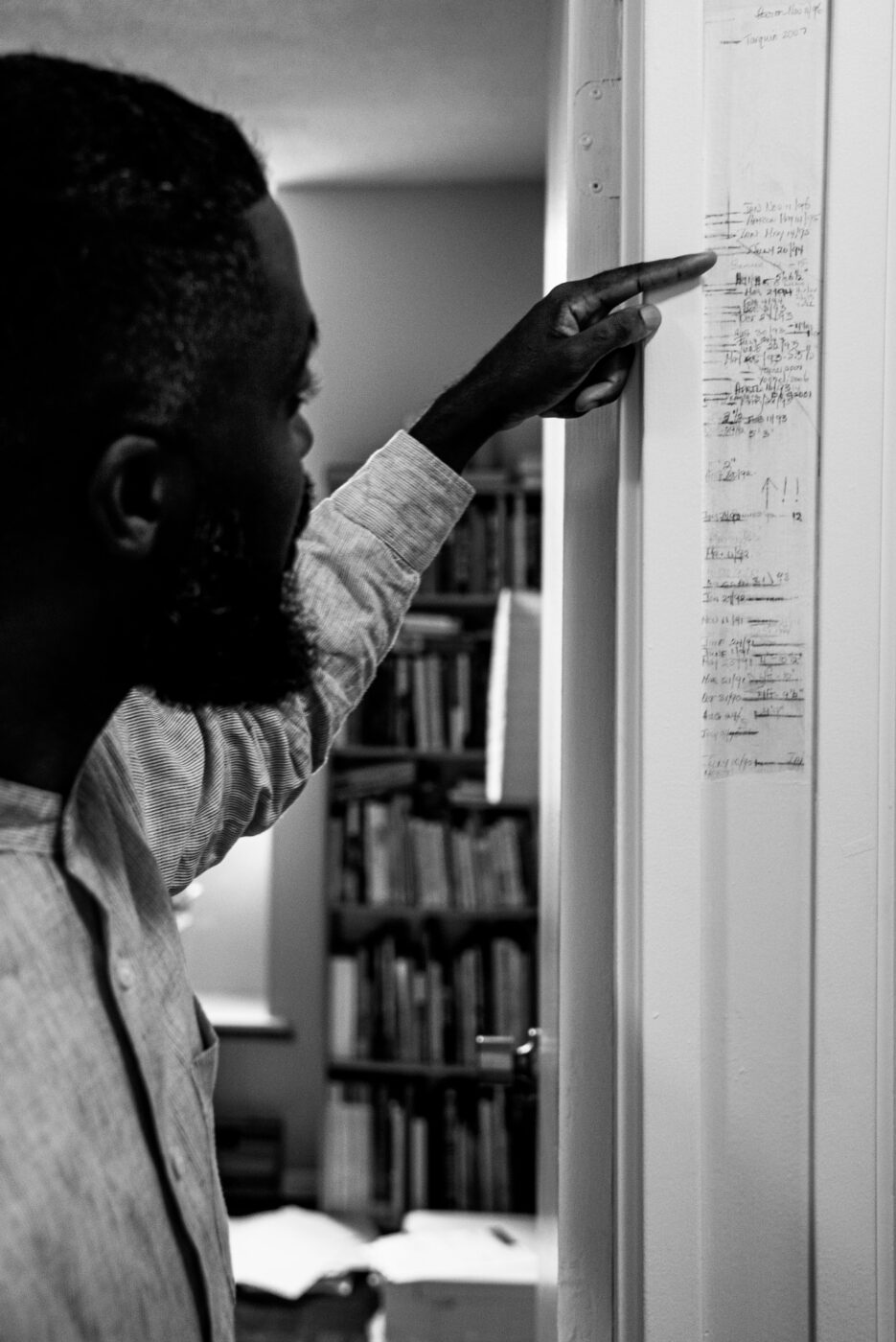

Ian Kamau points at the wall on which his family measured his and his cousins’ heights as they grew up in the 1990s.

“I did not have a moment of becoming an artist,” Kamau says, gesturing to the splatter of paint on the ceiling of his childhood home. “I always was one. I mean, look up.

“I was 4 years old when I did that.”

When Prieto and McTair created Some Black Women, they were young artists living in Parkdale. The couple raised Kamau there until the mid-1980s, then later moved to The Esplanade. In the same house that Prieto-Fuller and McTair created nine documentaries and shows, from 1982 to 2007, Kamau produced three LPs, two EPs, and countless works of audio and visual art. He also co-founded Nia Centre for the Arts, one of Toronto’s few spaces dedicated to supporting Black artists.

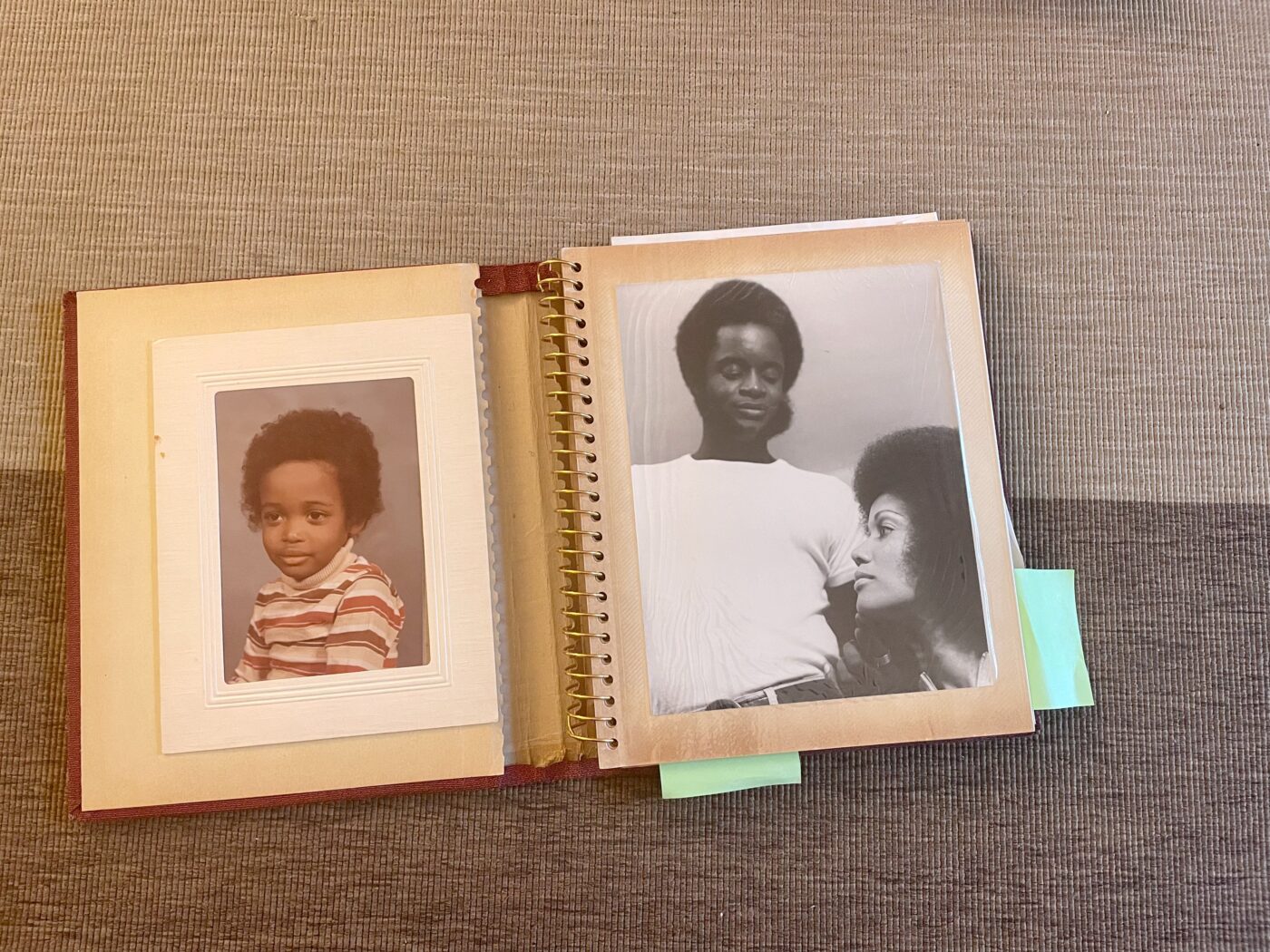

Photos from a family album of Claire-Prieto Fuller as a young filmmaker.

“We're not talking [about my parents creating] digital stuff,” Kamau explains while sitting on the same rocking chair his mother used when he was a toddler. “We're talking about film stock in the 1970s. That costs money for people that didn't have money — who were basically new to the country — like my parents who started making films within the 10 years they got here.”

Kamau also recently directed his second short film, 2021’s We Went Out in which he guides viewers through archival footage of his upbringing in downtown Toronto during the ‘90s and ‘00s. It features a narrative poem about place, belonging and living in between public spaces of the city from the perspective of children from working class households. “I never had a backyard, front yard or a basement. I had stairways, hallways, parks and benches; a living room for us, a little room for me” is a line that Kamau repeats throughout the film.

Much like how Prieto-Fuller encouraged her son’s artistic sensibilities, Kamau explains how much mentorship has been central to his mother’s legacy.

“My mother actively was involved in supporting people, whether it was something that was out in the open, or someone who came by the house on a regular basis,” he says. “My mother is a very future-oriented person…and being future-oriented means supporting the people that are around you — but also the generations of people that are coming up behind you.”

It was at their Tyndall Avenue home in Parkdale, on a street populated by a small diaspora from Trinidad and Tobago, where Prieto-Fuller and McTair created an artistic enclave. Their apartment became a hub for Black artists and community organizers from across Toronto, including filmmaker Jennifer Hodge de Silva, feminist writer Makeda Silvera, and poets Clifton Joseph and Dionne Brand.

By 1985, when Prieto-Fuller and McTair began working on a documentary about Black-Canadian lives in a small Ontarian town called Home to Buxton (1987), the family moved from their diverse, working-class street in Parkdale to the multiracial Esplanade neighbourhood. It was there that they made nine films and documentaries about Black life in Canada, cementing themselves as pioneers in film and television.

Across the expanse of Canada’s 48-year Black film canon, Prieto-Fuller’s name continuously pops up at the centre of it all.

“She was the queen of Black-Canadian film, as far as we knew,” says Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) CEO Cameron Bailey. “Claire was who we looked up to to help us figure out how to open up some space for more Black people.

“She was very connected to her Caribbean identity and culture, and also felt, to me, like a real pan-Africanist. That was an important kind of movement to me at the time. It did feel like you were entering a space that didn't exist on the film side of Toronto.”

Claire Prieto-Fuller smiles while recounting a story from her early years as a filmmaker in Toronto.

STRUGGLE FOR

A COMMUNITY

After working on 1983’s Home Feeling: Struggle for a Community, Jennifer Hodge de Silva, another seminal filmmaker in Canada’s film canon, developed a friendship with McTair.

At the time, she lived just north of Parkdale on Concord Avenue with her husband, Paul de Silva who’s now co-director of the International Diaspora Film Festival and professor of film and media studies at the Toronto Film School.

Jennifer, who died from cancer in 1989, moved to Toronto in the ‘70s from her native Montreal after living a life abroad. Her mother, Mairuth Sarsfield, was a Canadian journalist, activist and best-selling author who was the first Black woman to serve on CBC’s board of governors. Sarsfield’s international work as a journalist took Jennifer around the world throughout her childhood. As a result, Jennifer received her education in Switzerland at a school inspired by Austrian spiritualist Rudolf Steiner, and lived across Europe.

The young filmmaker's upbringing across continents introduced her to a world of different histories, languages, perspectives and aesthetics. She was fluent in German, English, French and “a bit of Italian,” according to her husband Paul. Jennifer was also the stepdaughter of photographer and designer Rudi Haas, who taught her how to use cameras, play with lighting and the importance of aesthetics. Her stepfather Terence Macartney-Filgate, a British-Canadian film director who shot more than 100 films during his 50-year career, influenced how she produced documentaries visually.

After moving to Toronto, Jennifer studied film at York University. In 1979, she released her first documentary, Canada Vignettes: Helen Law, a profile of a Chinese immigrant woman through the eyes of her first-generation Canadian son. Jennifer also made films about Indigenous artists Bill Reid, Joe David and Dennis Highway, before co-directing her seminal work in 1983, Home Feeling: Struggle for a Community — a collaboration with her friend and peer, McTair.

Before getting married in 1982, Jennifer met Paul during the late ‘70s in an elevator in a former CBC building located at the intersection of Church and Maitland Streets. The building was informally known as “Mac’s Milk” among regulars because it was located atop one of the convenience stores. Back then, Paul was a television reporter.

“We [were] going up to the third floor, on our way to our first meeting for a television series,” Paul says from the Bloordale home he previously lived in with Jennifer. They’d been hired for a show called Canadians, a documentary series about the growing diversity of Toronto’s expanding communities.

“There was a stunning-looking, beautiful, tall Black girl in the elevator. I looked at her and she looked at me and, you know, we sort of nodded,” he adds with a laugh.

Shortly after starting their relationship, Jennifer began working with McTair on Home Feeling, which Paul says was her last major film before her death. It explores the tensions between Black community members and Toronto Police Service officers in the neighbourhood of Jane and Finch. Home Feeling stands out because of its keen ability to show the mundane, day-to-day cruelties imposed on the community.

Family photos of Ian Kamau (pictured far left wearing a cap) and his father Roger McTair.

Ian Kamau listens to his father, Roger McTair, tell stories about his time at Ryerson University (now Toronto Metropolitan University).

The police officers in Home Feeling, you quickly sense, are not media-trained nor are they media-conscious. In fact, they don’t seem to care for the camera. As viewers can see in the documentary, the officers do very little to hide how they move through a lower-income and racialized community. For Black Canadians in Toronto, Home Feeling is a seminal work that reveals ongoing police brutality.

Upon its release, Paul says the Toronto Police Service and local politicians took issue with the film, complaining about the portrayal of racial and class biases among members of the police force.

“After Home Feeling was released, the police were not happy with it. It didn't shed [light on] them very well,” he explains. “She was being followed at a certain point when we were living together.”

The same year the film came out, Jennifer lost her brother, Jeremy Hodge, who died after he crashed into a snowy lake. A few years after Home Feeling’s debut, Jennifer and Paul had their first child, Zinzi de Silva, an artist now based in the Dominican Republic. But in 1986, Jennifer was diagnosed with cancer; she died in 1989 when Zinzi was 4 years old.

Paul says Jennifer’s empathy, as well as her ability to understand the pain and perspectives of others, drew people in.

“She had this sensitivity and shyness,” he explains. “She wasn't bombastic and she didn’t lack confidence. People could feel her sensitivity and that's why, in many ways, Home Feeling is special — because people trusted and opened up to her.”

Jennifer Hodge de Silva as a young filmmaker.

TIFF CEO Cameron Bailey wrote about the legacy of Jennifer’s work shortly after her death. His description of Jennifer — a framing her husband fervently agrees with — was that of a filmmaker and artist who embodied a “Black humanist agenda.”

When Bailey first learned about Jennifer’s cancer diagnosis in 1988, he joined a small group of Black creatives and organizers in Toronto to find ways to commemorate her work. This convening of local Black filmmakers, producers and writers took place at the Euclid Theatre, which is now a coffee shop. It was the first of its kind.

“We realized that there wasn’t any kind of organized group of Black people concerning film that existed,” Bailey explains. “We decided that we wanted to keep going and make it more permanent.”

As it turned out, this gathering in honour of Jennifer was the genesis of the Black Film and Video Network (BFVN). Formed in 1988, the network served as a training, advocacy and lobby group for Black-Canadian professionals in film and television. During the ‘90s, it’s also where Claire Prieto-Fuller mentored Black filmmakers who were making waves in the industry at large.

BREAKTHROUGH

AND BFVN

After the release of Prieto-Fuller’s Some Black Women in 1975, Black cinema in Canada was limited to documentary and short films — but never feature-length films — for the 20 years that followed.

That’s until a breakthrough in 1995, with the release of Clement Virgo’s Rude, a feature film about what it’s like to grow up in Regent Park (Virgo later directed episodes for major American TV series, including The Wire). Then came Stephen William’s Soul Survivor in 1995, and Christene Browne’s semi-autobiographical work, Another Planet, in 1999 (Browne was the first Black woman to write, produce and direct a feature film in Canada).

Rude was the first Canadian dramatic feature to be written, produced and directed by an all-Black team; it was directed and written by Clement Virgo, produced by Karen King, and featured actors Sharon Lewis and Maurice Dean Wint. Set in Regent Park and narrated by a neighbourhood DJ, the film focuses on the stories of three young Black Canadians: a drug dealer trying to reset his life, a homophobic and closeted boxer, and a woman who wants an abortion.

“Rude came out of a time where there was a resurgence of Black cinema in the United States, United Kingdom, Africa and the Caribbean,” Virgo says. “It was sparked by a kind of Afrocentricity that was happening at the [turn of] the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. It was happening in music and film — a more kind of consciousness around the Black experience.”

For Virgo, this includes a new wave of Black producers, such as John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood (1991), Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992), Isaac Julien’s Young Soul Rebels (1991) and Ngozi Onwurah’s Welcome II the Terror Dome (1995).

“Rude was within that context,” he explains. “I wanted to make something that felt unique to my experience [as someone who grew up in Regent Park], and to bring a very culturally specific movie to the screen. I wanted Rude to reflect the Black-Canadian experience as I knew it, and find an audience that would identify and see themselves in our film.”

While Virgo was working on Rude, Black cinema was beginning to blossom in Canada. The BFVN was in full force during the ‘90s with founding president Prieto-Fuller leading the way as a mentor. “The Black Film and Video Network were a kind of collective of filmmakers, like myself, and was headed by Claire Prieto-Fuller. She was like our den mother — our kind of leader. At that time, there weren't a lot of fiction films being made,” he says.

Outside of the penthouse meeting room where members of the Black Film and Video Network gathered, Claire Prieto-Fuller looks over the rooftop garden.

Alongside Virgo, many filmmakers and critics came up through the network, including TIFF CEO Bailey and filmmakers Karen King and Sudz Sutherland.

“Of course, one thing leads to another,” Prieto-Fuller says about the formation of BFVN. “I was working on [the 1989 film] Older, Stronger, Wiser. And we're always looking for Black women to work with.

“While we were doing that, we also did some research on where the other Black people [in the industry were] and what films have been made about this group of people. And where are those people in terms of who's going into film or television? Who's doing that?”

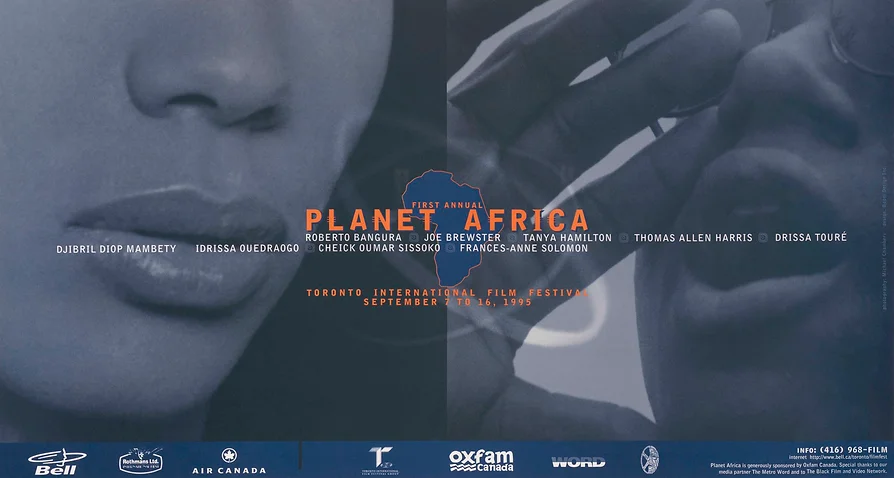

In mid-1990s Toronto, as Black cinema made waves around the world, Bailey — then a film critic working at TIFF — decided to reflect the times with a new program and party. After returning from his first trip to Africa, he launched Planet Africa, a new festival program that highlighted films from Africa and its diasporic communities through screenings, panels, press conferences and the famous Planet Africa Party.

POSTER PROMOTING TIFF'S PLANET AFRICA FESTIVAL PROGRAM IN ITS INAUGURAL YEAR.

Planet Africa ran under the TIFF banner for nearly a decade, between 1995 and 2004, programming works by Black diasporic filmmakers. In its year-one marketing materials, Planet Africa announced that its focus would go beyond the continent’s borders. That’s why films shown in 1995 included works by African filmmakers Idrissa Ouédraogo, Cheick Oumar Sissoko, Djibril Diop Mambéty and Drissa Touré, alongside the United Kingdom’s Frances-Anne Solomon and Roberto Bangura, as well as Joe Brewster, Tanya Hamilton and Thomas Allen Harris from the United States.

Orla Garriques, who oversees the Planet Africa Legacy project and previously served as an assistant programmer, says it was a proactive representation of the power of Black media. The program, she adds, provided a platform to celebrate Black-Canadian cinema at an international level.

“Planet Africa parties were so alive,” Garriques says from the garden of her home. “The success of it was because I think it came from the community, so the first party was not sponsored by TIFF money, the BFVN and patrons. The black promoters really got the word out.”

But the popularity of Planet Africa parties sometimes overshadowed the programming itself, according to Garriques. “The idea was the party was going to drive eyeballs to go see the films — it never happened and it’s very disappointing.”

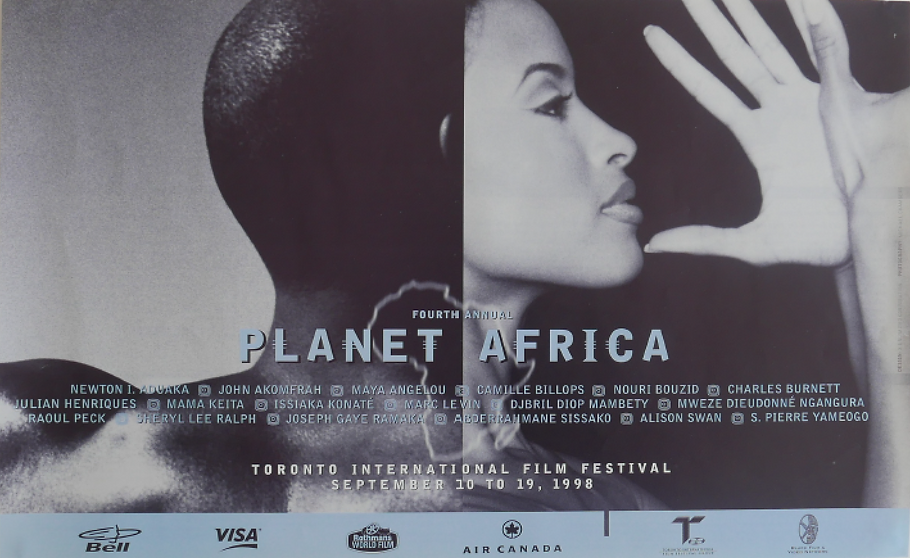

POSTER PROMOTING TIFF'S PLANET AFRICA FESTIVAL PROGRAM IN ITS FOURTH YEAR.

For his part, Bailey eventually learned that many Black filmmakers had complicated feelings about the program.

“Planet Africa began to dissolve because the most prominent filmmakers that we wanted no longer wanted to be in that section,” he explains. “I've had many long conversations with people — like John Akomfrah and Raoul Peck — who would say, ‘It feels like we're being ghettoized. We don't want to be in a section that's defined by our racial identity or our geographical location. We want to be in the Toronto Film Festival,’ which I understood.”

Bailey adds that people often tell him that what they loved most about Planet Africa was the party, which he has “mixed feelings” about, given the lack of traction for the program’s films. Still, he recognizes that the party was important for the community. “The party was this incredible communal space — a space of celebration where we could be our Black selves, do what we do, commune together, dance and celebrate Black music. That is all Black cultural expression, as well,” he says.

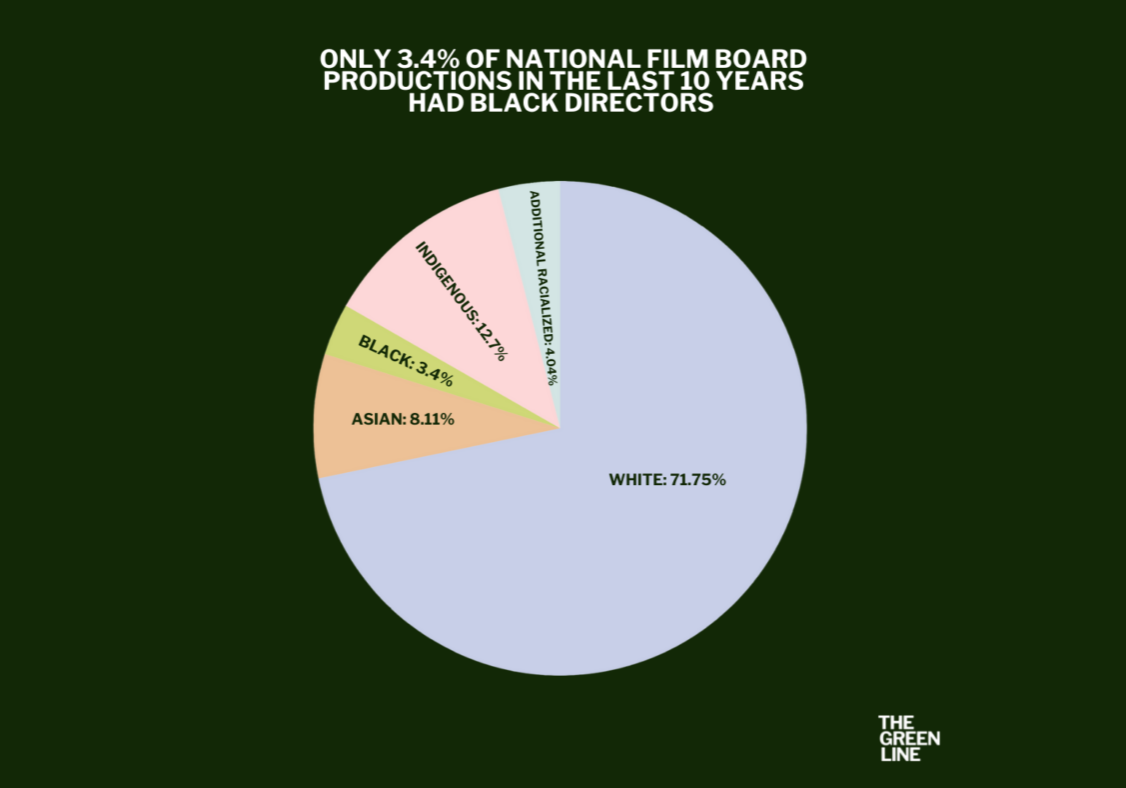

According to the "Racial Equity Audit of NFB Productions from 2012 - 2021," only 23 of the 676 movies produced during that time were directed by Black people.

BRAIN DRAIN

Pinpointing the exact beginning of Canada’s Black film canon is difficult, as there are differing origin stories.

Although many experts cite the films of Prieto-Fuller and McTair as a significant starting point, others emphasize the contributions of William Greaves. An American filmmaker who relocated from Harlem, New York, Greaves worked at the National Film Board of Canada in the 1950s, blazing a trail for other Black filmmakers. Regardless, the film canon includes significant works by our country’s many Black diasporas. They range from narratives focused on Black-Canadian history, such as the work of documentary filmmaker Sylvia Hamilton and Oscar-nominated director Hubert Davis, to narratives of Blackness more broadly, such as the work of Hodge de Silva, Virgo, Browne and Charles Officer.

But Canada’s systemic lack of support for Black-produced film and television is rooted in a lack of investment in Black stories and audiences. In July 2020, 75 Black-Canadian entertainment professionals — including Virgo, Officer and Jennifer Holness — signed an open letter to former federal Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault to address “systemically racist policies” that drove so many to the U.S. to get support for their careers.

“At every level, systems are in place to under-finance and under-support our projects,” the open letter says. “We believe this is largely because the systemically racist policies governing our industry leave Black writers, showrunners, directors and producers unable to make a decent living in this country.

“We should not have to move to the U.S. to make a basic living.”

In response to this “racial reckoning,” Telefilm Canada, one of the primary national film funders, committed an annual fund of $100,000 to the Black Screen Office, a project started by filmmakers Officer, Virgo, and Sutherland to create more job opportunities for Black creators and talent in Canada’s entertainment industry.

In recent years, there’s been an uptick of Black-Canadian productions on screen. Created by award-winning screenwriter Amanda Parris, the 2022 TV series Revenge of the Black Best Friend was widely embraced by the industry, as was the 2021 special miniseries 21 Black Futures. Recent Black-focused documentaries have also been recognized with industry awards. Yasmine Mathurin’s 2021 film One of Ours, which explores Black and Indigenous solidarities, received three CSA nominations last year, and Ngardy Conteh George’s 2019 doc Mr. Jane and Finch won two CSAs in 2020. Meanwhile, Officer’s 2020 drama Akilla’s Escape received eight nominations and won five CSAs in 2021.

Still, for Ian Kamau, Toronto lacks the foundation to support and elevate its Black artists. After decades of working with various community organizers and funders, Kamau believes solutions are hard to come by.

”There's really no infrastructure here — certainly not for Black people,” he says. “If you don't value the talented people in your city, they'll leave — and they should. That's capitalism 101: You go where you're valued. And that's why most of the artists go to the United States — because they have to. That's where the infrastructure is.”

“Toronto actually has one of the lowest per capita art-spending budgets of any city in this country,” Kamau adds. Indeed, in 2009, Montreal invested $55 per capita in arts funding that’s continued to rise since then, whereas Toronto had $19 per capita at the time. Nearly a decade later, 2018 records show that our city has only increased that slightly to $25 per capita.

Photos from a family album of Ian Kamau as a boy (pictured left) and Roger McTair and Claire Prieto-Fuller as young filmmakers (pictured right).

Despite these limitations, TIFF CEO Bailey says both Claire Preito-Fuller and Jennifer Hodge de Silva contributed something special and unique to the Black-Canadian film canon that’s shaped the industry as it is today.

“Jennifer’s history was part of a fairly small Black-Canadian-born community who grew up in Canada. But her most acclaimed film is Home Feeling, which was very much about the Caribbean Black migrant community in Toronto,” he excitedly explains. “Whereas Claire, having come from the Caribbean, was making films about Black-Canadian identity…There was this kind of crossing that was going on.

“The one who was born in Canada was interested in immigrant communities, and vice versa. I thought that was interesting. It was part of the mix of what being a Black Canadian meant at the time.”

Here's your chance to support the only independent, hyperlocal news outlet dedicated to serving gen Zs, millennials and other underserved communities in Toronto. Donate now to support The Green Line.

PART 3

toronto BLACK FILMMAKERS SCREENING

A community event and Story Circle hosted by The Green Line

About the Event

Despite its extensive artistic roots, Black cinema in Canada hasn't had the same kind of institutional support that it's enjoyed in America. A lack of investment in Black-produced television and film is one reason why. That's why The Green Line is inviting action-oriented community members like you to brainstorm brainstorm local solutions that combat systemic barriers to Black filmmakers and other creatives in Toronto. RSVP now for our in-person event.

Events are an essential part of our Action Journey. We want to empower Torontonians to take action on the issues they learn about in The Green Line — so what better way to do that than by bringing people together? From community members to industry leaders, anyone in Toronto who’s invested in discussing and solving the problems explored in our features is invited to attend. All ages are welcome unless otherwise indicated. Our only guidelines? Be present. Listen. Be kind and courteous. Respect everyone’s privacy. Hate speech and bullying are absolutely not tolerated. At the end of the day, if you had fun and feel inspired after our events, then The Green Line team will have accomplished what we set out to do. Any questions? Contact Us.

ANTHONY Q.

FARRELL

Anthony Q. Farrell is an award-winning writer, producer and director based in Toronto. He's written for The Office and The Thundermans, and has presided as executive story editor for Little Mosque on the Prairie. In addition, he's produced and performed in various stand-up and sketch comedies. Anthony is also the creator of original sitcoms Shelves, Overlord and the Underwoods, and Secret Life of Boys. He was honoured as Showrunner of the Year at the Writers Guild of Canada Awards in 2022, after receiving the same title from Playback in 2021.

DAWN

WILKINSON

Dawn Wilkinson is an award-winning filmmaker based in Los Angeles. A trailblazer, Dawn was the first Black-Canadian woman to break into dramatic series directing in Canadian Television. Her short experimental film Dandelions, iconic in black Canadian filmmaking, has screened at over 200 film festivals internationally and is often taught as course curriculum at schools across North America. Most recently, Dawn was the executive producing director for Step Up Season 3 for Lionsgate and Starz, and also directed the BET+ Original film Block Party. She's an alumnae of Norman Jewison’s Canadian Film Centre and the University of Toronto.

NOLA

COOKS

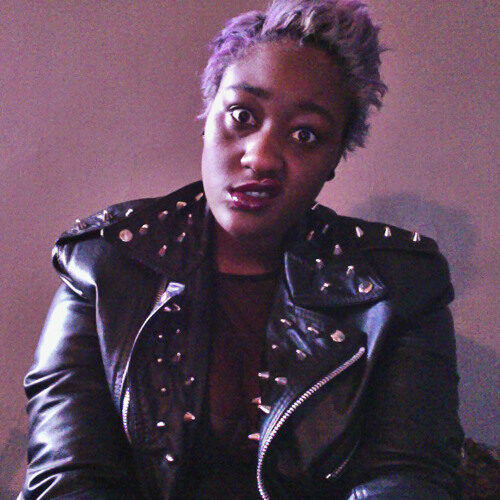

Nola Cooks started standup comedy at age 19 in Calgary, Alberta, where they immediately discovered they were hilarious. That motivated Nola to audition for Humber College's comedy writing and performance program, where they were ultimately accepted (proving that they are, in fact, hilarious). Nola won the Eugene Levy Comedy writing award for their 10-minute short play, All For Nothing. After spending several years at late-night open mics in Toronto, they decided to challenge themselves and apply their writing talents to film.

PART 4

Breaking Barriers for Black Filmmakers in Toronto

Event Overview

See what you missed

from our latest event.

Our community members brainstormed solutions for combatting barriers to Black filmmakers and other racialized creatives in Toronto.

Compiled by Alex Treadaway.

Panelists Dawn Wilkinson (left) and Anthony Farrell (right) discuss their experiences in the industry as Black filmmakers.

Host Tierra McKoy kicks off The Green Line's Black Filmmakers in Toronto screening and community event.

Our founder and editor-in-chief Anita Li discusses The Green Line's feature about the history and legacy of Black film in Toronto.

Local writer-director Dixon John asks the panellists a question at our Black Filmmakers in Toronto screening and community event.

SOLUTIONS

ACTIONS

Do something about the problems that

impact you and your communities.

Connect

and Network

BIPOC TV and Film aims to transform the Canadian screen industry by identifying and uprooting barriers to funding, training, and employment opportunities for Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour creatives at all levels — in front of and behind the camera, on sets and in all decision-making roles.

Kickstart

Your Project

The Black Screen Office (BSO) works to ensure a career in film is financially possible for Black Canadians, while advocating for an actively anti-racist approach in the industry. BSO offers a range of funding and professional development opportunities for Black filmmakers who are working as directors, producers, actors and writers.

Find an

Audience

Reelworld Screen Institute promotes films developed by Canadians who are Black, Indigenous, Asian, South Asian or people of colour. If you identify as someone from one of these backgrounds, submit your work to the annual Reelworld Film Festival, and sign up to attend its year-round events.

Join Our

Community

Continue the conversation with other Green Line community members.

Event attendees watch short film screenings at our Black Filmmakers in Toronto screening and community event.

Supporting The Green Line means supporting Toronto. Join our membership program today, so you can redefine our city as you see it.