THE GREEN LINE'S

Documenters Canada Field Guide

Welcome to Documenters!

Thanks for joining us! This guide will introduce you to the Documenters program and help you figure out how you can get involved. If you decide to take our training, you’ll find that this guide is a complement to that. Don’t hesitate to look back at this guide before you go cover a public meeting, or anytime if you feel you need to.

🖼️: SARA MIZANNOJEHDEHI FOR THE GREEN LINE.

Documenters at The Green Line is the first time a Documenters project is launching in Canada. But the project traces its roots back to Chicago in 2015. A group of journalists there founded City Bureau to produce news that was designed for and with communities.

In 2014, a Chicago police officer murdered 17-year-old Laquan Macdonald and protests erupted. Smart Chicago Collaborative, which had been experimenting with citizen storytelling, teamed up with City Bureau to document meetings of a new police accountability task force the city formed in response. The team at City Bureau discovered that having many people providing coverage of meetings could speed up the information collection process. They also found that it was easy to teach citizens how to document meetings and do research. And, they noticed that community members brought unique perspectives to their work. The documenting process displayed how community members could learn from each other and create a network of shared information, enabling collective power. A few years later, City Bureau launched Documenters to bring these learnings to communities across the U.S. The goal was to equip citizens like you to understand how to access and produce relevant information. As we write this field guide in May 2024, there are 19 Documenters branches across the U.S. and the number is steadily growing.

🖼️ : SARA MIZANNOJEHDEHI FOR THE GREEN LINE.

As a Documenter, you will attend public meetings of interest to Alexandra Park residents. You’ll document what happens at those meetings by making recordings and taking notes. These aren’t just a summary of what happened. They’re also an opportunity for you to offer context and focus on the issues that are most important to your community. For too long, journalists have been outsiders, looking into communities that they’re not part of. The goal of Documenters is to fix that problem.

We know that your unique perspective as a resident of your neighbourhood can help you figure out what information is most relevant to your community. Although you will not give your opinion in your notes, as a Documenter you will be able to pinpoint the most important points of conversation and decisions at these meetings, add context, and focus on the issues that most influence the daily life of Alexandra Park residents.

Documenting also means joining a group of citizens who are interested in their community and what happens in it. Program organizers will support you by creating an environment where you can learn, feel confident in your abilities and voice your questions. Together, we will build a network of information sharing where accountability thrives.

Your notes will be compiled in a document, edited by The Green Line and shared with the public.

🖼️ : SARA MIZANNOJEHDEHI FOR THE GREEN LINE.

These meetings are not typically covered by news organizations unless a major issue arises, but the discussions that occur in them often have a big impact on the lives of people in communities. If we aren’t aware of what is happening in our city or community, we can’t take action. Information is power.

🖼️ : SARA MIZANNOJEHDEHI FOR THE GREEN LINE.

At The Green Line and Documenters Canada, we know that citizens are not just passive recipients of information. As citizens, you have the power to be active in how the news is produced and find answers to questions while enabling people in your community to make it a better place.

For a long time, journalists have assumed that they know what information citizens may like or need. At The Green Line and Documenters, we want you to be part of that process: what do you want to know about your community, but cannot find the answer or solution to?

Our approach is grounded in community-centred journalism. Like The Green Line, Documenters in Alexandra Park produce information “for” and “with” community members, instead of “about” them. This focus enables us to create, engage in and nurture collaborative relationships in the community.

By sharing power and listening to each other, we can echo diverse perspectives, which is what we need to build power in our communities.

Above all, solutions matter to us even more than problems do. How can the media be less negative, anxiety-inducing and sensationalist? Solutions-focused stories made in collaboration with community members can help you feel more empowered to navigate Toronto’s problems.

We hope the work of Documenters will inspire community members to come together and look for solutions.

If you are curious about The Green Line’s approach to solutions journalism, read more about the Attention ↹ Action Journey.

This guide and this project owes many debts of gratitude to many people. This guide is inspired by the one produced by Documenters.org and the folks there have been especially helpful, in particular Max Resnick, who was endlessly generous with his time and sharing best practices as well as the outline of this guide. I’m also grateful to the staff at The Green Line, which served as the site of our pilot project for Documenters Canada; all the supportive folks at the Scadding Court Community Centre, which hosted The Green Line’s engagement outpost; Concordia University research assistants and MA students Clément Lechat and Sara Mizannojehdehi, who developed this guide and helped out in the process in countless ways; the entire fall 2023 class of Jour 605 at Concordia University, who initiated the community work to make this project happen; and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, which funded this pilot program.

The work behind this field guide occurred in a range of different places around Canada and the U.S. Many of these places, including Concordia University, are located on unceded Indigenous lands. At Concordia, we acknowledge that the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation is recognized as the custodians of the lands and waters on which we gather today. Tiohtià:ke/Montréal is historically known as a gathering place for many First Nations. Today, it is home to a diverse population of Indigenous and other peoples. We respect the continued connections with the past, present and future in our ongoing relationships with Indigenous and other peoples within the Montreal community. At The Green Line, we want to acknowledge that the land on which The Green Line operates is the traditional territory of many nations, including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples and is now home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples from across Turtle Island. We also acknowledge that Toronto is covered by Treaty 13 with the Mississaugas of the Credit. Our team is grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land.

🖼️ : SARA MIZANNOJEHDEHI FOR THE GREEN LINE.

Anita Li, founder of The Green Line: Documenters Canada, an initiative brought to Canada by The Green Line and Concordia University, aims to equip local Torontonians with the tools and knowledge to navigate and participate in local governance effectively. Documenters Canada supports The Green Line's mission to help young and underserved Torontonians thrive in a rapidly changing city by highlighting often-overlooked yet essential municipal meetings in Toronto, which ultimately better informs the public and empowers them to make change in their communities.

Magda Konieczna, associate professor of journalism at Concordia University: Living and teaching journalism in the U.S., I was familiar with the amazing work Documenters was doing, first in Chicago and then in a growing number of places around that country. When I moved back to Canada in 2021, I was surprised to discover just how much the crisis in journalism had deepened here. I started to think about how as a journalism professor I could work on this issue and I remembered Documenters. I knew that this program provided needed news and information in communities – but l was also inspired by the ways that it worked to engage, empower and equip people to get involved. As we discuss the crisis in news, we need to acknowledge that it’s increasingly journalists’ job is no longer limited to putting information out there, but includes helping community members see how they themselves can have an impact. This is what we hope to do through Documenters Canada.

This field guide represents our first attempt to create a Documenters project in Canada. It is a collaboration between The Green Line, a local newsroom in Toronto that is hiring, training and hosting the Documenters; and Concordia University, which is developing the materials. It is our hope that we can inspire other Documenters programs across the country.

🖼️ : SARA MIZANNOJEHDEHI FOR THE GREEN LINE.

This section was written with the support of Tamara Sabarini and Labib Chowdhury from Scadding Court Community Centre, and Mohsin Khattak and Kiley Fleming from Alexandra Park Community Centre.

Located in the Chinatown-Kensington neighbourhood, Alexandra Park is a tight-knit and rich community at a crossroads of many of the contemporary challenges facing Toronto. It has long been home to a diverse group of people from Canada and around the world. Today almost half of the residents are immigrants, making it among the most diverse places in the city.

Alexandra Park is equipped with a vibrant network of community organizations committed to improving your daily life. This includes two community centres – Scadding Court Community Centre and Alexandra Park Community Centre – the Sanderson Public Library and the Atkinson Housing Co-operative, which all contribute in their own way to shaping a more equitable neighbourhood.

Located right on the doorstep of downtown, Alexandra Park has been grappling with gentrification and rising housing prices. In Chinatown-Kensington, 70% of residents are renters and they are on average less wealthy than the rest of Toronto’s population. The neighbourhood is in the midst of a revitalization plan, one that will radically change the face of the community. The leaders that we spoke with were optimistic about the revitalization, noting that they were encouraged by the level of community involvement and the efforts made to avoid displacement, based on lessons learned from less effective revitalization projects in other neighbourhoods. In particular they pointed out that the involvement of the Atkinson Housing Co-op ensures that residents have a voice in this process.

While so much is happening in your neighbourhood, it receives little attention from the rest of the city. In a way, Alexandra Park can be described as a news desert: It has no local source of information to report on these transformations and receives little coverage from bigger media outlets. This situation is not unique to your neighbourhood — many other places in the GTA need more information that reflects their residents’ diverse realities and perspectives.

Over the years in Canada, media consolidation and newsroom layoffs have led to less hyperlocal news and more generic information.

At the same time, community leaders that we spoke with said that journalists come to the neighbourhood when something bad happens, but rarely report on the good things in the community. They pointed out that it’s possible to recognize the challenges facing the community while also focusing on its strengths and on how community members have worked to overcome the challenges. This gap is one that could be filled by your work as a Documenter.

However, residents are already working hard to make Alexandra Park a better place – and by getting involved in Documenters, you’re one of them! The neighbourhood is home to young Torontonians who are motivated to bring change. More than 56% of Chinatown-Kensington residents are between 15 and 44 years old.

The involvement of Documenters like you, scrutinizing public meetings and taking notes, will help improve accountability and make decisions more transparent.

Documenters will also help inform residents and community groups. Information is a powerful tool for communities to mobilize, fight back against unfair decisions and feel more empowered when looking for solutions.

We can also hope that this local initiative will build bridges in your community, foster trust and help you find ways forward to create common understanding and solutions.

PUBLIC MEETINGS

Why focus on public meetings?

Out of all the stories that are worth telling, Documenters chooses to focus on public meetings because we feel they are the purest form of local democracy at work. When public meetings successfully hear from and talk to citizens, they can have an amazing effect on local democracy by helping citizens create the kind of community they want to live in. But public meetings can also exclude and cause harm in communities. For instance, even if officials invite public participation, it can be hard for some people to participate because they don’t have time or don’t feel comfortable speaking in public. This can result in decisions being made that favour some parts of the community over others. For these reasons, Documenters focuses its energy on broadening participation in public meetings, while acknowledging that there are plenty of other events and issues worthy of documenting.

Government is supposed to work for us. For this reason, public officials are required to hold meetings where they talk about the work they’re doing and listen to residents. Sometimes they do this because they genuinely want you to know what they’re doing and because they really want to hear your input. Sometimes they do this because the law requires them to. Either way, it can be hard to follow what these groups are doing, because their agendas can be very detailed or hard to find and can use language that isn’t easy for regular people to understand.

Public meetings can be regularly scheduled meetings of officials who make decisions on the public’s behalf, such as the people we elect (mayor, councillors, school board representatives, etc.) and the people they appoint. Public meetings can also be one-off meetings on a particular topic, like a proposal to build something in a neighbourhood. These meetings are usually organized by elected or appointed officials who want to hear from the public about the issue or project. There can be one or multiple meetings, and they can focus on presenting information or hearing from the public. The information shared is meant to help the government decide what to do, but there isn’t really a way to guarantee that comments and opinions of citizens are taken into account. Meetings around issues or proposals can also be organized by community groups and these might be worth documenting, as well. These aren’t considered “public” meetings, because these groups don’t have a legal responsibility to represent the public.

The public meeting that gets the most attention in Toronto is Toronto City Council, where councillors meet with the mayor to discuss and make decisions about city-wide issues. City council has various committees that report to it, focusing on issues like housing, health and economics. Each community in Toronto has a local council called a Community Council. Alexandra Park is a part of the Toronto and East York Community Council.

The City of Toronto also conducts many of its services through agencies, corporations and boards, which also have public meetings.

To learn more about these groups, check out the appendix.

5-STEP GUIDE

This guide is a resource to help you document public meetings held by the local government and in your community.

You can use this five-step guide as a checklist to make sure you're ready before heading into a public meeting. The detailed instructions can help ensure that you take notes effectively and accurately.

- Double-check the meeting’s location and time.

- Bring with you what you are the most comfortable taking notes with (computer, audio recorder, phone, tablet, notebook, etc.). Be sure all devices are fully charged.

- Do a bit of pre-research to answer these questions:

- What is the meeting about?

- What is the agency/municipal body/institution hosting the meeting?

- Write up a short description before you go to your meeting. This will help you understand what the organization does.

- Who do you think might attend?

- See if you can find a list of elected officials or staff. Save this list, especially if it has photos, since it’ll help you figure out who’s who.

- What’s on the agenda? In particular, which issues on the agenda seem to be especially significant to your community?

- Before the meeting, make a list of 3-5 issues that you’d like to focus on.

- What if anything has been reported about this organization or issue in the past? You can search The Green Line’s site or the site of other news organizations you like, or use Google News to try to find past stories.

- It may be helpful to look at what happened at past meetings of the committee you’re attending, or check whether other committees have talked about some of the issues that you’re interested in. The city collects information on past meetings on this website. By clicking on a council, you can find its past, most recent, and future meetings. You can also read through meeting minutes, see what decisions were made, and watch a video recording, if there is one.

- You may want to review some of the basic rules around how meetings are run, called Robert’s Rules of Order – or at least have references on hand in case something happens that you don’t understand. The full list of Robert’s Rules is a whole book, but we like to reference simplified versions that will help you understand some of the terminology, like these two:

- Arrive early so that you can find a spot to sit, pick up on any pre-meeting buzz and possibly plug your recorder into the meeting’s sound system (see below).

Public meetings in Toronto are required to be open for anyone to attend. It is your right to record public meetings. You can do so as long as you are not disrupting the meeting. Under certain circumstances, meetings may be closed to the public, for instance when dealing with labour issues or personal information. However, no vote can happen during a closed session.

Learn more about when meetings or portions of meetings can be closed to the public.

This means that if anyone tells you you can’t be there, or that you can’t record, you should ask why. Feel free to share the information about open meetings from the city website and ask why this meeting is exempt to open meeting laws.

In case you are not able to record the meeting, or run into technical problems, no worries: Public meetings are usually broadcast live and available to listen to after the end of the meeting. Depending on the committee, it could take a long time before these are posted. And of course, you can miss the buzz and the vibe if you’re not in the room, so it is important to be present and alert during the meeting whenever possible.

- Start to record: Start by sitting as close to the front as possible – this will increase the likelihood that you’ll get a good recording. Turn on your recording device. It should be placed within a few inches of your subject’s mouth or a speaker/amplifier and on a stable surface. You may even be able to plug your recorder into the sound system at the meeting. Arrive early and look around for anyone who looks official (perhaps the clerk) who might be able to help you with this.

- Check your levels: Before the meeting starts, do what you can to figure out whether your recording is going to effectively capture sound from the meeting. This could mean putting it in its place, making a small recording and then playing it back to see if you’re able to hear it.

- Timestamp: When writing down your notes, write down times when something significant has been said. This will help you return to key moments when revising your notes. If your recorder is far from you, remember the time on the clock when you started your recorder and write down the key clock times, so you can find those moments later.

Start with our note-taking template to organize your notes.

At the meeting: What should I do?

- Start recording the meeting (audio or video, as appropriate).

- Take notes and add timestamps at important parts.

- Focus on gathering direct quotes, debate, decisions and details, like by-law numbers, names and titles.

- Focus on what is actually said, rather than describing how it was said, which could be misinterpreted. In other words, avoid noting that someone said something angrily, because that’s your interpretation of what happened. Of course, if it’s very dramatic and obvious, eg. someone starts crying, you can include that in your notes. And, if it seemed to you that someone looked angry or upset or happy or anything else, you can find them after the meeting and confirm those feelings.

- If something exciting is said, make sure you note the time and who said it so you can include the quote in your notes. If you’re going to include a direct quote, you will need to track the person down during or after the meeting to confirm their name and spelling.

If you have any questions while you’re on assignment, reach out to Anita Li, The Green Line editor-in-chief, at hello@thegreenline.to.

Follow-up interviews

You may want to do an interview before, during or after the meeting. Before you do that, think about why you are doing the interview. If someone said something interesting in the meeting and you’d like more information, that makes a lot of sense. If you have a follow-up question to something that happened at the meeting, think about who might be the right person to answer that question. Avoid asking a citizen about why city officials made a particular decision. You can ask the citizen for their opinion on that, but they won’t be able to explain the actions of the city officials. Similarly, don’t ask officials about how citizens feel about something — the citizens themselves should speak to that.

Once you’ve identified the right person to talk to and have tracked them down, start by identifying yourself. Say something like this:

"I am a resident of the City of Toronto working in the public interest to document civic events and meetings. My documentation is made publicly available in collaboration with The Green Line, a Toronto-based news organization.”

You’ll also want to make sure the interviewee knows why you are interviewing them and how you will use their answers. You could say a version of this:

“I would like to interview you because I’d like to know more about <fill in the blank>. I think your opinion will be insightful because <fill in the blank>. I’ll use the information that you share with me to help give my work context. Your quotations and name could be published through The Green Line’s work.”

In some cases, you might agree to use the person’s information off the record. That makes they’ll give you context, but they don’t want to be referred to in your notes. You should consider whether this is a reasonable request. Here are some things you could weigh:

- Why does the person not want their name used? Do they have a reasonable reason, e.g. they’re afraid of getting in trouble from their employer, or being retraumatized in connection to something bad they’ve experienced?

- Are they providing you with background information that you can verify separately?

- Are they criticizing someone or some decision? If so, they probably need to have their name included – otherwise, by being anonymous, they’re not being accountable to the person they’re criticizing.

- Are they offering you a tip that you can research elsewhere? If so, get as much information as you can so that you can run it by other people who will be willing to let you use their names.

If you’re unsure about whether it’s ok for someone to be off the record, get in touch with staff at The Green Line, who will help you think this through.

Start by transcribing your audio:

- Otter.ai is a great tool that can transcribe your audio for you.

Make your notes complete and accurate:

- Check facts such as

- Title names, pronouns, ages

- Dates

- Locations

- Making sure what someone said is true

- For instance if someone in a meeting refers to a past meeting or event, research what they referred to.

- Check your spelling.

- Listen back to the recording to get the exact words the person said and put quotation marks around them.

- Spell out any abbreviations.

- Include hyperlinks where needed for context.

Submit your notes:

- Submit your final notes to your editor in a Google Doc. Feel free to highlight anything you’re unsure about or need checked.

LEGAL ISSUES

Defamation law:

When you’re publishing something about someone, you need to be careful what you say about them. Think about how you would feel if someone said the same thing about you – would it hurt or embarrass you or make people think less of you? If so, it could be defamation and you could be sued. Canadian courts have concluded that a wide range of negative statements about someone may be defamatory, including any suggestion that someone is dishonest, immoral, a pedophile, a terrorist, a terrorist supporter, a racist, a human smuggler, a corrupt politician, or many other descriptions that are unfavourable or unflattering. Any of these could be a hint that the person is being defamed.

But, what if someone is a criminal, or is incompetent? Then, of course, you can include that in what you write and publish – but remember that it’s hard to conclusively prove that something is true. You can’t use anonymous sources or rumour for this. And it’s not enough that someone said it — it needs to actually be true. In other words, your statements need to be iron-clad.

One more thing: We have agreed as a society that public bodies can’t work properly if members are always worried about being sued for defamation. As a result, you can’t be sued if you report things said in a city council meeting or the meeting of a subcommittee, as long as you do so truthfully and without intending to harm the person you are writing about. This is also true when it comes to public documents, which include any matters of public record. Again, what you report needs to be an accurate representation of what’s in the document and you need to do it without malice.

Here’s an example: You’re at City Council. A police officer appears before council and says that the police are investigating whether the inhabitants of 1234 King St. are engaged in criminal activity. If you report this accurately and without intending harm to the residents of 1234 King St., then you cannot be sued for defamation, because it was said in a public meeting. But, you could get sued if it wasn’t said in a public meeting, if you reported it inaccurately, or if you intended harm. Here are some situations where you could get sued:

- The police officer says this in the hallway outside of the meeting and you report it. You’re only protected from being sued if you report what was said officially within the meeting, not informally outside of it.

- You report what the police officer said in the meeting, but you get it wrong (e.g. you write that the officer was talking about the residents of 1236 King St. rather than 1234 King St.).

- You report the alleged crime as truth, instead of reporting what the police officer said. This might sound like splitting hairs, but it’s important: you can say that the police officer told council that the police are investigating whether inhabitants of 1234 King St. are engaged in criminal activity. BUT, if you simply said that the inhabitants of 1234 King St. are engaged in criminal activity, you could be sued, because we don’t know if the crime is actually happening.

- You intend harm in your reporting. This is hard to prove of course. One example of proof of intended harm might be if you write an email saying, “We finally got them!” Be extra super careful about anything like this, even in your notes, file names, text messages to your friends, etc.

In truth, the best defense to being sued is to do a good job! These guidelines for how to do that are adapted from the book Media Law in Canada by Dean Jobb:

- Be skeptical. If someone tells you something that seems untrue, make sure you do a good job of checking it out.

- Be meticulous. Double-check your facts.

- Be restrained. Let people speak for themselves instead of adding your own voice. Always use the neutral word “said” instead of something that assumes someone’s emotion or intent eg. “exclaimed,” “shouted,” “declared.”

- Seek advice. Ask when you’re unsure.

Attending and recording public meetings

For the most part, city meetings are legally required to be public. In rare cases where the public is excluded from a meeting (usually described as an "in camera meeting"), there has to be legal justification for doing so. In Toronto, Section 190 of the City of Toronto Act (2006) lists the reasons a meeting might not be open. You don’t need to know the reasons, but they can be helpful to have on hand in case someone tells you you’re not allowed into a meeting. Some of the legitimate reasons for a meeting being “in camera” are:

- Receiving legal advice

- Security issues

- Buying or selling land

- Considering personal information about someone

- Labour issues or negotiations

- Anything to do with lawsuits or possible lawsuits

- Education or training of the members

- Any explicitly secret information that is shared with city officials

If someone tells you that you’re not allowed to be at a meeting, or not allowed to record at a meeting, you should ask why. Feel free to show them the above list (or the more complete one on the city’s webpage) and ask which of these situations applies. If you think you’re being kept out of a meeting that should be public, take good notes on what happened because you can work with The Green Line to file a complaint to the provincial ombudsman.

The Green Line doesn’t expect you to do research beyond attending the meeting. In some cases, however, you may want to do that so that you can check some facts or offer context on a situation. You can use two kinds of sources to do this: humans or documents. In both cases, you need to make sure the source you’re using is credible. Here’s how to check if a human source is credible:

- First of all, make sure you Google your source. When you do, it can be hard to tell what to believe, because there’s a lot of stuff on the internet. One way to approach this is to ask who wrote and published this information. Is it a source you trust, like the city or a news organization you’re familiar with? Another question to ask yourself is whether the person who created the information is the same as the person who posted it. There are lots of dubious sites out there that re-post things without fact-checking them, so see if you can figure that out. You can also use what you know about your neighbourhood as a gut check. Are there any immediate red flags about what the source says? Finally, ask yourself whether the source is reporting facts or opinions. Opinions can be valid too, of course, but it’s important to distinguish between the two. All this can be tricky to sort out! Staff at The Green Line are always available to help.

- What do you find out this way? Is there any information about their job? Any past public statements they’ve made, like things they’ve published online, or times they’ve been interviewed?

- Does it seem like this person is in a good position to answer your questions? What knowledge or background do you think they have that enables them to answer?

- Does this person have a vested interest in talking to you that might lead them to be misleading? Are they paid to comment on a particular issue, e.g. do they work for a political party? This doesn’t necessarily mean they’re not credible, but it’s important background for you to know when you decide whether or how to include them in your document. For instance, if you’re writing about a proposed development and the person you’re talking to works for the developer, you need to include that fact in what you write.

- Remember that you can ask a person what their connection is to the topic. You can say, “Why do you care about this issue?”

Here’s how to check if a document is credible:

- Just like with a human, you’ll want to do some background research. Who wrote the document and why? Were they interested in convincing someone of something, or is the document simply informative? As with a human, if the document is trying to convince, you can still refer to it – but you need to explain what you’ve learned about it. For instance, if you’re quoting from something written by the developer, or from a pro-development blog, you should explain that.

APPENDIX

Here's how you can better understand Toronto’s public meetings.

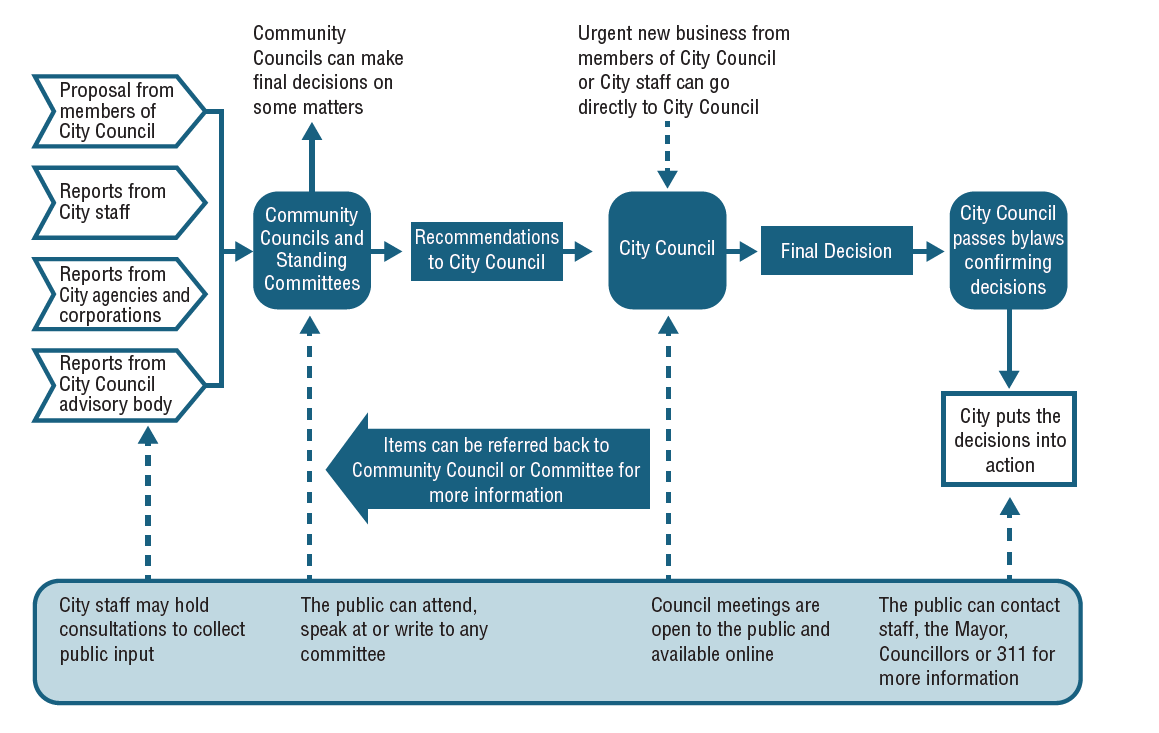

This appendix maps the different committees and boards that operate under Toronto City Council. It also explains council's decision-making process, lays out the differences between the three level of governments and outlines the available resources for different types of meetings.

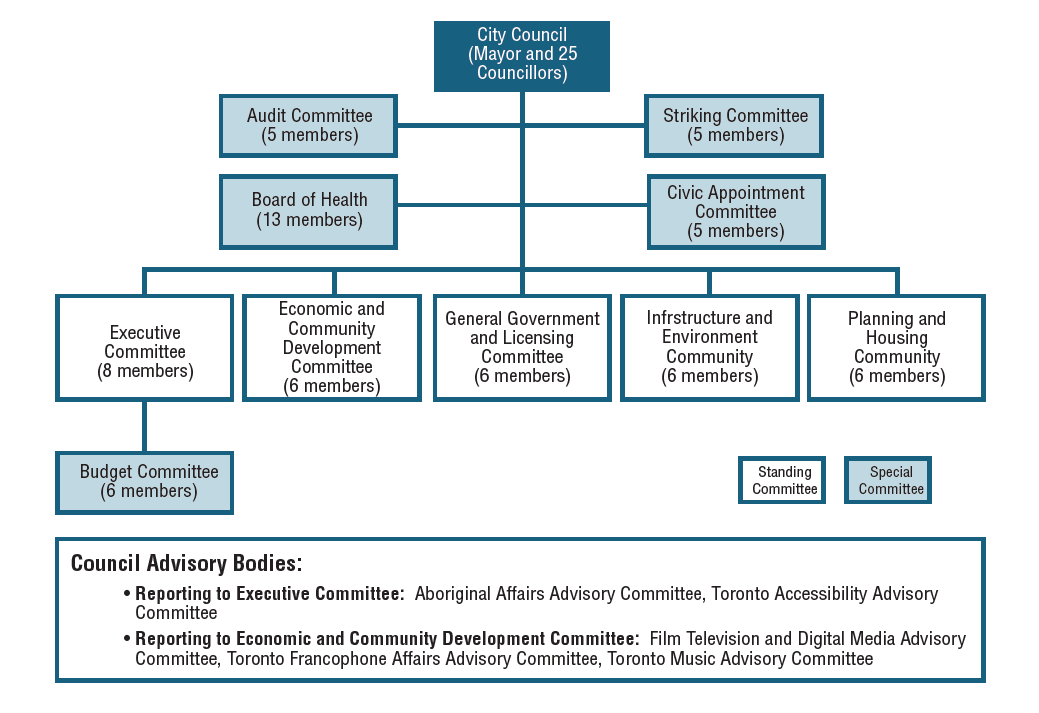

When thinking about how Toronto’s city government works, it might be best to look at a map:

📊: CITY OF TORONTO.

City council is made up of 25 councillors, each of whom represents an area of the city, and the mayor. City council meets in the last week of every month. The meeting is public, which means you can attend. But, the topics and speakers are pre-determined. Members of the public can’t speak at meetings of City Council, but they can speak at community councils and standing committee meetings. To speak at a meeting, you need to register online. – As a Documenter, though, your job is to, well, document. In this role, you won’t be speaking up at the meeting.

Along with sitting on City Council, the 25 councillors can also head or be a part of standing committees, special committees and community councils. Standing committees are permanent government bodies that make recommendations on a particular subject. The city has five standing committees:

- Executive Committee,

- Economic and Community Development Committee,

- General Government Committee,

- Infrastructure and Environment Committee and

- Planning and Housing Committee.

Community councils make recommendations on issues that are local to specific parts of town, like building development applications, tree removal and more. Here, some decisions can be made without the city council’s approval. There are four community councils, each representing a part of the Toronto region. If you are thinking about an issue that is specific to your area, like a beetle-infested tree or a road that may need a pedestrian crosswalk, this would be the place to go. The community councils are:

- Etobicoke York,

- North York,

- Toronto and East York and

- Scarborough.

There are also some special committees:

- Audit Committee,

- Board of Health,

- Budget Committee,

- Civic Appointments Committee and

- Striking Committee.

And a whole bunch of boards:

- Toronto District School Board,

- Toronto Public Library Board,

- Toronto Transit Commission,

- Toronto Police Service Board,

- Toronto Preservation Board,

- Toronto Parking Authority,

- Toronto Investment Board,

- Toronto Hydro,

- Toronto Atmospheric Fund Board,

- Board of Health and

- Film, Television and Digital Media Advisory Board.

Some City of Toronto services are offered through agencies and corporations that operate independently of the city. City councillors can be a part of them. These organizations can also bring forward recommendations covering things such as public health, the library, the waterfront, etc.

You can check out the full list of boards and committees here.

To get a recommendation considered at the Toronto City Council, it first needs to go through a standing committee, a community council or a board of and agency or a corporation. To voice your opinion on an issue, you can go to a community council and or a standing committee. There, councillors can recommend an issue to be heard at Toronto’s city council, where a decision can be made.

📊: CITY OF TORONTO.

You might be wondering what falls within the scope of the city, versus that of the province and country. The best way to think about it is by looking at what services are specific to each municipality versus what is shared between all provinces and territories. For example, the postal service is shared across the country, so the federal government oversees it. The legal drinking age is the same in Toronto and Ottawa, but different in Quebec, as the liquor control boards are specific to each province. The driver’s license system varies across provinces as well.

The City of Toronto Act states that Toronto’s municipal government covers: water treatment, parks, libraries, garbage collection, public transit, land use planning, traffic signals, police, paramedics, fire services, sewers, homeless shelters, childcare, recreation centres and more.

Of course, there can be some services that exist at municipal, provincial and federal levels. For example, there is the Toronto Police Service (TPS), Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), which is the Canada-wide police service.

If you look at this part of the city’s website, you’ll find information this about future, past or ongoing meetings:

- Agenda: What was planned to happen in the meeting. This will be updated once the meeting is over to reflect any changes.

- Decisions: After the meeting, the decisions reached by the council will be posted here. They may include additional information for context.

- Minutes: These are official notes taken by city staff. They aren’t as detailed or contextual as your work.

- Meeting Monitor: When it’s available, the "Meeting Monitor" allows you to monitor what is happening in a meeting in real time.

- Live webcast: Live streams of City Council events are available here.

- Video archive: A link to the meeting’s live recording on YouTube, if available.

TRAINING SESSIONS

The Green Line holds training sessions with community members who are interested in becoming Documenters.

In our first training, we look at different levels of government and how various City of Toronto boards and committees work. In our second training, we go over the logistics of documentation, watch a recorded public meeting and discuss it.

You can watch the recordings of these two trainings sessions in the videos, below.

Life in Toronto isn’t always easy — but you’re not alone. Twice a month, we’ll send you handpicked events that build real community, plus tips and local hacks to help you thrive in our city.