PART 1

Silent Struggle: The experiences of LGBTQIA2S+ Tradespeople

Elyse is a carpenter and landscaper who identifies as bisexual.

ADELE LUKUSA

Graduate of Toronto Metropolitan University and Kitchener native enamoured with Toronto. Lover of Jamila Woods. Currently working on supporting mutual aid efforts and unpacking the nuances of Black haircare.

July 1, 2024

Editor's note on names and ages in this feature: Names can be fraught for many people in LGBTQ2S+ communities, but especially trans and non-binary people. It's common for people to be using a name different than their legal name, to use one name only and no last name, to change their names, etc. In addition, queer tradespeople generally work in hostile environments, according to our sources. In this feature, we haven’t used any pseudonyms, but only a few sources have chosen to use their full legal first and last names, and provide their age due to concerns over privacy, harassment and doxxing.

If women in construction are facing a “cement ceiling” as our feature reporter Megan Kinch puts it, then LGBTQIA2S+ folks are facing a different but just as challenging barrier to success in the trades.

“I want to be a well-rounded carpenter and be allowed to do heavier tasks. But it's like I have to prove myself to do it,” Elyse*, a queer carpenter of colour shared with The Green Line. “Then it's a lot of pressure ‘cause if I fuck up anything everyone [cisgender, heterosexual men] is like, ‘I told you so!’’

Unlike their cisgender male counterparts, Elyse says they’ve often been underestimated and that their work hasn’t been taken seriously. To avoid dealing with the judgment and harassment normalized in trade work, Elyse has sought out solo or two-person jobs for their carpentry apprenticeship. Even when they proved themselves at work, Elyse often experienced “heckling and creepy comments.”

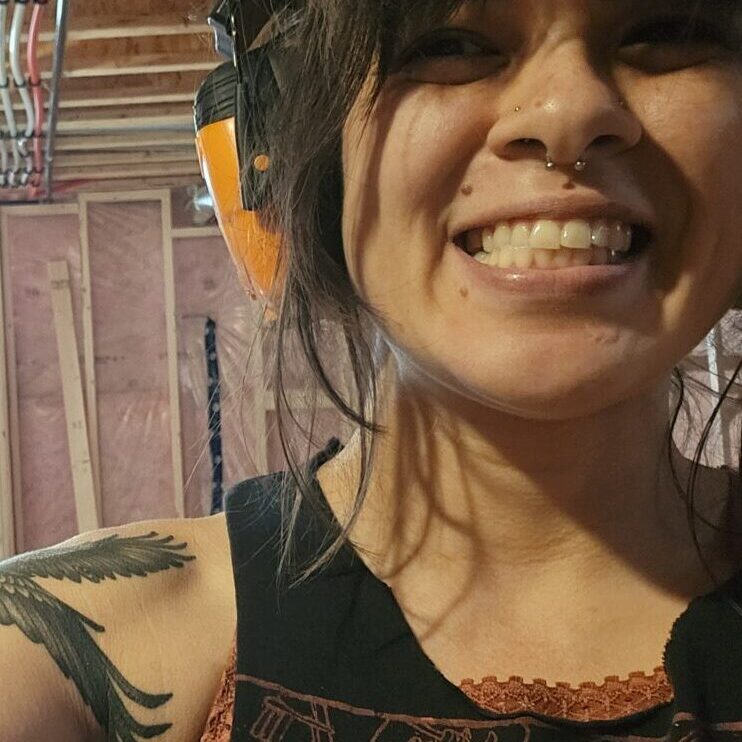

Dot S. is a trans woman who worked as an electrician in the 1970s.

Elyse's experience is common for queer and trans folks in the trades.

When you break down the workforce according to sexuality and gender, 93 per cent of tradespeople across Canada are heterosexual men, according to a study from the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC). Only 1.5 per cent of tradespeople surveyed identified as being part of LGBTQIA2S+ communities — that’s more than 600 tradespeople across Canada. Although this percentage may seem low, researchers noted that the actual number is likely higher due to underreporting. (Note that the survey used for the SRDC study only covered sexuality, and didn’t account for gender minorities. For example, no distinction was made between cis and trans tradespeople, so the latter were not counted.)

What’s more, only 2.1 per cent of employed Torontonians in 2023 work in construction, though the city is the core of the industry in Ontario, with around 30,000 construction workers making up nearly half of the province’s construction workforce.

"If you're not a straight white man and you're coming into construction, you're almost seen as a liability."

ANONYMOUS SOURCE

SOCIAL RESEARCH AND DEMONSTRATION CORPORATION (SRDC) STUDY

The lack of presence of LGBTQIA2S+ folks in blue-collar jobs such as construction makes more sense when you take barriers to access into consideration.

By and large, Canadians who identify as LGBTQIA2S+ are reporting higher rates of discrimination, verbal abuse, sexual harassment and job precarity, according to a study by the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto. The same study reports that queer men and women are three times more likely to face precarious employment compared to their straight counterparts, no matter the field.

Michelle is an electrician apprentice who identifies as a trans woman and lesbian.

Generally, their road to employment is often marred by prejudice, discrimination, heteronormativity, cisnormativity and constrained choices, according to Pride at Work Canada’s 2022 report. Visibly queer and trans job seekers find it hard to make it past the interviewing process, and receive lower pay compared to their cis and heterosexual counterparts. Once hired, queer and trans workers struggle with retaining their job long term, face misgendering or microaggressions from coworkers and clients. They also lack significant advancements or promotions.

Jonas Spring is a queer landscaper, as well as the owner and operator of Ecoman, a residential landscaping and gardening practice in Toronto.

The SRDC study on LGBTQIA2S+ workers in the trades echoes these broader systemic issues. It identified several core problems in the field, from unsupportive peers and management, to an absence of LGBTQIA2S+-specific resources.

“If you're not a straight white man and you're coming into construction, you're almost seen as a liability,” one of the anonymous interviewees of the SRDC’s study said. “You come in and you feel like you're coming into a hostile place already. You've already got to watch your back because of your identity. A lot of that just comes down to the fact that there are no policies and procedures already in place.”

Lenny Olin is a queer electrician.

Historically, organizers from the community themselves have done the work of advocating and creating resources for LGBTQIA2S+ workers.

As covered in Prabha Khosla’s Labour Pride: What Our Unions Have Done for Us, queer organizing that started in the ‘70s onwards often overlaps with labour activism. In 1973, after failing to get Toronto City Council members to support its anti-discrimination policy, Toronto’s chapter of the Gay Alliance Toward Equality (GATE) found solidarity with union CUPE Local 73. This act of solidarity helped other CUPE unions across provinces collaborate with local queer organizations to continue pushing progress for LGBTQIA2S+ human rights.

Today, queer workers in Toronto who work in all fields are protected by the Ontario Human Rights Commission, and are supported by organizations like Pride at Work Canada, but they’re still missing the tools to begin cracking that cement ceiling.

Editor's note: Most trades are in construction and manufacturing. Non-construction trades, especially hairdressing, are also intensely gendered in different ways. Non-construction or non-manufacturing Red Seal trades like bakers and cooks often face intense sexism and homophobia, but are beyond the scope of this particular journalism project. We also did not interview workers in the automotive repair trades. Our project generally had a focus on construction trades and landscaping, while also including manufacturing, and film and television trades and worksites.

Today’s stories lead to tomorrow’s solutions, so sign up for our newsletter to take action on the issues you learn about in The Green Line.

PART 2

Brick by Brick: The Fight for LGBTQIA2S+ Rights in Toronto's Trades Industry

MEGAN KINCH

Labour journalist and union electrician from Toronto. Most recently published in Briarpatch Magazine, West End Phoenix and Spacing. A resident of Kensington Market who enjoys playing weird music in the park late at night.

KAITLYN SMITH

Published author, national politics linguist and immigration reporter, and investigative data journalist living and reporting in Morningside, Treaty 13.

July 8, 2024

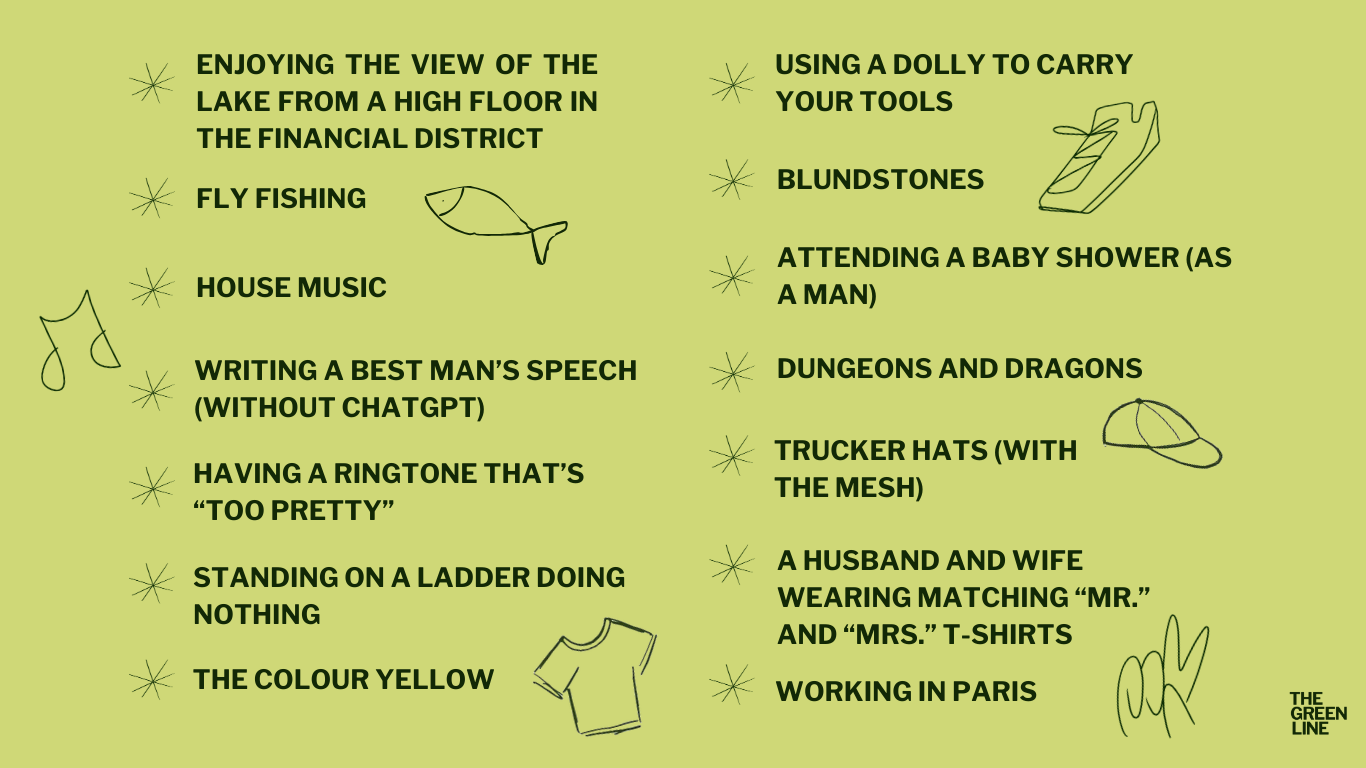

Peter Arrow is an electrician apprentice based in North York who identifies as bisexual.

Skilled trades jobs, especially in construction, occupy an interesting social and economic position in Canadian society as essential workers who are sometimes invisible.

Seventeen per cent of the labour force in Canada works in the skilled trades, yet the lives and experiences of trades workers are not well understood by the broader public. The experiences of queer and trans trade workers are even more opaque, given the lack of data, activism and reporting on LGBTQIA2S+ people in general.

Skilled trades jobs are intensely gendered, and trades spaces are often white, cis, heterosexual male spaces in which all other workers experience serious discrimination, according to the limited data available and Toronto-based sources who spoke to The Green Line. Many local queer tradespeople told us their work environments, as well as human resource practices and workplace safety, were like “being trapped in the 1970s.”

Here in Toronto, one of the world’s most diverse cities, we have the full alphabet spectrum of LGBTQIA2S+ — or 2SLGBTQQIPAA+ — with new letters and identities evolving in intersectionality with people’s other identities. But in the trades, this rainbow complexity confronts a workplace where physical violence is an ever-present reality; where the workplace sometimes feels more like the street corner, the subway, high school halls or a prison yard than a professional place of work; where production values, “shortage of work” layoffs and the ever-present calculus of safety versus making money quickly creates rough work environments.

Yet, construction and trades — seen as quintessentially homophobic — have always been spaces of queer reclamation and definition. Even back in the ‘70s, there were widespread queer archetypes related to the trades: the butch lesbian tradeswoman, the village people’s construction man, the tomboy, the rough trade working class lover and client of trans women.

People’s lives never fit did fit neatly into any of these archetypes, and with the flourishing of gender and sexual identities today, there are bois, non-binary they/thems, trans women, two-spirited people on construction sites — all the complexity of human life and sexuality that people no longer feel they have to hide, even at work, even in hostile trades spaces. Then we have those who are still hidden in the shadows: straight guys on Grindr, people who are out and proud in their personal lives but tactically closested at work. There’s no one LGBTQIA2S+ experience in trades, so all these identities play out differently at the worksite.

Queers started to gain legal rights back in 1969 when homosexuality was decriminalized in Canada. But that doesn’t mean the barriers are gone, 55 years later, particularly in the trades industry. For example, although women still make up just 1.1 per cent of many construction trades, queers are so few and far between that there are no industry advocacy organizations specifically focused on LGBTQIA2S+ issues, and minimal stats about their experiences.

“I have a lot of friends who have been in various trades industries, and then left because they felt uncomfortable...working with Bob who has been welding for 50 years, and doesn’t give a fuck about your pronouns,” says Castle*, a trans carpenter and owner of Three Dollar Bill, a queer bar in Parkdale.

Castle says there's a lack of recognition of queers in trades, along with a dearth of funding.

By the numbers

Aggregating data on the dangers and discrimination that queer and trans tradespeople face is challenging in an industry that simply does not want to know about it, and in a culture, according to our sources, that often ignores working class queer issues.

“The only reason I know they're queer is because they know I'm queer,” one respondent told researchers in a rare report about the sexual diversity of workers in Canada’s skilled trades force between 2007 and 2020.

Seventeen per cent of the labour force in Canada works in the skilled trades, and the vast majority — 93 per cent — are heterosexual men, according to a September 2023 report by the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC). In construction trades, the general statistic of 93 per cent heterosexual men is likely a much lower percentage than is actually in construction trades. Many stats that otherwise illustrate the lack of gender diversity in construction and manufacturing trades are often hidden by the inclusion of other types of trades that have more gender diversity, such as hairdressing and horticulture. What’s more, industry-wide construction data includes occupations far from the coalface that also have higher representation of women and diverse genders.

Women account for just 1.1 per cent of Canada’s workforce in construction trades, though the SRDC report found more lesbians (0.6 per cent) in the trades than straight (0.3 per cent) or bisexual women (0.2 per cent) combined (this report did not get numbers for trans, non-binary and other gender identities).

The report adds that most cis white men in trades (81 per cent) further exacerbate this disparity by refusing to check boxes about race or gender “because there is only one human race,” or sarcastically claiming “Jedi” as a religion in demographic surveys, which one of our reporters, Megan, has witnessed first-hand as a professional tradesperson. People we interviewed have also seen this happen on worksites, and have had to make tough decisions about whether or not to out themselves on surveys they then need to hand to a homophobic foreman or supervisor.

“One area that women have not been able to make headway — and [this] is for both queer and straight women — is the percentage of women in the trades has not really changed much since the ‘70s,” McMaster University labour studies professor Suzanne Mills says about the SRDC’s findings.

Despite accounting for around 1 per cent of workers in construction, according to the SRDC’s national findings — and regardless of their sexual orientation — women experience a range of harassment in trades and construction depending on how they present, and are often the target of homophobia by people who assume they are queer (even if they aren’t) because of their job, clothes or gender presentation. “A woman working in the trades, in itself, is a little bit queer,” Mills says, explaining that women in the industry, regardless of their sexual orientation, challenge the dominant culture of masculinity by working in an historically male field.

But the spectrum of harassment and violence fluctuates depending on whether a woman is perceived as “gay” or “not gay.” Whereas cis-appearing women are objectified by cat calls or dismissed as incompetent, lesbians — or anyone suspected to be one — challenge the dominant culture of masculinity simply by not dating men, according to Mills.

“Men usually assume I'm a lesbian, too, somehow,” says Elyse*, a carpenter and landscaper. “In a way, I'm kind of scared for them to learn that I'm bisexual ‘cause it maintains a better boundary if they think I just never fuck men.”

Although lesbian and bisexual women outnumber straight women in the trades, generally, there’s been a lack of recognition of queer identities in women in trades spaces. Recently, though, the SRDC says industry conversations have shifted to more often recognize heterosexual, bisexual and lesbian women, but less often trans, non-binary and gender-diverse tradespeople.

In fact, neither trans nor non-binary were available options in nationally distributed questionnaires by Statistics Canada until 2021.

Queer people in trades have very different experiences depending on whether they’re lesbian, bisexual or gay, or if they’re non-binary, a trans woman or a trans man. The former technically have had rights at work since the Ontario Human Rights Code changed to include rights for sexual orientation in 1986 due in part to grassroots and union activism, whereas the latter have less rights enshrined in law.

“There was a big push for getting women in the trades but [there] is definitely not that recognition or funding for queers to get into the trades,” says Castle. “There hasn’t been any specifically queer-oriented funding at all.”

Elyse, the carpenter and landscaper, says working for themselves is better because it allows them to escape “lots of different kinds of harassment from coworkers and bosses.”

ON THE JOB

The experiences of queer people in Toronto’s trades industry are not like those of other trades workers, according to sources we spoke to.

Very few queer tradespeople have a linear career path where they become interested in trades in high school, get into an apprenticeship, join a union and then work until they retire. Queer tradespeople also make less money in the trades. Partly in response to the severe discrimination queer tradespeople experience, they may go in and out of trades work, hold advanced degrees in unrelated subjects or take years off from working in trades.

Polly-Jean*, a trans woman who works mainly as a carpenter in film and television, says having an unorthodox career path is “certainly true” in her case.

“I’ve had a very unusual career trajectory. I’m more diversified than anyone I know across the subtrades,” she explains. “I have had other jobs, but I prefer to work in the industry — and I’ve also had so much trouble that I’ve tried to get out a number of times. I went back to school and got my teachers certification…because it's challenging to be all of yourself in these environments.

Similarly, Elyse the carpenter and landscaper got a degree earlier in life but works in residential renovations, specifically eco-friendly carpentry and permaculture landscaping. They are pursuing a Red Seal certification in carpentry, and often work for themselves with another carpenter to collect the hours they need for that certification.

Elyse says working for themselves is better because it allows them to escape “lots of different kinds of harassment from coworkers and bosses.” They add, “I often have to advocate for myself to be allowed to do certain types of work. For all these reasons, I eventually started my own business, so I can pick and choose more what I do and who I work with.”

The process of learning a trade is especially difficult for Elyse when they have to learn from people who don’t believe in their inherent capacity to do the work.

“I want to be a well-rounded carpenter, and be allowed to do heavier tasks. But it's like I do have to prove myself to do it. And then it's a lot of pressure cause if I fuck up anything, everyone is like, ‘I told you so!’ I'm less free to make mistakes when it comes to that stuff,” they explain. “I'm sure men make lots of mistakes during the learning process without the same kind of heckling. But then I also get heckling and creepy comments when I do a good job.”

Beyond comments, it's not unusual for workers to face forcible confinement, threats and physical assault in the workplace, especially those with multiple minority identities within an overwhelmingly cis straight male environment.

“Men think they need to prove their masculinity on the job site to each other. The easy targets become minorities, people of colour, women,” says Michelle Switzer, a trans woman construction worker and union advocate who says she’s faced physical threats on the job. “[They’re] talking about women, talking about sex, talking about how they are 100 per cent not gay.”

Construction sites are rough places, and the aggression can get physical, sometimes involving screaming, sabotage, theft of personal property, vandalism and more.

“I had one foreman that would keep giving me explicit instructions to do tasks in bad ways, and then ridicule me loudly to my coworkers…showing them what I had done,” says Lenny Olin, a queer and trans electrician who often wears nail polish and sports gay flags. “He would yell horrible humiliating things at me loudly, so everyone on that floor could hear. I tried to talk to someone above him in the company about it, but got no help there.”

“I had no choice but to quit. That's just one story, but I have countless others.”

Peter Arrow, 33, an electrician apprentice based in North York who identifies as a bisexual and Jewish cis man, attributes his safety on the job to being so big that no one can hurt him — or even want to threaten to hurt him.

“I am six-foot, two-and-a-half inches and 350 pounds — and that matters,” he says. “It matters more than I’d thought that it did.”

But Arrow adds that he has experienced discrimination against his religion.

“Like, using Jew as a verb — that’s not what I’m talking about; I’m talking about actual problems, like Nazi shit. And it's always the Jamaicans who stand up for me,” he says.

Working class environments in mining, manufacturing, and industrial or residential construction are complex. They’re spaces where ethnicity, gender and class intersect. In his 2000 ethnography of Toronto high schools, York University professor Daniel Yon traces unexpected alliances between working class students of different ethnicities and immigrants, some of whom have strong ties to the construction industry and impact the culture on worksites.

Construction jobs are rarely advertised on an open job market. Unions used to rely on their Hiring Hall lists, which is when unions source a large percentage of jobs from a list of out-of-work members; but these days, they’re relying more on “name-hiring,” which is when someone is hired by name, not by an application. That means it’s often about who you know in construction rather than how qualified or hard working you are. Non-union hiring is also usually done through personal networks.

Queers of all types, especially racialized queers, are often excluded from these networks. What’s more, they might be embedded in an ethnic network where it is better to remain closeted. Or, they might have a decent experience with a crew but are unlikely to find an equally welcoming environment elsewhere. This can all lead to people to stay in intolerable work environments for fear that things might be worse on another site, or that they might lose too much work. Many immigrants in trades are highly skilled, but may have limited English skills or accents that cause other workers to stigmatize them, leaving them especially dependent on ethnic networks with little access to a broader job network.

On worksites, there’s a significant division between the City of Toronto proper, and the suburbs and exurbs, according to Arrow. He and other sources we spoke to say that suburban and exurban workers, especially on bigger construction sites, tend to be whiter, more racist and more homophobic. Many Toronto construction sites are dominated by people from outside the city itself, which is especially a problem in racialized urban communities dealing with big infrastructure projects such as the Eglinton Crosstown LRT. Meanwhile, locals, especially Black workers, are locked out of these stable jobs, which are often only available through ethnic (largely European) and community networks they have little access to, Arrow adds.

The situation becomes even more complex for queer tradespeople who are closeted. Co-authored by Suzanne Mills, a 2022 study about closeted workers in the trades in Windsor and Sudbury, suggests that 63 per cent of LGBTQIA2S+ were not “out” to their employers or peers. Men who are queer, trans non-binary and other diverse genders are more likely to be closeted than women in trades.

In the LGBTQIA2S+ community at large, there can be stigma around being closeted. Some see it as a lack of pride, maturity or self-understanding. But in the trades specifically, being closeted or stealth is a decision that’s often made to avoid discrimination and to keep career opportunities, according to our sources. In fact, some queer tradespeople choose to be closeted or stealth at work, but be completely open about their sexuality or gender in their personal lives. In Mills’ study, 63.6 per cent of queer workers in trades and related industries surveyed were only closeted at work.

“There are a lot of reasons that people — mostly men — choose to be closeted, or choose to lie or not share details about their sexualities and genders. One is not wanting to face direct discrimination, and wanting to fit in with the others,” Olin, the electrician, explains.

“But another somewhat more complicated thing is just that there are many men who have sex with men that consider themselves straight or perhaps just don't use labels like gay/straight/bi, etc. Similarly for gender. There are a lot of people living gender non-conforming lives that don't have or use language around trans identities.”

To survive on job sites, electrician apprentice Peter Arrow is highly attuned to social dynamics at work.

Survival Strategies

Many queer tradespeople we spoke to told us they avoid working as unionized workers on large construction sites where they are more vulnerable.

Particularly for those who feel unable to pass as cis or straight, work small-scale and informal jobs to help them avoid the discrimination inherent in large worksites; this gives them more control over their job environments. But working small-scale can lead to intense loneliness and isolation since there are seldom more than three people on site, and it’s possible to not speak to another person all day. These factors can contribute to mental health challenges, and also present a barrier to getting certifications like a Red Seal, or gaining access to more restricted trades.

In construction, when you finish a job, you move to a new site. That means crews are constantly changing. To survive, Arrow is highly attuned to social dynamics at work.

“Every time I come on a new site, I look for the person who is going to be the biggest problem, and the biggest ally and who has the most social capital,” he explains. “I am constantly playing a social chess game to protect my safety. Also, because not being out is exhausting, so my goal is to be out as quickly and safely as possible. It usually takes about a month [for me to come out].”

Whereas for Elyse, the carpenter and landscaper, they find it’s best for their mental health to just focus on work and avoid colleagues. “Noise-cancelling Bluetooth headphones are the best life hack. I can now literally tune out people I don't wanna hear and it really helps with the anxiety,” they say.

One of the reasons why Elyse got into trades was to escape the constant pressure in university-track career to present a certain way — a pressure they say doesn’t exist in construction.

“It's quiet a lot of the time. You don't always have to be in a good mood. You get exercise and satisfaction from your work. It's super rare to be a woman-looking person in the world who doesn't always have to smile and be pleasant,” they explain. “I can put on my headphones and be grumpy and do demolition when I'm in a bad mood, and no one calls me a crazy bitch. They are just like, ‘Wow, cool! You did that fast.’ It's very therapeutic.”

While physical health disparities are less likely between straight and gay tradesmen, the latter are three times more likely to report poorer mental health than their counterparts, according to the SRDC report.

What’s more, the report adds that “sexual minority groups” have significantly lower median annual incomes than heterosexual men ($77,500) and heterosexual women ($65,680), with queer men experiencing wider income gaps ($58,420), followed by queer women ($56,990). Queer women, who account for a fraction of workers, make the lowest income in the industry, face career sabotage for being out, and experience the worst physical and mental health outcomes. At 16 per cent, they are twice as likely to report poorer physical and mental health than their heterosexual counterparts.

Still, even with these income disparities, trades jobs can be good jobs for queer people who face discrimination in all fields, according to Olin.

“These years, I love queering up a job site. I'm in a union and I know that I will be able to get another job if I face too [many] discriminatory or hostile attitudes,” Olin says. “I am extremely glad I went into trades. If someone wants a good paying job with all the perks, I definitely urge them to consider construction.”

Lenny Olin, an electrician, recently co-created a new cross-trade organizing and social space called Hi-Viz, which welcomes union, non-union and informal workers.

QUEER TRADES HISTORY

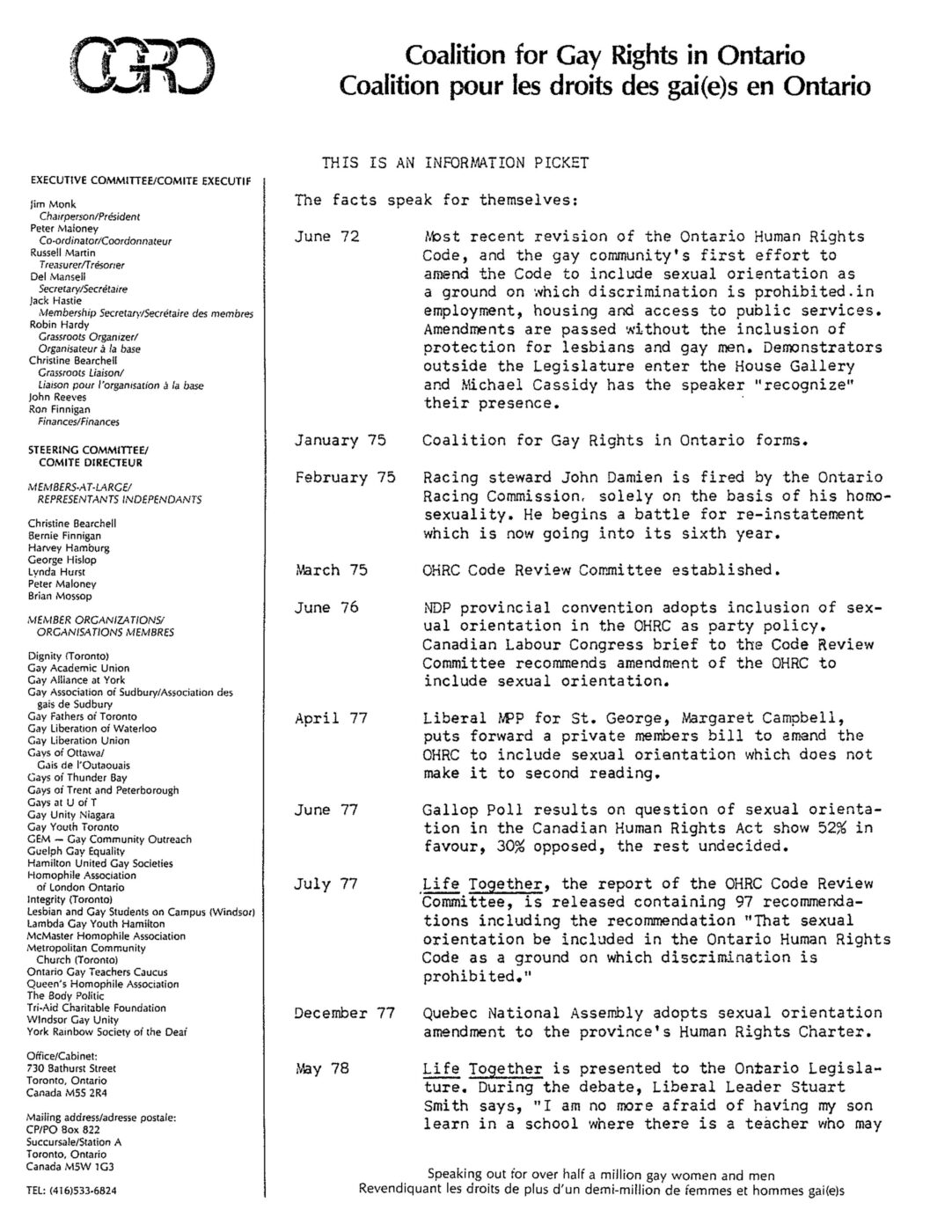

Despite recommendations by the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) in 1977, Queen’s Park would renege on amending the Human Rights Code to include “sexual orientation” until 1986.

It would take another 14 years for the policy framework for these protections to be written in 2000. Eventually, in 2012, gender identity and expression were also enshrined.

Ninety-seven recommendations to amend the code were presented and debated in Ontario in 1978. Two years later, in 1980, the then-ruling Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario planned to adopt all of them in then-labour minister and MPP Robert Elgie’s Bill 209 — except the inclusion of “sexual orientation.”

“All three parties in the legislature are running scared from gay rights because they anticipate a spring election,” the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Ontario (CLGRO) said in a protest ticket from 1981, now stored in the Toronto LGBTQ2+ Arquives.

“It is time we made the lofty claims of the code’s preamble a reality, and not just rhetoric,” the lobby group said, when it was originally the Coalition for Gay Rights in Ontario (CGRO).

Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Ontario (CLGRO) protest ticket from 1981, now stored in the ArQuives, one of the largest independent LGBTQIA2S+ archives in the world and the only archive in Canada with a mandate to collect at a national level.

Typewritten letters between the CGRO and MPPs during the 31st Parliamentary session, also stored at the Arquives, reveal a political climate in Ontario that was hostile to gay men and other sexual minorities between the 1960s and 1980s; this eventually boiled over, resulting in the infamous bath house raids by Toronto Police in February 1981.

While pro-LGBTQIA2S+ activists called out the Ontario PC Party for strong-arming gay rights out of its legislation to amend the code, they criticized the Ontario Liberal Party and Ontario New Democratic Party for reneging on their support.

Letters from Elgie and Liberal MPP Bernard Newman, who tabled similar legislation in the same session, revealed broad support for the omission of gay rights. “As all sides of the legislature are divided on this issue, I would prefer that the physically handicapped first be accommodated,” Newman wrote.

NDP MPP Michael Cassidy was a promising supporter of equal rights for gay, lesbian, and bisexual men and women since his election in 1971. At the opening of his first session, he requested that the attendance of gay rights activists, who had entered the public gallery, be written into record. Cassidy wrote several letters during his tenure in support of including sexual orientation in the amendments to the code. But by the end December 1980, he said this in an interview with the Toronto Sun about the ongoing debate: “A gay rights amendment ‘is not a priority at this time.’”

“When they aren’t busy killing us, society sure makes it damned difficult to live,” CGRO’s then-secretary treasurer Harold Desmarais said in an address to the Toronto Metro Labour Council (now Toronto & York Region Labour Council) in April 1980.

“Labour has always been in the forefront of minority struggles,” Desmarais added in the same address to electricians, steel workers, plumbers and automotive workers from across Toronto. “The entire union movement is built on two very basic tenets: One, every person has a right to dignity and equal treatment and two, every person has a right to a job.”

One of the first labour unions to adopt a resolution on sexual orientation sprang from an industrial centre of Ontario’s mining and automotive industries. In October 1976, the Windsor and District Labour Council adopted a resolution to protect queer workers, adding “sexual orientation” to its discrimination provisions.

The Ontario New Democrats adopted this mission to encode gay rights to its official party policy at its provincial convention that same year. And soon, the Ontario Federation of Labour (OFL) followed suit

In 1979, the Oshawa Labour Council submitted the only resolution on sexual orientation to the OFL’s annual convention agenda. The following resolution, No. 73, was adopted by the provincial union on Nov. 29, 1979: “Gay and lesbian workers are subjected to various kinds of discrimination and harassment with respect to jobs, accommodations and other human activities. Therefore be it resolved that the Ontario Federation of Labour urge the Ontario Government to broaden the Human Rights Code to eliminate this discrimination.”

Dot S. (pictured right with her wife on the left) was possibly the first electrician to openly transition to female in Toronto at a time when there were very few women electricians in Ontario.

FIRST ON THE FRONTLINES

Dot S. was a trans woman trades worker during this time.

I spoke to Dot and her wife at their home in a city in Durham Region. Dot, who grew up in Scarborough, always knew she was a woman. She was trans but closeted at work for decades throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s, and finally transitioned at work in the mid-90s. Dot was possibly the first electrician to openly transition to female in Toronto at a time when there were very few women electricians in Ontario. She had a full career, raised a family with her wife and is now retired.

But Dot doesn't want any accolades, and says joining IBEW Local 353 and becoming a Red Seal electrician as a man was “cheating” during a time when it was very difficult for women to break into the industry, so she doesn’t want any laurels. Although Dot had success in the trades, she struggled with dysphoria, and describes being closeted as “horrible.” That’s why Dot took the first opportunity to transition at work, though she struggles to name exactly when this happened as it was a gradual process that finished in the mid-90s.

Construction sites are physically dangerous for anyone, but for queer tradespeople, workplace accidents are perceived through the lens of someone’s sexual orientation or gender. This was especially the case in the 20th century when workplace safety was taken less seriously. Dot’s work in traffic controls and lights was dangerous due to the electrical danger, working at high heights in bucket trucks and lifts, as well as beside busy roads. In the mid-2000s, Dot had two co-workers who died doing traffic electrical on the road while working in a lift when it was hit by a bus — an incident that she says affected her deeply.

Dot herself got an electric shock in a bucket truck, and the strength of the shock caused muscle contractions where she couldn’t let go (known as being “held up”). Eventually, a team of high-voltage electricians nearby tried to help Dot, but EMS couldn't figure out how to rescue her from the bucket at the height she was working. She was eventually transported to the hospital, where she received medical treatment, but this was stressful because it exposed her gender identity during a time when she was closeted. Here’s how Dot describes what happened:

Dot came out shortly afterwards, and faced serious issues throughout her career. She says constant dead-naming and verbal discrimination didn’t bother her as much as finding “packages” in her truck that contained human feces, or when other service trucks played the song “Man, I feel like a woman” on repeat wherever she came around.

Although she was also a skilled industrial electrician and foreman, Dot focused on working in traffic lights and controls, which was work that could be done by herself. Dot struggled with intense loneliness at work and on her commute, she often called her wife on the phone to deal with the isolation of being alone on the road all the time. After hours, Dot was busy both with her family life, as well as with extensive organizing among women in trades and broader trans advocacy, retiring recently after a distinguished career as an electrician and advocate. Today, Dot and her wife spend a lot of time with their grandchildren, and she continues to be deeply engaged in advocacy work.

Jonas Spring is president of Landscape Ontario's Toronto chapter.

BUILDING CHANGE NOW

Today, while there are seeds of growth, organizing for LGBTQIA2S+ people in trades has yet to develop roots.

The lack of institutional organizing goes hand in hand with the lack of data; it’s a chicken and egg problem with minimal data to demonstrate systemic problems, so there’s no funding for organizations to demand that data be collected. Other equity-seeking groups like women, and to a lesser extent racialized people, have provincial or federally funded equity programs. For example, there have been programs that provide cash bonuses for hiring women. Mentorship, pre-apprenticeship programs and tool familiarization programs are also funded for several underrepresented groups, including women, racialized youth and Indigenous people.

Although many women in trades initiatives are technically trans inclusive, Castle, the owner of Three Dollar Bill, says it feels limiting.

“Ultimately would you want to be lumped into that? I came into my dignity actively being a trans person,” they explain. “If you put yourself in the category of women in the trades, that clumps you into this idea, and the government and funding reinforcing the same binary.”

It’s the same situation with advocacy groups and NGOs. The Toronto Community Benefits Network (TCBN) does lobbying at several levels of government to try to ensure that marginalized people get jobs on projects in their own communities. Like many advocacy groups, TCBN tries to include LGBTQIA2S+ people in its mandate, but it's not the network’s primary focus. There are advocacy groups dedicated to marginalized youth, such as Hammer Heads, and those serving women such as Sisters in the Trades and OBCTradeswomen. But historically, there’ve been no equivalent groups dedicated to LGBTQIA2S+ in construction trades, though a new group for trans and gender non-confirming tradespeople in the film industry recently emerged in 2021.

Polly-Jean, the carpenter who mostly does film and television work, is the lead organizer of the newly created Alliance of Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Tradespeople (ATGT). She says there hasn’t been much advocacy in the trades for trans and gender non-conforming people until recently.

“I think there was nothing. I was looking, and I was looking for international organizations also within my union and within other unions for anything like this — and there but wasn’t,” she explains. “There were some underground things starting around the same time; just a few isolated pockets.”

Recently, there've been new developments in organizing within existing trade unions and community groups, both grassroots and union sponsored. The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) launched a pride committee, and started participating in Pride Toronto in 2022. Simultaneously and separately that same year, Carpenters Local 27 also started marching in the Pride parade; this was the first year that construction trades unions had participated in Pride, and both groups have continued to march in the parade since then.

(We sent questions to local unions and colleges to learn about the experiences of LGBTQIA2S+ trades workers experience at work and school, including their inclusion, funding opportunities and documented harrassment. Read their responses here.)

What’s more, some queer tradespeople including Olin, the electrician, recently co-created a new cross-trade organizing and social space called Hi-Viz, which welcomes union, non-union and informal workers. Attendees meet once a month in various locations across Toronto, including Three Dollar Bill and Glad Day Bookshop in Church-Wellesley. There’s hope that activism may emerge from the networks built, and an understanding that it’s also beneficial to gather with people who relate to your struggles.

“Personally, I just want to help connect queer and trans people that work in construction trades. I always need more of such connections and talking to others; it seems like that is true for many others, as well,” Olin says. “It can be really isolating spending day after day in these extremely heteronormative and often very discriminatory and hostile work environments.”

“I am extremely excited to see what may come from all of these new connections.”

Here's your chance to support the only independent, hyperlocal news outlet dedicated to serving gen Zs, millennials and other underserved communities in Toronto. Donate now to support The Green Line.

PART 3

BLUEPRINTS FOR CHANGE: DRAG SHOW and COMMUNITY GATHERING FOR LGBTQIA2S+ IN TRADES

A drag performance, panel discussion and social hosted by The Green Line and supported by Hi-Viz.

About the Event

It's time to look at one of our city’s biggest problems — construction — through a new lens. Supported by Hi-Viz, The Green Line is hosting a panel discussion and social focused on the experiences of Toronto’s LGBTQIA2S+ tradespeople. Attendees will have the chance to listen to the experiences of queer folks who navigate professional careers in construction and other trades, then gather in small groups to generate community-led solutions. Our ticketed event has limited capacity, so please RSVP before spots fill up.

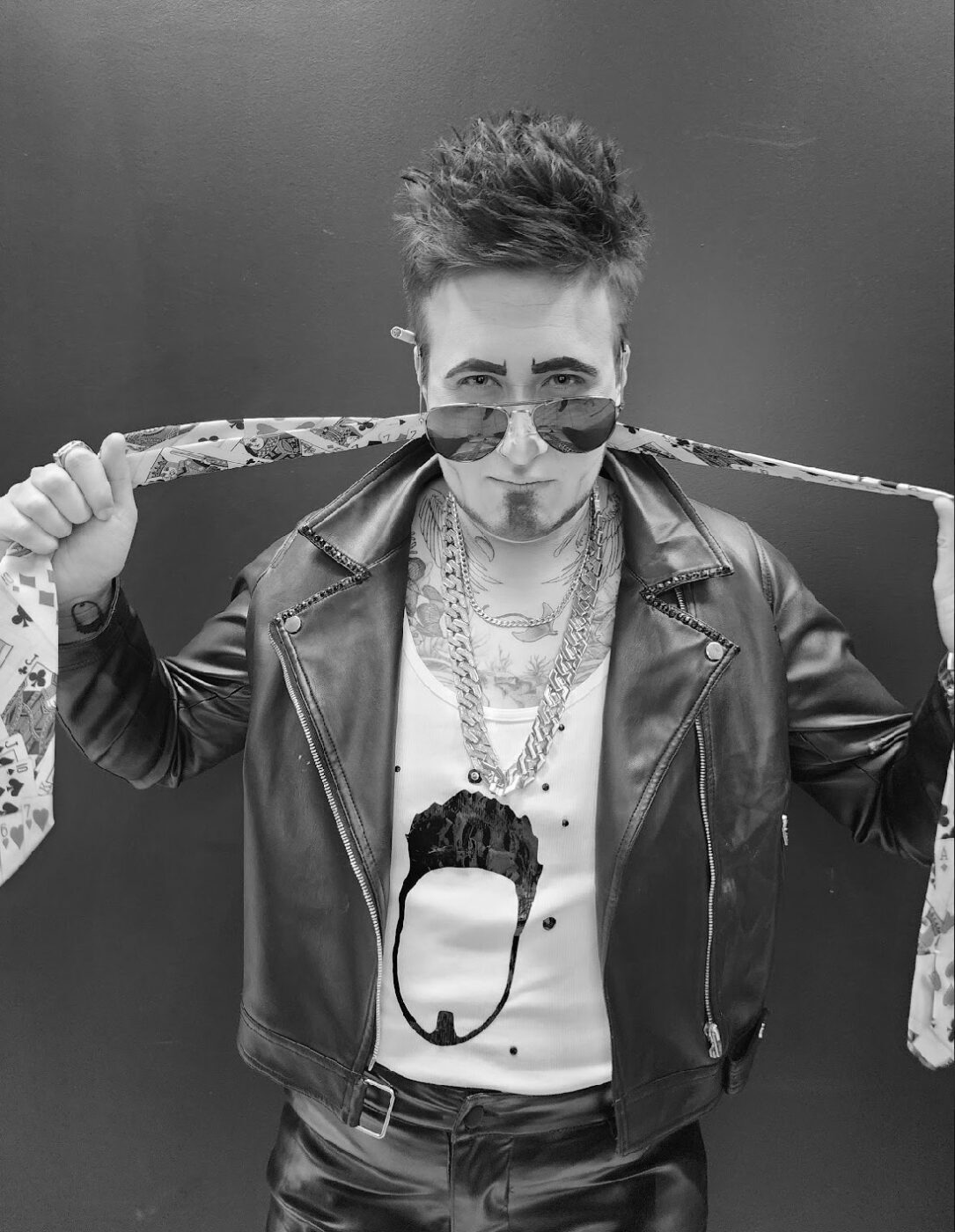

On the same evening, we're also super excited to host a construction-themed drag show by Justin Cider! Did this Drag King just step off of GQ Magazine? This king, who's a proud member of the Haus of Devereaux, exudes a confident swagger and magnetic charm that turns heads everywhere he goes. Justin has won titles such as Mr. Port Hope, and continues to make his mark in the drag scene and pageantry! Don’t miss this incredible entertainer. Buy your ticket now for our in-person event. If ticket cost is a barrier, please email us at hello@thegreenline.to.

Events are an essential part of our Action Journey. We want to empower Torontonians to take action on the issues they learn about in The Green Line — so what better way to do that than by bringing people together? From community members to industry leaders, anyone in Toronto who’s invested in discussing and solving the problems explored in our features is invited to attend. All ages are welcome unless otherwise indicated. Our only guidelines? Be present. Listen. Be kind and courteous. Respect everyone’s privacy. Hate speech and bullying are absolutely not tolerated. At the end of the day, if you had fun and feel inspired after our events, then The Green Line team will have accomplished what we set out to do. Any questions? Contact Us.

ELYSE

LUE-MAYO

Elyse Lue-Mayo is a third-year apprentice in general carpentry. They started their own business in 2023 as a general contractor specializing in eco-friendly construction, renovations, and landscaping and hardscaping. Elyse was also a permaculture landscaper and gardener for many years launching their business. Elyse identifies as genderqueer/queer, mixed-race (Trinidadian-Chinese and Irish), autistic and ADHD. Their goal is to get their Red Seal in carpentry so they can apprentice other people and make the trades more accessible to those who are marginalized in the industry. Elyse is also interested in how to facilitate building and gardening projects for low-income communities.

MICHAEL

BRAITHWAITE

A tireless advocate for people experiencing homelessness, Michael has over 30 years of experience creating innovative solutions to better support vulnerable people. Michael is CEO of Blue Door, secretary on the Canadian Housing and Renewal Association’s Board, and on the Board of the youth homelessness-focused organization A Way Home Canada. At Blue Door, Michael helped launch Blue Door’s first employment social enterprise called Construct, three supportive housing programs including the first safe space for LGBTQIA2S+ youth in York Region, the national housing and homelessness podcast On The Way Home, and is leading the creation of the first affordable housing land trust in York Region, Housing For All Land Trust.

KAITLYN

SMITH

Kaitlyn Smith is an immigration reporter and freelance data journalist. They report breaking news, analyze new survey data and research, and scour archives for long-form articles. Smith also leads workshops about trauma informed reporting on LGBTQIA2S+ and BIPOC communities. Both their investigative data analysis and breaking news about international student tuition fees and accessibility to citizenship in Canada earned nominations in 2023. Smith is a University of Toronto Scarborough journalism program alum, live storytelling enthusiast and skills picker-upper.

LENNY

OLIN

Lenny Olin is an artist, electrician and community organizer. In 2023, Lenny was part of establishing Hi-Viz, a monthly social for 2SLGBTQ trades workers to gather for networking, project development and mutual support. Lenny has been doing community-based organizing since 1988 with focuses on anti-poverty and low-income housing, disability justice, migrant rights and Indigenous sovereignty. Lenny received a BFA from Emily Carr University in 1997 and has been a Red Seal-licensed electrician since 2020. When not on a construction site or at the union hall, Lenny can often be found on dance floors or making ornate cakes.

PART 4

BUILDING BRIDGES AND CRAFTING FUTURES

Event Overview

See what you missed

from our latest event.

Our community members brainstormed solutions to combat industry barriers to queer tradespeople in Toronto.

Compiled by Adele Lukusa.

Panellists Michael Braithwaite (far left), Lenny Olin (centre left), Kaitlyn Smith (centre right) and Elyse Lue-Mayo (far right) speaking at our July Action Journey event, Blueprints for Change: Drag Show and Community Gathering for LGBTQIA2S+ in Trades, held in Three Dollar Bill in Parkdale on Thursday, July 25, 2024.

📸: ANTHONY LIPPA-HARDY/THE GREEN LINE.

Drag king Justin Cider performing at our July Action Journey event, Blueprints for Change: Drag Show and Community Gathering for LGBTQIA2S+ in Trades, held in Three Dollar Bill in Parkdale on Thursday, July 25, 2024.

📸: ANTHONY LIPPA-HARDY/THE GREEN LINE.

Signage outside of Three Dollar Bill in Parkdale, promoting our July Action Journey event, Blueprints for Change: Drag Show and Community Gathering for LGBTQIA2S+, on Thursday, July 25, 2024.

📸: ANTHONY LIPPA-HARDY/THE GREEN LINE.

Attendees discussing barriers and solutions to queer tradespeople in Toronto during a Story Circle at our July Action Journey event, Blueprints for Change: Drag Show and Community Gathering for LGBTQIA2S+ in Trades, held in Three Dollar Bill in Parkdale on Thursday, July 25, 2024.

📸: ANTHONY LIPPA-HARDY/THE GREEN LINE.

SOLUTIONS

ACTIONS

Do something about the problems that

impact you and your communities.

Get

Certified

For tradespeople looking to upgrade their skills, this program offers them credibility and accreditation in their field of work.

Learn

the Ropes

Brought to you by Youth Employment Services (YES), Yes2Trades offers those in the GTA between 16 and 29 years old a 20-week head start into the trades.

Be

Social

Join this cross-trade organizing and social space that connects queer tradespeople.

Join Our

Community

Continue the conversation with other Green Line community members.

Attendees at our July Action Journey event, Blueprints for Change: Drag Show and Community Gathering for LGBTQIA2S+ in Trades, held in Three Dollar Bill in Parkdale on Thursday, July 25, 2024.

📸: ANTHONY LIPPA-HARDY/THE GREEN LINE.

Supporting The Green Line means supporting Toronto. Join our membership program today, so you can redefine our city as you see it.