THE GREEN LINE

ORIGINAL STORY

How community networks build strong businesses — and even stronger neighbourhoods

The Green Line team learned about Black-led initiatives in Jane and Finch, dived into whether diverse entrepreneurship can benefit Toronto neighbourhoods, and explored different models of community development.

Olu Villasa, program manager at the Black Entrepreneurship Alliance, sits on the sidewalk in Jane and Finch.

MARY NEWMAN

British-Canadian journalist with a decade’s experience producing for the BBC and CBC. Hails from Robin Hood country so naturally hates wealth inequality and loves organized labour. Now resides in the dog paradise of Roncesvalles.

ANTHONY LIPPA-HARDY

Mississauga native currently studying journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University. Loves to explore different visual mediums to tell impactful stories that need to be seen.

Nov. 12, 2025

With files from James Westman.

This feature is part of our November Action Journey on inclusive entrepreneurship and innovation in Toronto, which was developed in partnership with Untitled Planning. The Green Line maintains full editorial independence to ensure journalistic integrity.

What are some effective ways to advance community economic and social development in racialized and low-income Toronto neighbourhoods?

Alexandra Lambropoulos, urban planner and co-founder of Untitled Planning, says entrepreneurship can foster social innovation and create solutions that come from within communities. “Diverse entrepreneurs tend to hire other diverse talent and build businesses that respond to challenges that others might miss,” she explains.

Lambropoulos adds that the resulting technologies or innovations can then be used to solve concrete problems that the community faces, such as food insecurity, transportation and climate change. She emphasizes that entrepreneurship creates conditions for other types of “community wealth building to occur, strengthening not just the local economy, but also the broader system as well.”

Prentiss Dantzler, University of Toronto sociology professor and founding director of the Housing Justice Lab, supports this idea that entrepreneurship isn’t just about the individual, but instead is a long-term investment into community. “For Black communities, it’s been a way to create opportunity where the overall system has closed doors. When folks start their own ventures, they’re not only generating income, they’re creating spaces that reflect our culture, our values and our sense of belonging,” he explains.

Dantzler adds that Black entrepreneurs also tend to reinvest in the community by providing mentorship to youth and sponsoring local events. “That kind of ownership builds pride and power. It pushes back against the idea that we’re just subjects of policy or development, showing that we can set the terms for our own futures.”

Olu Villasa, program manager at the Black Entrepreneurship Alliance (BEA), says entrepreneurship also has broader economic benefits. He says that encouraging more entrepreneurship creates a new tax base, contributes to the GDP and creates jobs for people who aren’t in the traditional workforce. “It shouldn't be about race. It's just good business,” he says.

For Lambropoulos, inclusive innovation and building strong economies happens through collaboration between government, the private sector and academia.

A board of program ideas at a community centre in Jane and Finch.

For example, the BEA was a co-designed initiative by the Black Creek Community Health Centre and York University. It also received funding from Canada’s Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario.

The BEA went on to create the first Black-focused entrepreneurship programming of its kind in Jane and Finch. The group is now planning and fundraising to build an innovation hub called The Element Centre, which it initially envisioned as an incubator and a community centre.

In researching the neighbourhood’s needs, the partners consulted community members who often brought up housing as a barrier that prevents them from entering or succeeding in entrepreneurship. So Villasa worked with Untitled Planning on a feasibility study to inform the design, operations and programming of The Element Centre.

As a result, integrating housing within the centre came up as a crucial support they’d like to offer. Villasa envisions a “sustainable ecosystem” to combat displacement while supporting entrepreneurs to innovate.

Beyond empowering local Black entrepreneurs, the centre aims to serve diverse groups, including young entrepreneurs, immigrants and previously incarcerated people, according to Sami Ferwati, co-founder of Untitled Planning. “The hub is rooted from the Black Entrepreneurship Alliance, but it's meant to support any marginalized group that is seeking to develop and grow economically, professionally,” he says.

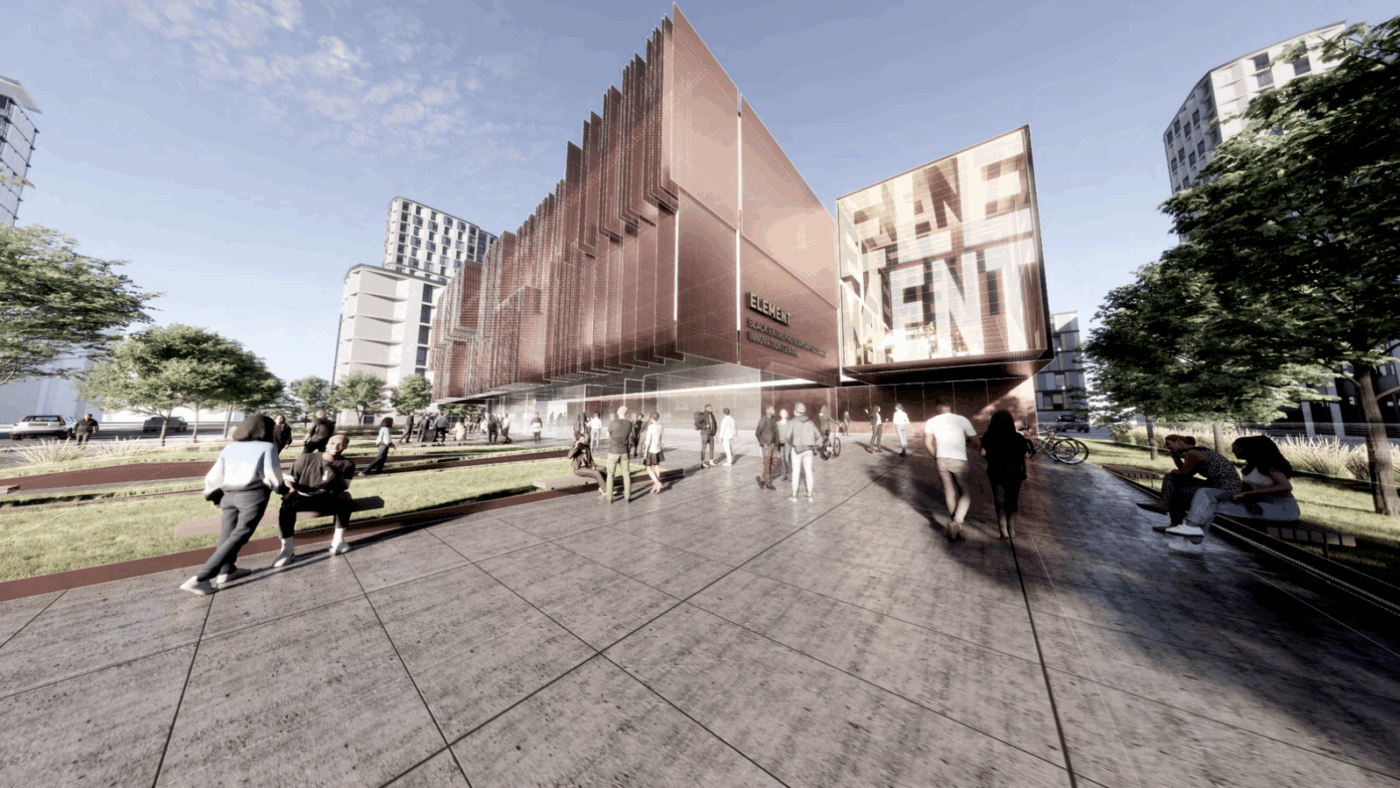

A render of what the Element Centre could look like.

🖼️: Black Entrepreneurship Alliance.

In northwest Toronto, other local organizations have also been providing wraparound services to ensure basic needs are met and community members are supported.

Bilqees Grant, an entrepreneur who grew up in Jane and Finch, says the Youth Association for Academics Athletics and Character Education or YAAACE, was instrumental in her entrepreneurship journey. “They were the people that I went to to understand how to be an athlete, but also how to ensure that I kept my grades up,” she says.

Grant went on to become a camp counselor with the organization and is now on the board of directors.

For Kwasi Adu-Poku, an entrepreneur and policy expert who also grew up in the neighbourhood, the Driftwood Community Recreation Centre, was an important resource. Adu-Poku says that when he was young, a knee injury impacted his mental health. But then, his brother encouraged him to get into basketball, and he started playing at Driftwood.

“[Basketball] is how I got to go to university. And as I started to face more adversity, I'd always circle back to the adversity I overcame to even play basketball,” he explains. “I found that was the guiding force that even got me in a place to start my own business.”

The Driftwood Community Centre in Jane and Finch.

MODELS IN OTHER NEIGHBOURHOODS

South of Jane and Finch, in another predominantly Black neighbourhood, the Little Jamaica Community Land Trust is supporting local entrepreneurs in its own ways. The land trust buys land and property on behalf of the community in order to keep rents affordable and protect locals against displacement.

“Our land trust has a non-negotiable commercial focus. So, when we're thinking about property acquisition, we're also thinking about commercial spaces, business owners and entrepreneurs that operate in those spaces,” says land trust coordinator Anyika Mark. “Businesses in Little Jamaica specifically aren’t just about product and sale….They're the cultural infrastructure for Caribbean identity to thrive and survive.”

The Little Jamaica Community Land Trust is now working with the BEA to implement a one-on-one business program to support local businesses owners. But Mark says more concrete support, such as funding to rent or buy commercial spaces and multiyear business grants, are needed from all levels of government.

In the south of Toronto, the Parkdale Centre for Innovation leads various programs including for women founders. And in Alexandra Park, Scadding Court Community Centre’s Market 707 helps newcomers start their own businesses with lower barriers for entry.

ALTERNATIVE MODELS TO ENTREPRENEURSHIP

But not all experts agree that entrepreneurship uplifts a broader community.

“Black entrepreneurship may empower a few Black individuals, but it doesn’t uplift the majority of economically dependent and exploited Black workers,” says York University politics professor Joe Pateman.

He argues that even when Black entrepreneurs gain access to capital, they still face competition from “more established, wealthier, white-controlled business,” which means they’re still dependent on “white-owned banks, suppliers and markets,” and are pressured to exploit low-wage Black workers.

According to Pateman, alternative models include worker co-operatives.

The Urbane Cyclist bike shop in Little Portugal and the Black-led Co-operative Cleaners of Ontario are examples of successful worker co-ops, where an enterprise is owned and run by its workers.

Pateman also identifies public housing and infrastructure, wealth redistribution and community control of industries that provide essential services, such as utilities and transportation, as models that can uplift communities. He adds that political mobilization of Black communities along socialist lines and in alliance with working-class movements, as seen with the Black Panthers Rainbow Coalition, is also an effective strategy.

“Real Black community uplift requires collective ownership and democratic control of resources — not Black entrepreneurship [or] Black capitalism,” he explains.

Fact-Check Yourself

Sources and

further reading

Don't take our word for it —

check our sources for yourself.