PART 1

From Public Schools to Elite Prep: How Toronto’s Basketball Scene Became a Pay-to-Play Game

Jaiylen Ekanem, a student athlete at Uchenna Academy, competing in the 2024 Jane & Finch Classic basketball tournament.

AMANDA SERAPHINA JAMES RAJAKUMAR

Indian immigrant with a post-grad in journalism from Centennial College. Now living in Grange Park. Often has her four names confused as two different people, so it’s a pick-your-player situation.

October 7, 2024

We love cheering on our boys in red, black and white, so have you ever wondered where that talent comes from locally?

The Toronto Raptors’ 2019 NBA Championship was monumental for basketball fans across our city and country, and ever since, their fan base has only grown. Beyond being a victory for lovers of the game, it was a win for local athletes who could see a future for themselves in professional basketball.

But making it to the top doesn’t just take natural talent and rigorous training. You might need some extra cash.

Prep schools are now pumping out pro athletes, and have taken over Toronto’s basketball pipeline from public high schools — but at a higher cost. Some say they’ve made the sport inaccessible to aspiring players from lower-income families in the inner city.

TORONTONIANS GATHERED IN NATHAN PHILLIPS SQUARE TO CELEBRATE THE TORONTO RAPTORS WINNING THE 2019 NBA CHAMPIONSHIP.

So, how did we get here?

The Ontario Federation of School Athletic Associations (OFSAA), a federation of 18 regional school athletic associations, organizes championship tournaments for qualifying high schools across Ontario. Before prep school leagues and the Ontario Scholastic Basketball Association (OSBA) was born in May 2015, Toronto was all about basketball at public high schools. OFSAA’s tournaments produced stars such as Greg Francis and Andrew Wiggins, who grew up playing ball at public school, then entered bigger competitive fields like the NBA and Olympics.

Between 2012 and 2015, as prep schools started popping up in Toronto, competition in these tournaments became a one-sided match, with Crestwood Prep bagging the most medals. This led to OFSAA’s decision in 2021 to prohibit prep schools and players from competing in any of the federation’s championship games.

"At the high school level, everything is more volunteer-based. Whereas, with prep, it's more money-based because it's a business."

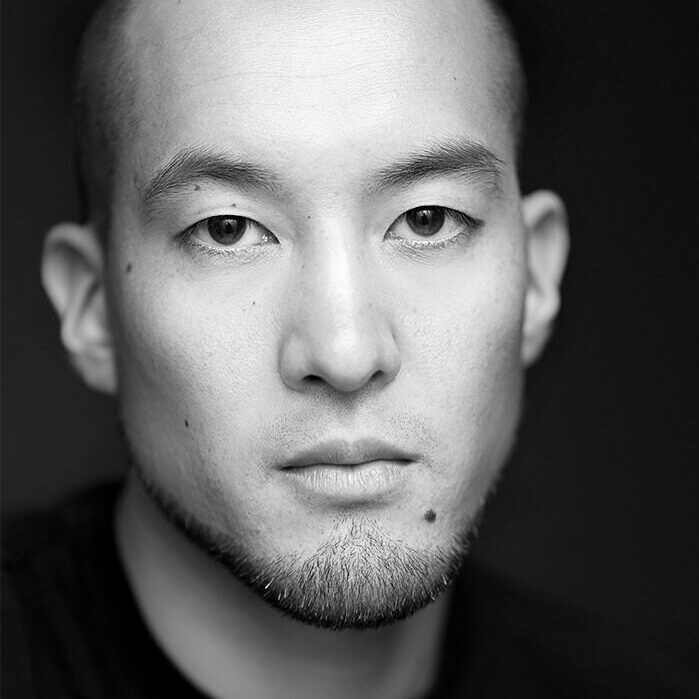

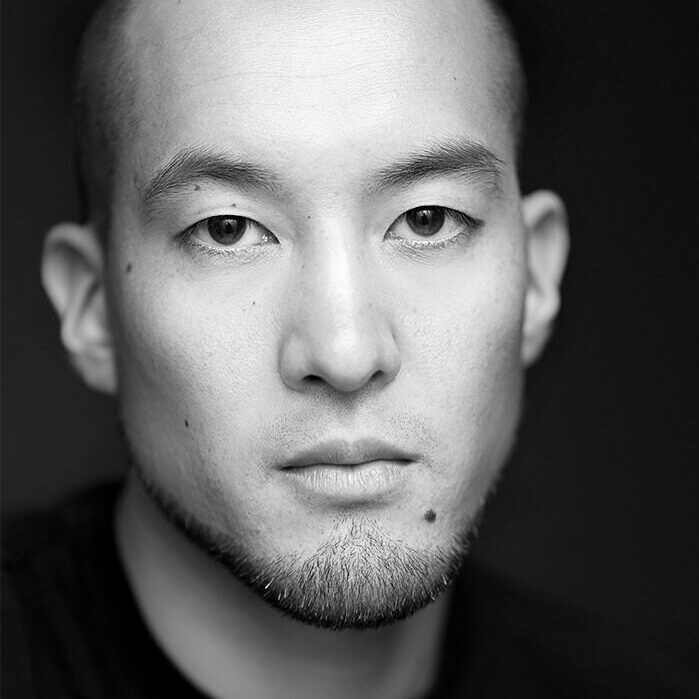

KAREEM GRIFFIN

FORMER COACH, EASTERN COMMERCE COLLEGIATE INSTITUTE

Kareem Griffin, former coach at Eastern Commerce Collegiate Institute, says that the growth of prep schools has pros and cons. Public schools used to be the only outlet for kids here to play basketball, but that caused many Canadian athletes to leave for American prep schools; so the introduction of prep schools in Toronto has helped keep talented players on home soil.

“The biggest issue of why high school basketball went the way that it was were labour disputes with teachers. That, I would say, was the main thing that transitioned from high school to prep because it became more of a business industry,” Griffin tells The Green Line.

“At the high school level, everything is more volunteer-based. Whereas, with prep, it's more money-based because it's a business. It's more looked at as a business as opposed to community initiatives.”

Kareem Griffin, former coach at Eastern Commerce Collegiate Institute, says that the growth of prep schools has pros and cons.

Take a look at the top-ranking high school basketball players in Ontario — most, if not all, go to prep schools. According to Next College Student Athlete, the world’s largest college athletic recruiting platform, only 3.4 per cent of basketball players at U.S. public high schools go on to compete in the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA). The NCAA organizes the largest college-level championships in the world, and helps athletes turn pro while still paying attention to their education.

Although Toronto has become a hotbed for basketball recruiters, Griffin says public high school events don’t attract high-profile recruiters, though they do attend prep events.

THE OAKWOOD COLLEGIATE INSTITUTE TEAM WON THE OFSAA BOYS' BASKETBALL CHAMPIONSHIP IN 2023 AND 2024.

Over the years, OFSAA’s model of “education through school sports” pales in comparison to prep schools, which offer more space, newer facilities, and better resources and training meant to build NBA stars — but at a higher cost than public high schools. They also attract international athletes and train them to be choice picks for the NBA. Over the last decade, Griffin says, prep schools have grown in number with at least 30 popping up across the GTA in that time.

“Basketball has turned into an upper-class, upper-middle-class sport. Lower-income families are unable to participate at the highest level like they did [before]. That's what high school provided for lower-income families being able to afford to play at a competitive level,” Griffin explains.

What’s more, athletes who participate in the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), which runs during the summertime, have the advantage of being recognized by recruiters year-round. But playing in these matches also carries a fee.

All of this means Toronto’s favourite sport isn’t easy to access for everyone, and big basketball dreams might just stay a dream for some.

“It's now up to the parents to market their athletes or their children to be seen by these bigger programs,” Griffin says.

Today’s stories lead to tomorrow’s solutions, so sign up for our newsletter to take action on the issues you learn about in The Green Line.

PART 2

From City Streets to Private Courts: The Changing Landscape of Toronto’s Basketball Dreams

TERU IKEDA

Freelance writer in an AI world. Shooting mid-range jumpers in 2024. Walking contradiction and aspiring basketball nerd.

October 14, 2024

Fans packed the CAA Centre in Brampton on July 25, 2024, as the Honey Badgers took the court in their final regular season game against the Vancouver Bandits.

In the 1994 seminal documentary Hoop Dreams, Arthur Agee, one of two main protagonists, treks through the Chicago snow at the crack of dawn.

As a high schooler, he commutes 90 minutes, one-way, to a predominantly white suburban school a world away to practice a city game.

When the documentary was released, Toronto did not yet have an NBA team. Thirty years later, much has changed. Toronto, no longer a basketball hinterland, earned an NBA championship in 2019, and has become a recruiting hotbed to fill coveted National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) and NBA roster spots.

In our city, there are plenty of Toronto Raptors fans, but the very scene that develops future NBA prospects is becoming inaccessible, reproducing some of the same divisions seen in Hoop Dreams. Elite basketball has sprawled out from the inner city to bigger facilities in the suburbs and beyond, where the cost to play a historically low barrier-to-entry sport is skyrocketing.

Kevin "Coach Mak" Jeffers smiles as he rallies together his regular group of players at the local Kings Courts sports complex in Oshawa on Sept. 4, 2024.

Meet Coach Mak

Kevin Jeffers, better known as “Coach Mak” of the championship-winning Central Technical School’s basketball team in Harbord Village, has always wanted to keep the city game accessible to those in it.

As Jeffers riffs off the names of players from Central Tech, a common thread emerged: None of them played in the NBA, nor were they professionals. Even in Toronto’s basketball scene, they weren’t famous names. That’s because Jeffers takes pride in his players being able to actualize a common basketball trope: using the game as a tool to improve one’s life.

The famed coach is no longer at Central Tech, a program he quickly catapulted to high school basketball success after his previous school, Eastern Commerce Collegiate Institute in Blake-Jones, was forced to shut down in 2015. Jeffers is currently coaching his son, Kenyon, in a basketball prep program called Full Circle Basketball Academy at Pine Ridge Secondary School in Pickering. But he laments being forced to step away from Central Tech.

“There’s a reason why we wanted to keep the program as is, is because it’s an incentive for the inner-city kids to stay home, inner-city kids to have a viable option that’s affordable,” he explains. “The talent is still there.”

A big reason behind Jeffers’ departure from Central Tech had to do with the repercussions of a 2021 Ontario Federation of School Athletic Associations (OFSAA) decision, which drew a firm line in the Ontario high school-basketball sand. OFSAA ruled that a player or school that participated in the prep school basketball circuit — that is, in the Ontario Scholastic Basketball Association (OSBA) or National Preparatory Association (NPA) — would be disqualified from OFSAA.

The term, prep basketball, confounds many, so here’s an explanation: Prep basketball refers to a program in which basketball becomes the primary focus of a student’s education. Whereas a private school’s main objective is to provide a general education, prep’s main focus is on the game. Some of these prep programs have their own facility, and schooling is either provided privately in-house or contracted out to a third party. In other cases, a program will attach itself to a public school, but operate independently; this is what Jeffers’ Central Tech team was forced to do after their 2021-22 season when they were no longer attached to the school.

OFSAA’s ruling adversely impacted programs like Central Tech. Before the separation, the team and its players were full members of the school, and had access to all its amenities (i.e. rooms for study hall, weight room, staff support, admin support, staff support during games) and the school collected fees and took care of all financial obligations.

But from 2022 and onward, the team (now called Toronto Prep) was independent, but still part of the student body and enrollment. Once school administration stepped back, the team had to compete for gym permits because it was no longer recognized as being part of the school. Players no longer had access to the same amenities they once had, and Jeffers, not the school, had to collect fees to fund his basketball program.

Competing in sanctioned tournaments down south became even more difficult, too, because under the new OFSAA rule, Toronto Prep was no longer recognized by its own state athletic association or equivalent whenever they competed in the U.S. With more doors closing on Central Tech, Jeffers had an even harder time recruiting players to put together a competitive OSBA team.

Central Tech was the last prep basketball team attached to a public high school in Toronto. Its sudden rise and disappearance from the prep scene was indicative of the rapid pace at which elite high school basketball has been moving out to bigger, private facilities in the inner suburbs and beyond. Simply put, Canada’s lone NBA city is struggling to retain its public-school origins.

A group of students from Uchenna Academy take to the court for practice after their session in the classroom on Sept. 17, 2024.

THE PRIVATIZATION OF HIGH SCHOOL BASKETBALL

Orangeville Prep is the birthplace of Canadian prep basketball, and the program quickly gained respect by initially recruiting Jamal Murray, who eventually captured an NBA championship, and Thon Maker, who went on to become an NBA player.

Orangeville Prep’s co-founders, Jesse Tipping and Aaron Hoffman, also partnered with Ontario Basketball Association (OBA) to create OSBA in 2015, the prep league that Orangeville and other Toronto prep schools would eventually play in.

As a member of OSBA and NPA Canada, St. Michael’s College School, a private school in Forest Hill, was early to join the prep basketball scene. Former coach Jeff Zownir, who now teaches in China, reflected on Ontario’s prep scene back in 2017.

“A number of these prep programs were not legitimate schools, but rather pop-ups bringing players together with non-legitimate schools,” he explains. “It seemed like this was not something we wanted to be a part of. It was more of an AAU league trying to be a legitimate high school league.”

AAU is an acronym for Amateur Athletic Union, which basically is club basketball during the summertime when there’s less red tape. Many AAU programs informally act as feeder programs into prep or private schools.

Central Tech’s disappearance from the prep basketball scene left a void within the city, but a new school has aimed to fill it. Managing director Dave McNee moved his private school, Uchenna Academy, into a 120-year old building in Dovercourt Village. He describes Uchenna as a “private school for public good,” and the only elite prep basketball program close to the downtown core. The multi-use building has two basketball courts and repurposed containers functioning as classrooms.

McNee says he started providing alternative education long before the explosion of prep basketball, and that his recent facility has been many years in the making. He combats the perception that Uchenna is a “fly-by-night” school — that is, travelling basketball teams that “pop up” a school to provide the veneer of a proper high school education.

Meanwhile, Oakwood Collegiate Institute, an inner-city public school in Regal Heights long known for its basketball program, is still competing for relevancy. Basketball writer and Oakwood graduate, Oren Weisfeld, says his alma mater has no plans of getting into the prep scene due to the high demands placed on coaches and players.

Oakwood’s gym is too small — there isn’t even enough space for corner three-point shots — but select players here are combating the self-fulfilling narrative that playing prep basketball is necessary to play at the collegiate or professional level.

“I stopped by there last season and it’s still kind of a vibe,” Weisfeld says, adding that Oakwood’s school spirit has remained the same. “I went into a game and it’s still pretty crowded.”

East of the downtown core, a private boarding school in Scarborough’s Agincourt North neighbourhood called Royal Crown Academic School has been winning the elite basketball-recruiting arms race. It now hosts one of Canada’s best basketball programs.

Uchenna Academy students warm up ahead of an intensive practice session on Sept. 17, 2024.

Schools like Royal Crown have the facility, personnel and reputation to bring top players from the outside in — all resources that public schools like Central Tech and startups like Uchenna wish they had. Peter Bandelj, who is from the same Slovenian capital as NBA superstar Luka Doncic, flew across the Atlantic to attend Royal Crown for one year. He was connected to the school through Jonathan Givony, a well-known NBA Draft analyst and founder of a scouting service called DraftExpress.

“He texted me after my U-18 European Championships, and congratulated me,” Bandelj says of Givony. “Then [he] asked me if I was interested in looking at options for prep schools in the States and Canada, and I said, ‘Sure, I’d be down.’”

Bandelj had competing offers from a U.S. prep school called Sunrise Christian, a pro team in Slovenia and Royal Crown. He ultimately decided to leave Ljubljana to continue his basketball development in Scarborough, a decision that’s paid off for both parties. After one year, Bandelj committed to a Division 1 program, Cal Poly, which means Royal Crown adds another alumnus to its long list of players who received D1 scholarships.

Bandelj is the prototypical sought-after recruit by GTA prep schools. International players like him are a near-finished “product” and they help continue to legitimize the Canadian-prep-to-NCAA pipeline narrative.

Kevin “Coach Mak” Jeffers keeps a watchful eye on his players, as they participate in their first set of drills, on Sept. 4, 2024.

THE PUBLIC PIPELINE

In contrast to Bandelj's decorated resume, Jamal “Lay Lay” Fuller had no college offers by his Grade 11 year.

He had ballooned to 280 pounds, but transferred from Westview Centennial Secondary School to Central Tech in 2018 to play under Jeffers.

“As a person, he just made me get out the Jane and Finch mentality that made me realize, you know, there’s more to it,” Fuller says, describing how Jeffers helped him mature. Jeffers is originally from Regent Park, and Fuller could relate to him. “He believed in me. [He was] in the gym with me every day, from Monday to Sunday.”

“It was never like a ‘no’ moment with him. He knows I want to work. He knew I was trying to get better. I told him where I wanted to be — I told him I wanted to get to [junior college] out of [Central Tech], having no offers. And, you know, he got it done. He made it happen. He stuck with me until I got there.”

Fuller recently committed to a Division 1 program after graduating from Hill College in Texas and going through the Division 2 gauntlet to get there. Orangeville Prep showed interest in Fuller as a high school student, but he believes good opportunities should be more accessible for players like him who come from an area of Toronto with one of the highest concentrations of youth (35 per cent of Jane and Finch is under 25 years old, compared to 27 per cent city-wide).

Unlike Arthur Agee in Hoop Dreams, Fuller chased his basketball dreams in his own backyard because it was still possible before the COVID-19 pandemic. Toronto is often associated with being an NCAA and NBA pipeline, but the pursuit of that dream is taking place further and further away from the city’s core due to the proliferation of prep basketball.

One of Kevin “Coach Mak” Jeffers’ players strolls towards the light during one of his practice sessions in Oshawa on Sept. 4, 2024.

“Basketball has become such a transactional business,” writer Weisfeld says. “There's a lot of people who are in it for the right reasons; there's also a lot of people who are in it for the wrong reasons, and then good people who truly believe that what they're selling is the truth when it's not the only truth.”

This self-fulfilling prophecy that prep school is the only ticket to the pros exists because coaches, players and families all feed into it. Even coaches like Jeffers, who are not primarily financially motivated, can now be lured by lucrative salaries to build programs at private schools across the GTA.

Jeffers jokingly admitted how there’s even less incentive to stay in Toronto’s core. “We've seen some job calls, and the amount that they're offering — you’re blown away. Like, what am I doing here?” he says with a laugh.

How Toronto is building a basketball dynasty with players who go pro while staying local

TERU IKEDA

Freelance writer in an AI world. Shooting mid-range jumpers in 2024. Walking contradiction and aspiring basketball nerd.

October 14, 2024

Brampton Honey Badgers guard Elijah Long drives towards the basket against the Vancouver Bandits on July 25, 2024 at the CAA Centre in Brampton.

Pro basketball player Elijah Mitrou-Long razzle dazzled over 2,000 fans on a late June Sunday night at the CAA Centre in Brampton, a GTA suburb credited with propelling the rise of basketball in Canada.

Mitrou-Long, a 27-year-old guard with the Brampton Honey Badgers, took over the second half to spearhead a dramatic comeback win against the Scarbrough Shooting Stars and hit the game-winning layup. His teammate David Walker, another guard, played a pivotal role in making the comeback possible.

“That game was lit. The experience playing with him was crazy!” Walker says, elongating his last word. “It was my first time ever watching [Mitrou-Long] play in person….He was just a good person to feed off his energy, and he taught me a lot, too, in the short time of him coming on the team.”

At 25 years old, Walker is only two years younger than Mitrou-Long, but the two represent two distinct eras in Toronto-area basketball. When Walker played high school and university basketball, our city’s basketball scene was established, whereas it was still fighting for legitimacy when Mitrou-Long was coming up.

Mitrou-Long left Mississauga to play U.S. prep and NCAA college basketball, and now returns home for the summers in between overseas pro contracts. Walker is from the North York neighbourhood of Maple Leaf, and graduated from Downsview Secondary, a Toronto public school, when Ontario’s prep scene was burgeoning. Like Long, Walker played NCAA basketball, but he decided to transfer back home to TMU because Toronto’s basketball scene now has enough resources to support his aspirations.

“If I could do the same thing over there over here, and get the same opportunity, might as well do it here,” Walker says, explaining why he transferred. “It’s my city, you know. So, might as well do it in my hometown.”

Brampton Honey Badgers guard David Walker defends the perimeter against the Vancouver Bandits on July 25, 2024 at the CAA Centre in Brampton.

THE CEBL'S RISE

Mitrou-Long and Walker both play in the Canadian Elite Basketball League (CEBL), which recently wrapped up its sixth season.

In Canada, a country where talent is developed locally at elite prep schools or in neighbourhood gyms but ultimately gets exported to the U.S. or overseas, the CEBL’s main goal is to develop Canadian players, coaches and executives. Aside from pro-am events during the summertime when professional players would come home, they never got to compete in a professional Canadian setting in front of family and friends.

The CEBL has changed that. Since its inaugural season in 2019, the league has intentionally differentiated itself from its precursor, the National Basketball League of Canada, to focus on developing domestic talent. For instance, Walker has played as a CEBL developmental player, a position reserved for a Canadian university or college student-athletes.

The league’s partnership with Canadian post-secondary schools not only allows student-athletes to test drive their pro basketball careers, but also network and learn from seasoned professionals. In 2023, Walker played for the Scarborough Shooting Stars alongside Anthony “Cat” Barber who he credits as an inspiration (Barber was a former McDonald’s All-American, one of the highest distinctions an American high school player can get). “Just watching him, seeing like — yeah, I could do the same thing he does. I just need the opportunity,” he says matter of factly.

Honey Badgers teammates Elijah Mitrou-Long (left) and David Walker (right) pose for a photo together after the conclusion of Brampton’s CEBL season on July 25, 2024.

Walker bounced around four different U.S. schools before coming home to attend TMU. He was recently a finalist for the CEBL Developmental Player of the Year award and confidently describes his plans to either play in the G League, the NBA’s minor league, or return to school. Playing and competing alongside an All-American and other pros has made Walker believe that he, too, belongs in the professional world.

Walker’s “I’m here now” self-assurance is a microcosm of what the CEBL aims to achieve, echoing Raptors president Masai Ujiri’s rallying cry to Torontonians to “believe in this city, believe in yourself.” Ujiri made the pledge to dispel Toronto’s self-fulfilling narrative that it wasn’t a desirable basketball destination.

Elijah Mitrou-Long (far right) and David Walker (far left) observe from the Honey Badgers’ bench during Brampton’s final regular season game against the Vancouver Bandits on July 25, 2024 at the CAA Centre in Brampton.

UNDERFUNDED BUT UNITED

Unlike Walker, whose rapid development is largely thanks to a formal network through the CEBL, Mitrou-Long relied more on his informal, close-knit group of friends who dub themselves “Wolfpack” or “WP.”

Mitrou-Long spent countless hours emulating his current skills trainer, long-time friend and the “core” of WP, David Tyndale, while playing at the Mississauga YMCA. “That’s my first mini-me. I see so much of me in him,” says Tyndale, 33, a former point guard at York University who made the Canadian All-Rookie team in 2009.

He attributes Mitrou-Long's passion and creativity to competing at the Y. “It comes from definitely growing up, playing a certain style of play, all of us being at that Mississauga YMCA, hooping and having to battle with different players,” Tyndale says.

But these weren’t any ordinary pick-up runs at the Y. Mitrou-Long's older brother, Naz, had a brief stint in the NBA. And the league’s favourite villain, Dillon Brooks, also played with Mitrou-Long. WP’s impact is so significant that Brooks has “W” permanently inked on his right shoulder and “P” on his left, which the world witnessed when Canada competed in the 2024 Paris Olympics.

WP’s success happened in spite of the lack of formal investment in their development. The combination of the Mississauga Y’s influence, a competitive basketball program at Father Michael Goetz Catholic Secondary School where several members attended and the fact that both these places were transit-accessible led to the unintentional birth of WP.

Relying on an informal community ecosystem for elite basketball development is highly vulnerable. A five-tower condominium development is currently scheduled to replace the YMCA. “It’s just how it goes,” says Tyndale. “It’s quite unfortunate….The YMCA was a major piece for our process because we didn’t have the access that is had [by other players] now.

City of Brampton policy planner Tristan Costa, whose master’s thesis evaluated the legacy of the 2015 Pan American and Para Pan American Games, sees the lack of investment into WP as symptomatic of a wider problem. “There’s this connotation around athletes coming from Canada not having the proper training or the proper facilities to conduct their training,” he explains.

Costa cites the residual benefits of Toronto hosting Pan Am, including the creation of the Toronto Pan Am Sports Centre in Scarborough, one of several multi-purpose sports facilities still being used locally. The Shooting Stars found a way to make use of the centre, which is co-owned by the City of Toronto and University of Toronto Scarborough. In its inaugural season in 2022, the Shooting Stars signed rapper J. Cole to play five games, two of which were at the Pan Am centre. This is an example of the kind of impact private businesses and public institutions can have when they work together to support and grow Toronto’s pro basketball ecosystem on our soil.

Jermaine “Rock” Anderson, Brampton Honey Badgers general manager and vice-president of basketball operations, keeps a watchful eye on his team from the sidelines during their final regular season game on July 25, 2024 at the CAA Centre in Brampton.

INVESTING ON AND OFF THE COURT

The CEBL has received even bigger fanfare among non-Ontario teams.

Winnipeg is set to host the championships next season and have received a $1 million investment from the Manitoba government to do so. And last summer, an All-Star Game featuring Scarborough’s Kyree Walker was organized in Quebec City’s Videotron Centre, and over 7,000 fans showed up to the TSN-televised game.

“We say that we’re basketball’s version of the CFL,” says CEBL deputy commissioner John Lashway, who helped launch the Raptors in 1995. “Western clubs do much better at the gate in terms of attendance than the eastern teams do. And there’s just so many more things competing for entertainment dollar and eyeballs than there are in most of the western markets.”

CEBL’s TSN deal last season was a “home run,” Lashway says, but the league is also focused on working with public partners to further the careers of homegrown basketball players. For example, the league has provided former pro players the opportunity to further their education and take on a different role in the industry. Both the Honey Badgers’ and Shooting Stars’ current general managers received fully subsidized M.B.A. education, thanks to Canada Basketball, the official governing organization for basketball in our country that’s funded by the federal government.

Jermaine “Rock” Anderson, the Honey Badgers’ general manager and vice-president of basketball operations, says his transition after retiring from pro basketball was seamless. He credits Lashway for believing in him to take on the role. “It's just being able to be fluid when things don't necessarily go as expected,” he says.

It’s these types of small wins that makes Lashway proud.

“We hit a lot of singles and doubles, to use a baseball analogy,” he explains. “And that’s really what you have to do…to build a sustainable league. When you see leagues go out and try to hit home runs, those are the leagues that fail.”

Earlier this year, the Shooting Stars unveiled plans to move into their own purpose-built facility right by Scarborough Town Centre. The timing of the proposed move coincides with the opening of the TTC’s Scarborough Subway Extension, which will mean more people will have access to their games. As a further boost to the Shooting Stars brand, co-owner Ibrahim made a $25-million donation to UTSC to build an entrepreneurship centre last year.

It’s a delicate dance when it comes to who pays for what, but the team got to this tipping point through public and private collaboration. Their shared goal? To build a strong basketball ecosystem in Scarborough, and Toronto, more broadly — one that’s resilient enough so that tomorrow’s Elijah Mitrou-Longs don’t have to solely rely on the strength of their packs.

Here's your chance to support the only independent, hyperlocal news outlet dedicated to serving gen Zs, millennials and other underserved communities in Toronto. Donate now to support The Green Line.

PART 3

5X5 YOUTH BASKETBALL TOURNAMENT

A tournament and Story Circle hosted by The Green Line and Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment (MLSE).

About the Event

The Green Line is partnering with MLSE to host a Story Circle and 5X5 basketball tournament for youth from ages 14 to 22 in the Garden District that’ll focus on supporting Toronto’s local basketball pipeline. We’ll also be brainstorming solutions to overcome barriers to underserved youth who might not have the resources to pursue professional basketball. Participating players will get a chance to win prizes from NuStep, and share their experiences as athletes in the city.

Complete and submit five waivers for each of your team members. If you're aged 0-17, submit this waiver; if you're aged 18+, submit this waiver). Then register your team now for this free event before spots fill up.

Events are an essential part of our Action Journey. We want to empower Torontonians to take action on the issues they learn about in The Green Line — so what better way to do that than by bringing people together? From community members to industry leaders, anyone in Toronto who’s invested in discussing and solving the problems explored in our features is invited to attend. All ages are welcome unless otherwise indicated. Our only guidelines? Be present. Listen. Be kind and courteous. Respect everyone’s privacy. Hate speech and bullying are absolutely not tolerated. At the end of the day, if you had fun and feel inspired after our events, then The Green Line team will have accomplished what we set out to do. Any questions? Contact Us.

PART 4

BASKETBALL FOR EVERYONE

Event Overview

See what you missed

from our latest event.

Our community members brainstormed solutions for improving the local basketball pipeline in Toronto.

Compiled by Amanda Seraphina.

Event attendees sit in a Story Circle at The Green Line’s October 2024 Action Journey about Toronto’s basketball pipeline. They shared barriers they’ve faced in playing the sport professionally and for fun, and also brainstormed possible solutions.

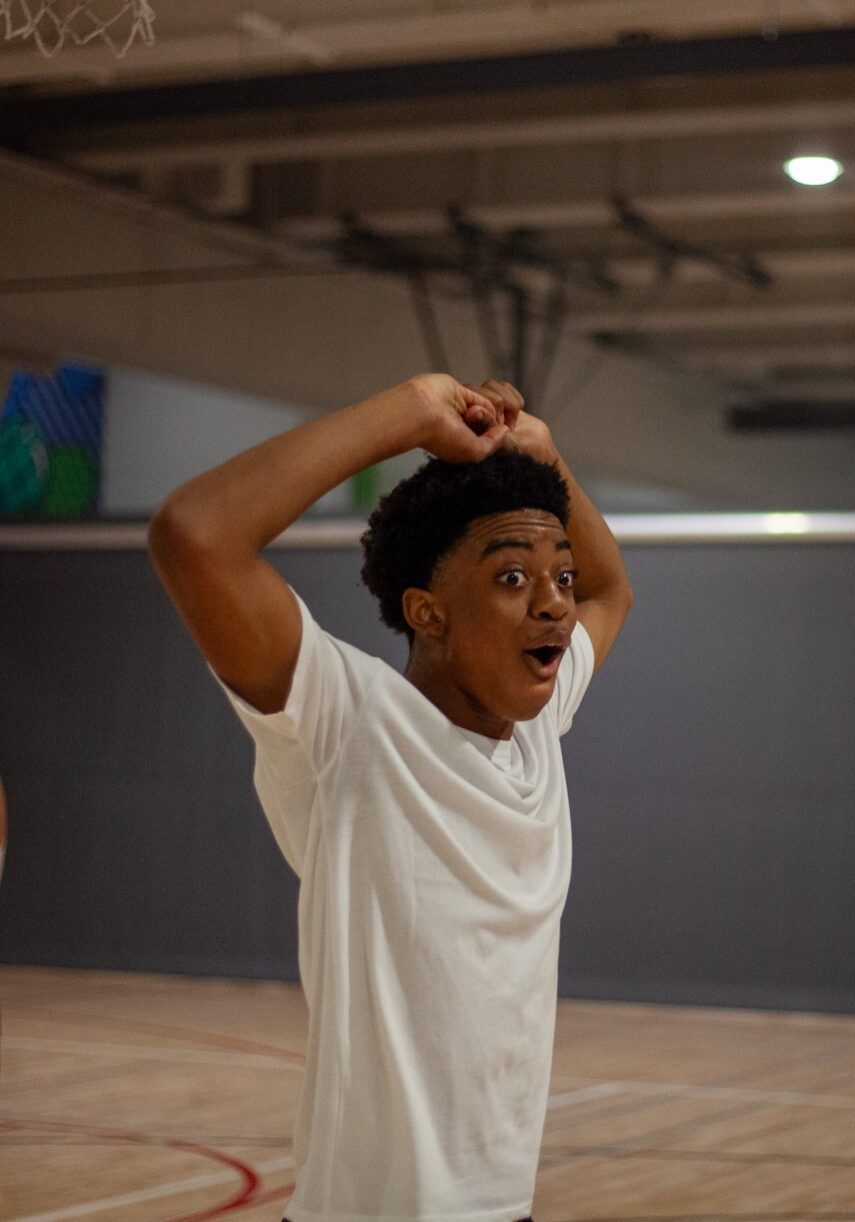

A player looks shocked at the end of a match during The Green Line’s 5x5 basketball tournament on Saturday, Oct. 19, 2024 at MLSE LaunchPad.

A player jumps to get a lay-up shot while his opponent tries to defend during The Green Line’s 5x5 basketball tournament on Saturday, Oct. 19, 2024 at MLSE LaunchPad.

Basketball players sit on the sidelines listening to their coach before their match begins at The Green Line’s local basketball pipeline Action Journey on Saturday, Oct. 19, 2024 at MLSE LaunchPad.

SOLUTIONS

ACTIONS

Do something about the problems that

impact you and your communities.

Find a schedule that fits

The City of Toronto has a list of community centres with drop-in basketball programs. The programs run at different times and for different ages.

Find your community

Need someone to play basketball with recreationally? Join pick-up basketball groups and find people near you who’d like to play.

Sign up for cost-free programs

MLSE Foundation offers “Ready to Rebound,” a no-cost basketball program for 8- to 14-year-olds and “Midnight Basketball,” a Friday night basketball program for 13- to 18-year-olds.

Join Our

Community

Continue the conversation with other Green Line community members.

Event attendees mingle with competing teams after The Green Line’s 5x5 basketball tournament on Saturday, Oct. 19, 2024 at MLSE LaunchPad.

Become a Green Liner to get exclusive access to our events and meet a community of people who want to rewrite Toronto's identity together.