PART 1

TORONTO IN TWO PANDEMICS

A person walks along Richmond Street East in downtown Toronto next to a sign that says, "We are all in this together."

KAYLA ZHU

Vancouver native, Ryerson (X) University journalism graduate and long-time K-pop fan. Enjoys climbing mountains, learning about data visualization and throwing frisbees.

April 1, 2022

Two years of COVID-19 have pulled back the curtain on the city's worsening inequality and polarizing individualism.

A focus on individuals over the collective good has only become more pronounced during the pandemic.

"We are all in this together" has become the choice slogan for governments and corporations to express solidarity during these challenging times. But are we really "in this together"?

A person wearing a mask rides a TTC streetcar at night.

Toronto reported its first "presumptive" case of COVID-19 on Jan. 25, 2020. The Ontario government closed all non-essential businesses across the province — the city's first lockdown — on March 23, 2020.

For many, the first wave in spring 2020 was met with financial uncertainty. The second wave in fall 2020 was a hard pill to swallow after a short-lived reopening in the summer. The third wave in spring 2021 came amid Toronto's confusing vaccine rollout. The fourth wave, in September 2021, was met with cautious optimism due to high vaccination rates. The fifth wave, in December 2021, saw the Omicron variant infecting thousands of Torontonians a day.

As of March 15, 2022, in Toronto, there has been:

- Five waves of COVID-19

- 282,217 confirmed cases of COVID-19

- 4,109 deaths due to COVID-19

- Over 270 days of lockdown for indoor dining between 2020 and 2021 — the longest in North America.

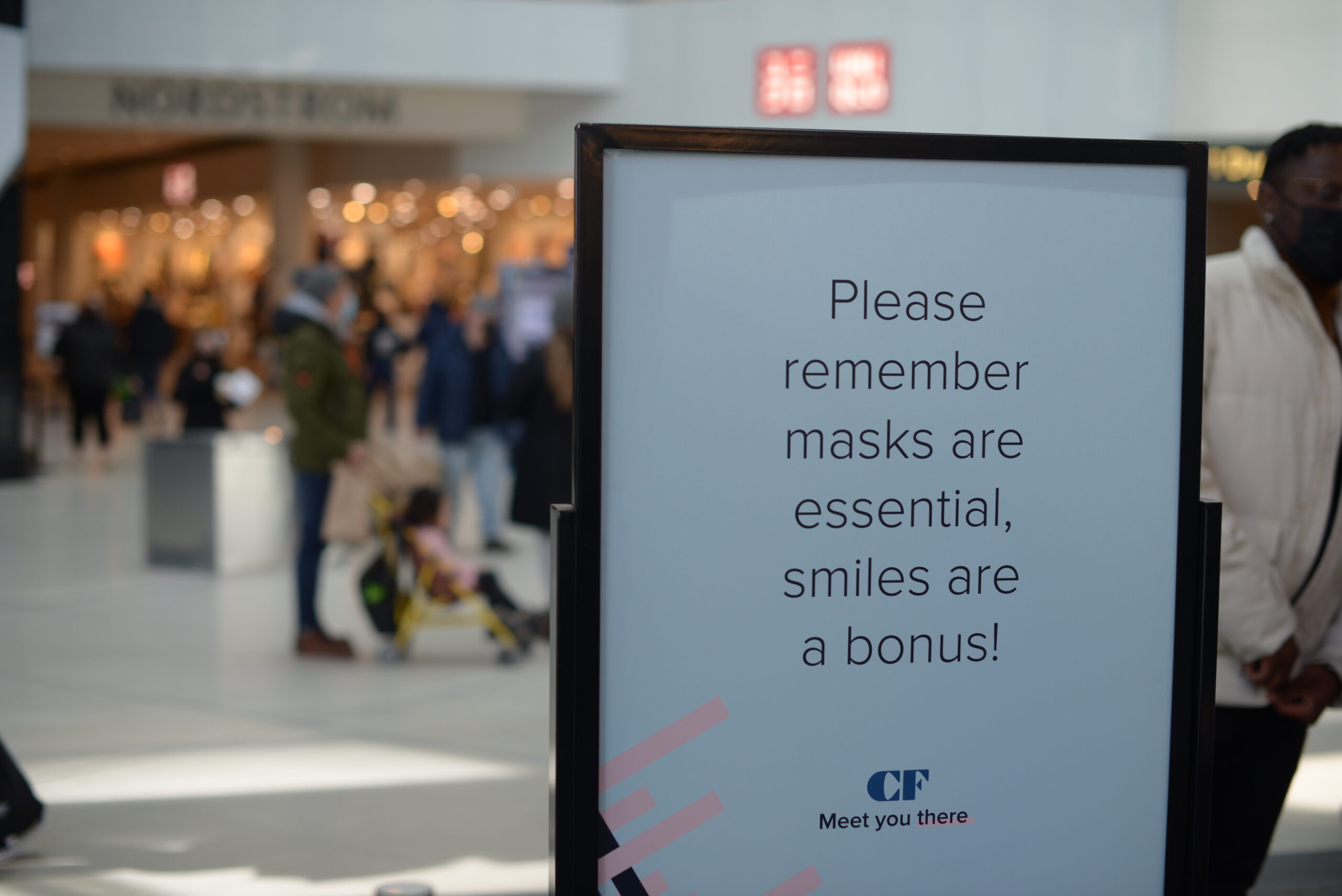

A sign in the Eaton Centre in downtown Toronto reads, "PLEASE REMEMBER MASKS ARE ESSENTIAL, SMILES ARE A BONUS!"

Scenes of polarizing individualism have stood out over the course of the pandemic.

The early months of COVID-19 had Torontonians cleaning out toilet paper and other essential items from grocery store shelves.

Later on, anti-vaccine and anti-vaccine mandate protesters blocked access to hospitals and other essential services in the name of individual freedom.

Getting tested also became a free-for-all, with Torontonians bouncing between government testing sites and private companies to get their hands on COVID-19 test kits.

A taped-up hoop at an outdoor basketball court in Toronto.

Public health measures have largely emphasized personal choice and responsibility, such as staying at home if you feel sick and self-isolating if you show symptoms.

By March 21 of this year, Ontario lifted all mandates for most indoor settings, including those for vaccines and masks.

"If you want to keep your mask on, keep it on. If you want to take it off, take it off," Ontario Premier Doug Ford said during the March 9 announcement at a press conference.

Some Torontonians have said they feel as if they've had to figure out how to get through the pandemic on their own, from assessing the risks of going out and socializing to accessing testing and vaccines.

Immunocompromised people, parents of young but not yet vaccinated children and other vulnerable populations have expressed feeing left behind by the city's pandemic response.

"IF YOU WANT TO KEEP YOUR MASK ON, KEEP IT ON. IF YOU WANT TO TAKE IT OFF, TAKE IT OFF."

ONTARIO PREMIER DOUG FORD

COVID-19 isn't Toronto's first pandemic.

The 1918 influenza pandemic — commonly known as the "Spanish Flu" — ravaged our city after soldiers returned home from World War I. But Toronto responded differently back then.

A sense of collective duty and civic engagement born out of Toronto's wartime efforts shaped the city's response to the Spanish Flu.

Sophisticated, grassroots volunteer networks worked in tandem with government agencies to support Torontonians during the pandemic. Volunteer groups supported relief efforts by cooking meals in public kitchens for families in need and responding to families' requests for help on card surveys that were distributed across the city by postal workers.

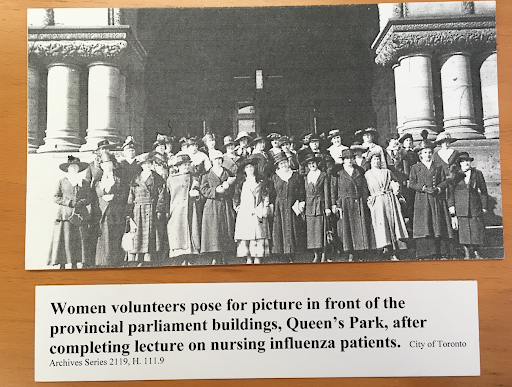

Women volunteers pose for a photo in front of Queen's Park after completing a lecture on nursing influenza patients during the Spanish Flu.

Two pandemics, two eras.

After reading this explainer head over to Part 2 to check out our interactive, solutions-focused feature that compares the two pandemics in Toronto. Then register for our community event in Part 3!

Tell us: What insights from the past can help us navigate the present?

Today’s stories lead to tomorrow’s solutions, so sign up for our newsletter to take action on the issues you learn about in The Green Line.

PART 2

LIVING WITH COVID IN TORONTO:

WHEN YOU FEEL ALONE EVEN THOUGH 'WE'RE ALL IN THIS TOGETHER'

STEVEN ZHOU

An investigative journalist, producer and editor based in City Place focusing on extremism, politics and Islamophobia.

April 11, 2022

Torontonians sit in a TTC subway car.

Not long after the first coronavirus case was confirmed in Toronto on Jan. 25, 2020, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau appeared in a string of daily morning press briefings where he repeated some form of the phrase, “We are all in this together.”

On March 18, Trudeau declared, “We are all in this together, and we are there for you.” Earlier in the week on March 16, Ontario Premier Doug Ford announced, “Your government has your back.” And later that same day, Toronto Mayor John Tory said, “We must take unprecedented action to help our residents.”

Soon, the words “We are all in this together” popped up across our city, printed on T-shirts and scrawled on posters taped to shuttered shops — likely someone’s attempt to lift the spirits of their fellow Torontonians. But the phrase eventually congealed into cliché. People wanted to feel a sense of civic connection amidst a global health crisis, but a more complicated reality has emerged over the past two years.

Although the sentimental, throwaway slogans fit for Hallmark cards are easiest to foreground, COVID-19 threw decades of systemic inequity into sharp relief. Signs of deepening inequality and polarizing individualism were present in Toronto long before the pandemic’s arrival.

In June 2020, Statistics Canada asked Canadians to rate their overall life satisfaction on a scale from one to 10, with 10 being the most satisfied. The results? Canadians reported the lowest level of satisfaction since 2003, at 6.7. The average number in 2018 was 8.1.

COVID-19 has clearly taken a toll on us, but assessing the pandemic’s exact impact remains tricky. Statcan’s coronavirus reports consider “social contacts” — a tough thing to quantify and measure — as a pillar of life satisfaction. It’s easier to count sick people and lost jobs. Yet the quality of our relationships is something we all feel in our bones. Lockdowns, quarantines and social distancing have, by all indicators, eaten away at the frequency of human interactions, which when added up, amount to what we loosely call “community.”

According to Google Trends, searches for the term “community” peaked the highest in years right around Toronto’s first lockdown in late March 2020, then surged even higher the following spring 2021.

But not everyone recalls this intimate, neighbourly pre-COVID society we were all apparently enjoying.

In 2019, an Angus Reid-Cardus study reported that a third of Canadians “could not definitively say they have friends or family members they could count on to provide financial assistance in an emergency.” Nearly a fifth said they “aren’t certain they’d have someone they could count on for emotional support during times of personal crisis.” Only about 14 per cent characterized their social lives as “very good.”

In other words, loneliness and fraying social relations were becoming bad enough to impact Canada’s public health.

“We are so sad because we have been told and sold that being independent is the best,” Yvonne Su, a York University equity studies professor specializing in migration and post-disaster recovery, told The Green Line. “So we are becoming increasingly isolated alone since community isn’t good for capitalism. Community means shared resources and less money spent.”

Su added that those exhausted by the pandemic are too drained to think about bringing people together for social change. “We see the stark inequality [in] our current political, cultural and social climate in Toronto, Ontario — even Canada — and it allows us to say, ‘We need to look out for our own family right now. We can’t help others,’” she explained.

Headshot of York University equity studies professor Yvonne Su.

We often hear that solutions to our problems await us in the future in the form of emerging technologies or new models. We’re never really told to look back. Yet 2020 isn’t the first or only time that the world — or Toronto for that matter — was plunged into a global pandemic. The city had to respond to a mass crisis over a century ago when another deadly disease overtook the world. There was no social media to help organize neighbourhood responses, yet people still did.

Combing through these past solutions reveal more than a few useful approaches for how we can band together against a pandemic. What emerges is a Toronto that more ably mobilized its residents to work through collective challenges together, from war to disease. In order to examine what our somewhat forgotten past has to teach us, we first have to travel back in time.

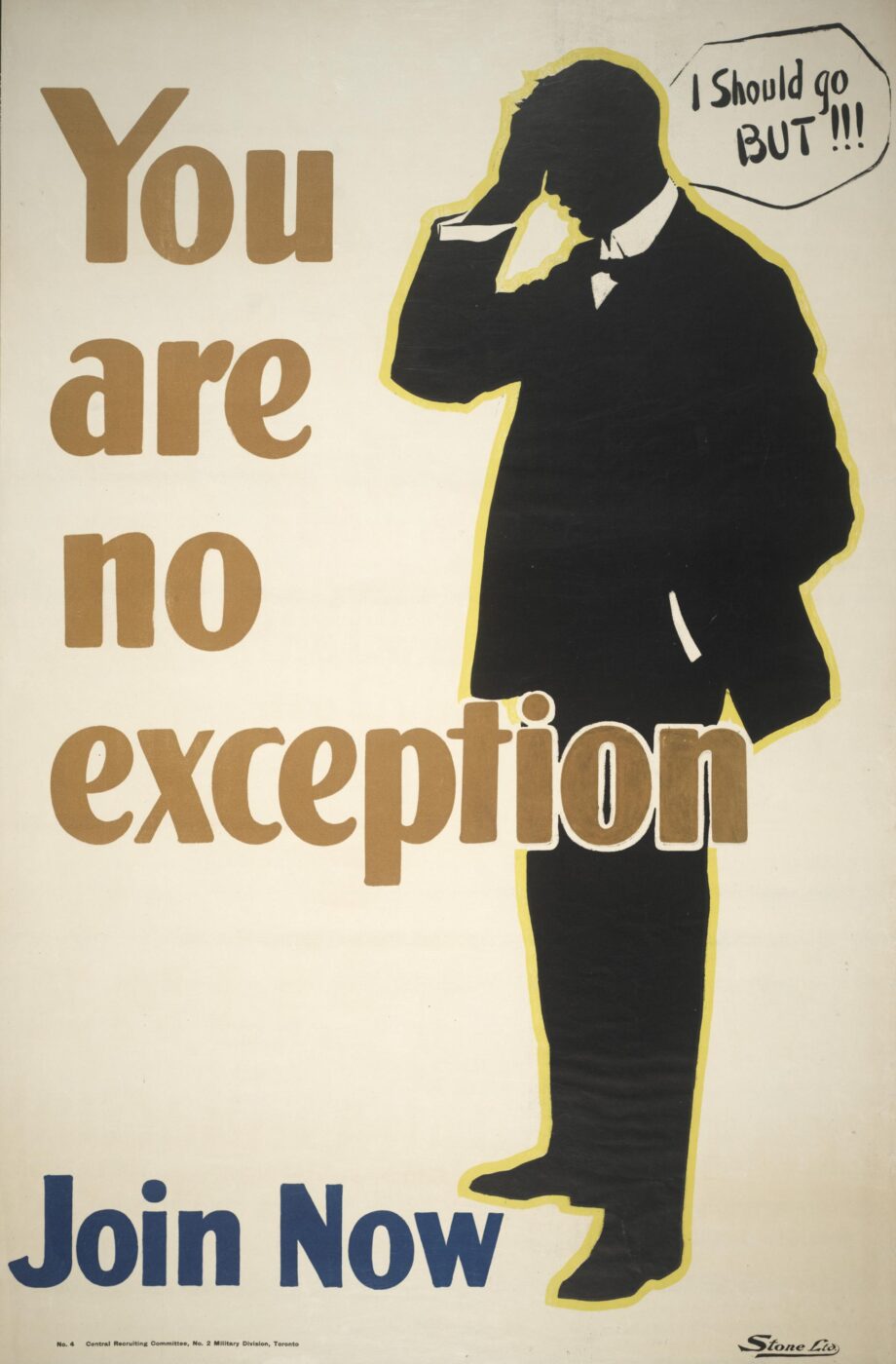

World War I recruitment poster.

World War I catalog.

World War I recruitment poster.

Toronto 1918: War

Just over 100 years ago, Toronto was trying to survive yet another, even deadlier, global pandemic.

The Spanish Flu swept across the world thanks in part to soldiers travelling from one country to another during and after World War I (1914-18). Toronto, just growing out of its previous life as a modest colonial capital, was thrown from the war effort into a different kind of war.

The pandemic was devastating but, along with WWI, it induced social changes that sharply contrast with today’s socially divided lifestyles. A draft meant many Canadians were personally invested in the war. Many women weren’t happy to simply stay home while their husbands were sent to the trenches. A sense of collective duty took shape, thanks to that most unifying of forces: a common enemy.

The result was an impressive volunteer culture that popped up across Canada, including in Toronto. As WWI wound down, the civic and volunteer machinery already in place — thanks to one of history’s most violent events — kicked into high gear in the fall of 1918. It helped Toronto withstand perhaps the deadliest virus ever.

This broad civil society effort contrasts sharply with today’s more freelance networks of scattered mutual aid, which try their best to look out for those left behind. But a lot has changed in 104 years. There’s no official volunteer structure in place made up of fleets of nursing aides or centrally organized food delivery.

Two eras, two different sets of responses. Although altruism is the throughline, the divergent ways it took shape reflect broader social changes over the course of a century.

Back in 1918, Toronto was just starting to come into its own when Canada threw its weight behind Britain and the Allied powers. Four anxious years later, most of the city wasn’t expecting a showdown with a deadly virus. An ocean away from the main theatres of fighting and disease, Canada seemed like a safe outpost.

That all changed with the death of a little girl.

Medical personnel battling the Spanish Flu in Toronto.

TORONTO 1918: PANDEMIC

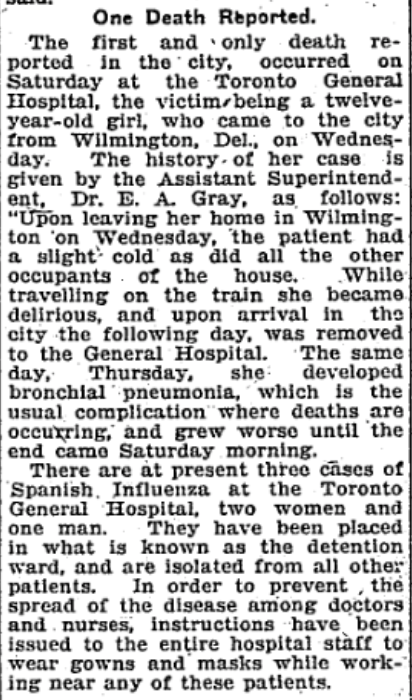

In retrospect, more people should’ve panicked over the death of Vera Isabel Robertson, and not just because of her age.

The little girl from Delaware was only 12 years old when she died in Toronto General Hospital on Sept. 29, 1918.

In Toronto for just a few days, her death was recorded in The Toronto Daily Star (later The Toronto Star). The small obituary now looks gloomy and foreboding in light of what was to come. One word included in her cause of death said it all: influenza.

Anonymous report of Robertson’s death in The Toronto Daily Star’s Sept. 30, 1918 edition.

Already prevalent in a world ravaged by unprecedented global warfare, this particular strain of influenza — later named H1N1 influenza A — grew in 1918 into a pandemic that infected hundreds of millions of people and took up to 50 million lives. And because Spain, a neutral country in World War I, was the only nation that reported extensively on the disease’s effects as the war wound down, the pandemic gained a rather xenophobic misnomer: “The Spanish Flu.”

By September 1918, it was clear that the flu had walked right into the heart of Toronto, as patients with influenza symptoms filled up hospitals. Yet Vera’s case, along with a dozen more infections, didn’t fluster Canadian health authorities who couldn’t predict how bad things would get.

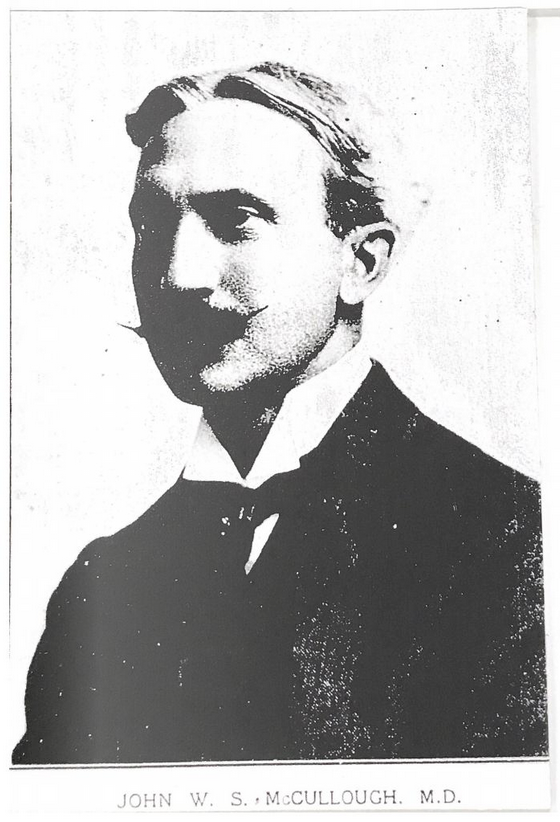

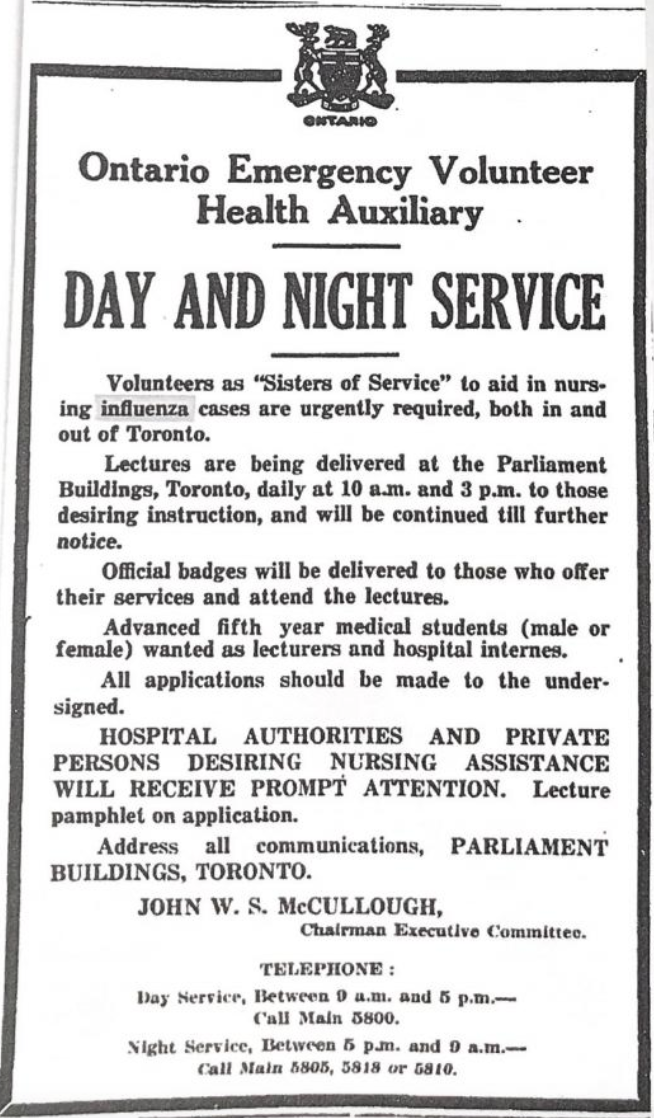

“My own opinion is that anything further that might be said would not be in the public interest,” said Dr. J.W.S. McCullough, Ontario’s provincial medical health officer, when asked about what should be done next. “I also think the public has been unduly alarmed already.”

Dr. J.W.S. McCullough, Ontario’s provincial medical health officer, in 1918.

Dr. Charles Hastings, Toronto’s medical officer of health who overlooked the city’s public health system, likened the new virus to the annual flu or “grippe.”

“There is no necessity for hysterics on the part of the public,” Hastings told The Star. “It is that which helps to sap their vitality and exposes them to such epidemics. It is just ordinary grippe, and no worse than we have had in previous years.”

The Spanish Flu would go on to kill up to 55,000 people in Canada, around the same number of Canadian soldiers who died in WWI, which was coming to an end in the fall of 1918. As debates over what to do raged into October, the virus was already spreading throughout Toronto.

By Oct. 8, just three days after Hastings told The Star that there was “no need for hysterics,” hospitals started filling up with patients with Spanish Flu symptoms: fever, nausea, coughing, aches, diarrhea and more. Soon after, The Globe and Mail reported, “All the hospitals are filled, and some cannot take any more cases.”

Hastings and McCullough were wrong. They and the rest of Canada spent the next months battling what the world now refers to as the worst wave of the Spanish Flu — one of the deadliest diseases in human history by number of casualties.

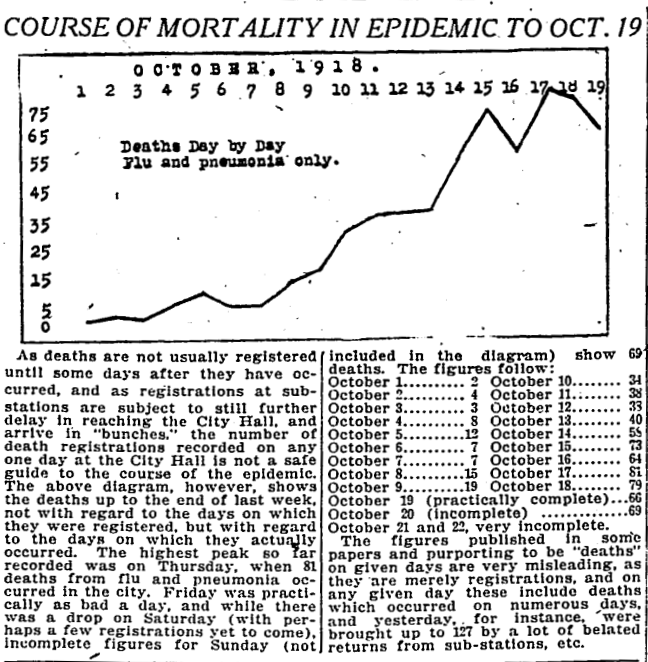

Statistics published on Oct. 23, 1918 in the The Toronto Daily Star.

Almost exactly a century later, Toronto finds itself caught again in the throes of a versatile disease capable of overwhelming the city’s public health system. COVID-19 refuses to submit to over a century of scientific, medical and technological progress, criss-crossing the world with multiple variants — each seemingly better adapted than the last.

But unlike the early 20th century, today’s Toronto and Canada aren't reeling from four years of global war. Hundreds of thousands of Canadians were drafted during WWI. Resources, including hospitals, doctors and nurses, were stretched thin. Yet the war also created a unifying effect at home.

Victory Loan drive with tank Britannia in front of City Hall, looking east, on May 6, 1919.

Many women volunteered as nurses or community workers aiding families who needed help during the war and then the pandemic. Soon, a sprawling volunteer structure coalesced in what was then an upstart Toronto with a population of barely one million people. It was this now-forgotten relief structure that faced down the Spanish Flu, carried into Canada by returning soldiers. Today’s Toronto has almost tripled in population, but there’s no organized or centralized volunteer structure that grew alongside to help with today’s COVID-19 pandemic.

The civic initiative displayed a century ago contrasts with Toronto’s COVID present, when crowds of anti-vaccine and anti-vaccine mandate protestors harass front-line health-care workers outside hospitals, galvanized by misinformation- and disinformation-spreading social media platforms that were supposed to provide us with connection. Instead, polarization overshadows today’s community care and mutual-aid efforts.

Canada was even thrown into a contentious federal election on Sept. 20, 2021, as Canadians reeled from the impact of the pandemic and COVID-19 variants named after the Greek alphabet continued dominating headlines. Cases rose and fell, then rose again. By March 21 of this year, Ontario lifted all mandates for most indoor settings, including those for vaccines and masks — not too long after anti-vaccine mandate protesters drove a trucker convoy into downtown Ottawa to occupy it for weeks on end.

Things looked different in Toronto the last time a global virus made its way here 104 years ago. A much more public and official volunteer structure was erected by those who didn’t have social media to help them organize.

So, how did they do it?

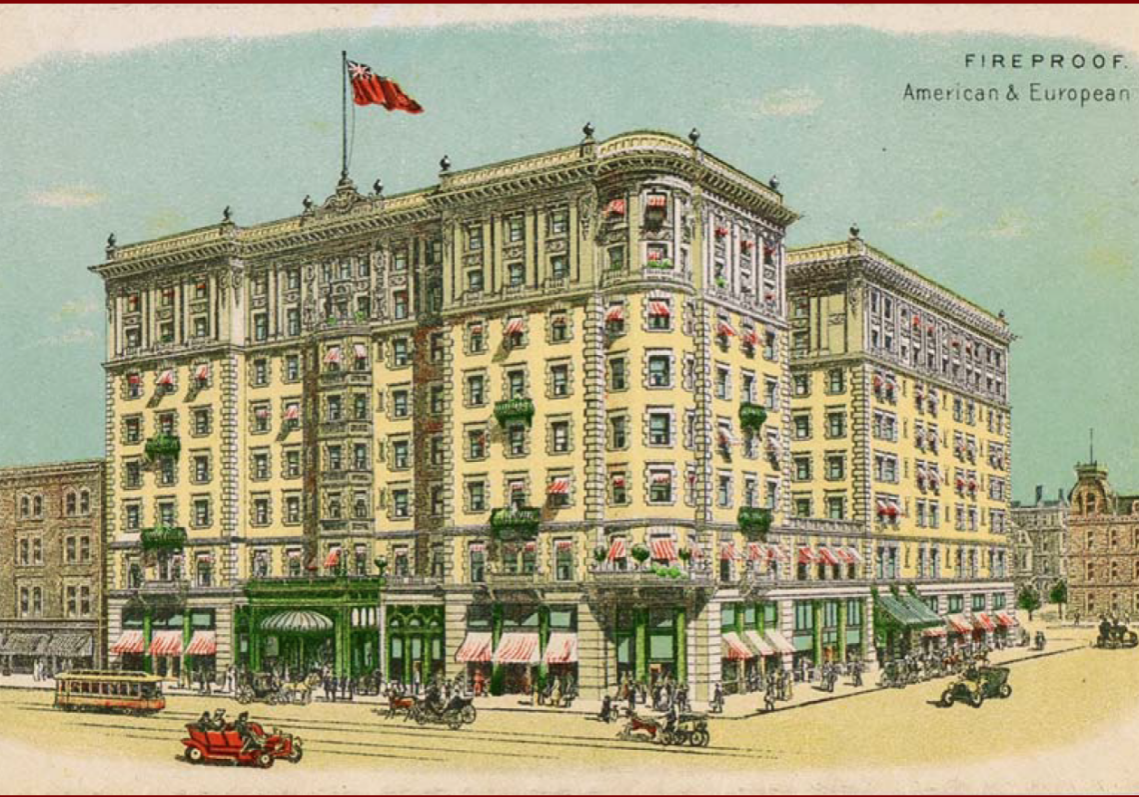

The King Edward Hotel on King Street in the early 20th century.

TORONTO 1918: RESPONSE

At around lunchtime on an anxiety-filled Tuesday in October 1918, several well-connected members of Toronto civil society filed into downtown’s King Edward Hotel just east of Yonge and King Streets.

They had arrived for an important meeting. At this point, the Spanish Flu had officially occupied the city, and hospitals were overwhelmed. Although so many had made it through WWI, they were faced with yet another battle — one with an invisible enemy.

Torontonians forced to battle this virus at home had less access to medical care, and it was to these homebound people that the King Edward meeting turned its attention. In attendance were leaders of the Toronto Rotary Club, founded for businessmen and other professionals to better serve their communities. Hospitals were turning people away, so Toronto’s leaders had to come up with a system to get them help.

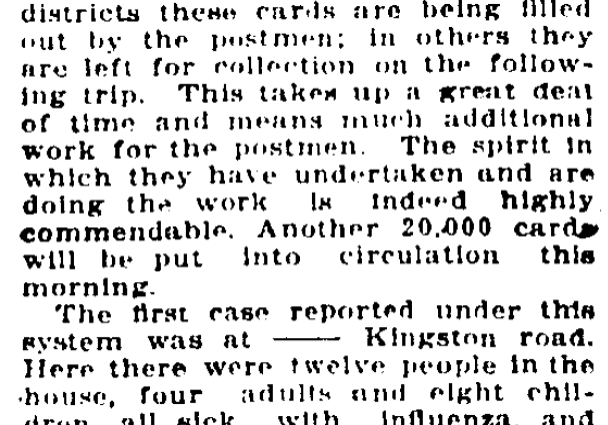

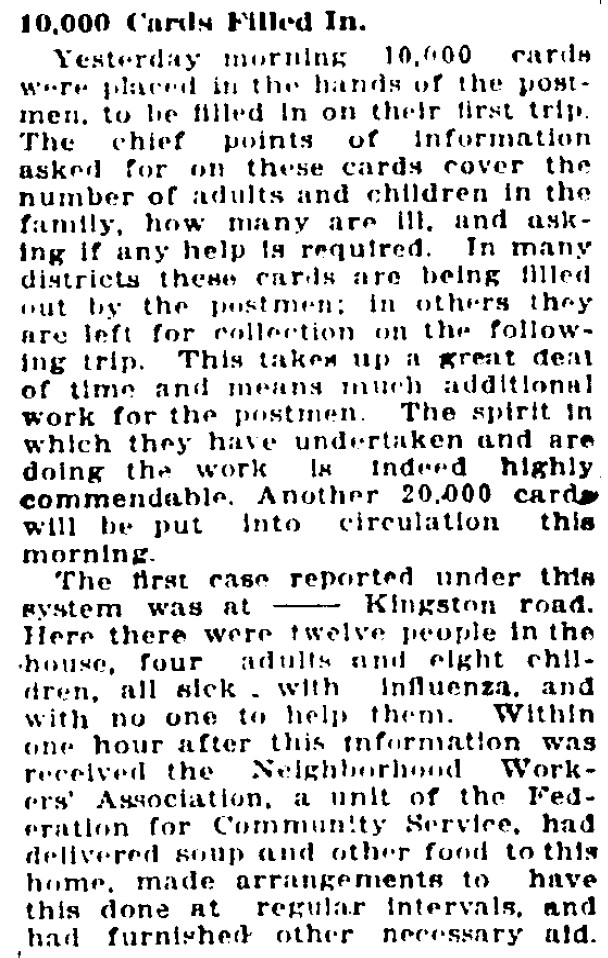

Health educator and medical anthropologist Dr. Karen Slonim, whose 227-page PhD dissertation provides an exhaustive analysis of Toronto’s response to the Spanish Flu, cites several Globe reports at the time about how postal workers were furnished “with cards designed to ascertain the number of children and adults within a household, how many were ill and if help was required.”

After the federal government okayed the deployment of these postal workers, 10,000 cards were given out on the first day, and 30,000 in just a few days.

The Globe and Mail's Oct. 24, 1918 edition.

“The first case reported under this system was from a home on Kingston Road,” Slonim paraphrases in her dissertation. “Twelve people resided within this dwelling, four adults and eight children, all sick with influenza and with no one to help.”

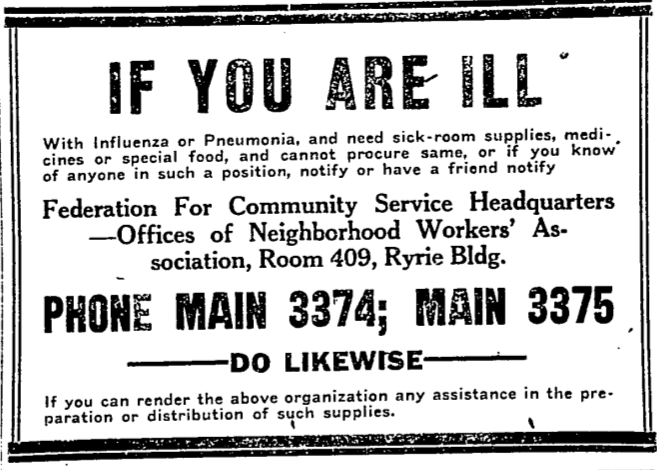

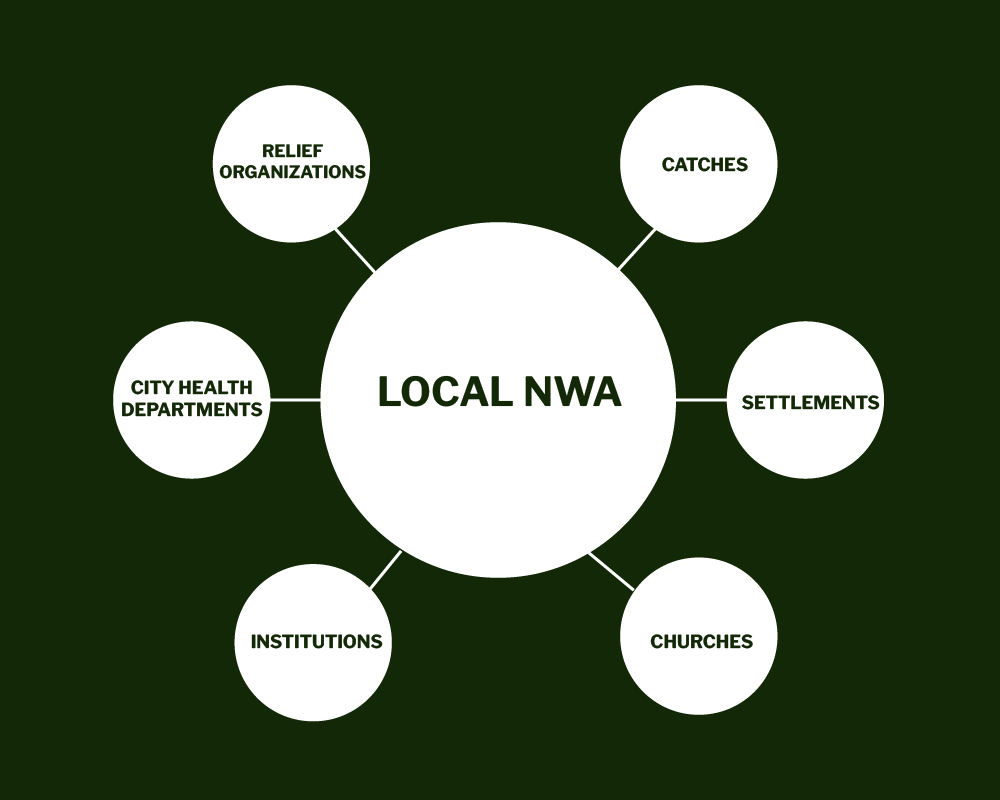

One of the most important groups in the overall relief effort was the Neighbourhood Workers Association (NWA), known today as Family Service Toronto. Various NWA chapters connected with local groups, particularly churches, to provide specific relief. Volunteers associated with the organization used public kitchens to provide food for families in need.

Neighbourhood Workers' Association ad in The Toronto Daily Star's Oct. 23, 1918 edition.

They also helped respond to information collected by the card survey system, including the request from the big family on Kingston Road mentioned in Slonim’s dissertation. According to an October 1918 report in the Globe, the NWA “had delivered soup and other food to this home, made arrangements to have this done at regular intervals, and had furnished all other necessary aid.”

The Globe even put a call out in their pages, instructing people to fill out the cards to receive aid. Here are two examples from its Oct. 24, 1918 edition:

The NWA chapters were effective at contributing to such efforts in Toronto partly because they themselves were so organized. There was a bureaucratic structure put in place to cover various neighbourhoods, and to connect with and complement the efforts of other local organizations. Everything fanned out from a “Central Council” in charge of NWA chapters across the city. These local chapters would in turn coordinate with other organizations on the ground, including government departments, to accommodate the specific needs of particular families.

Case in point: The NWA convinced Toronto’s then-education board to provide two kitchens in the Central Technical School (at Bathurst and Bloor Streets) and the Annette Street School (at Dundas Street West and Runnymede Road) for volunteers to make meals for the needy. After some heated debate over the use of fuel, the board conceded. Eventually, over 750 families received food from the Central Technical School’s kitchen alone.

Data visualization of a local NWA's network in Karen Slonim's 2010 PhD dissertation on the Spanish Flu in Toronto.

Data visualization of the NWA network in Karen Slonim's 2010 PhD dissertation on the Spanish Flu in Toronto.

Toronto’s NWA chapters managed 24 depots that provided goods and services throughout the city. On average, NWA’s affiliates visited 500 homes a day. This level of organized volunteering was made possible thanks to the NWA’s existing structure. By 1919, the NWA oversaw around 200 groups manned by some 600 staff, including volunteers, according to the association’s then-general secretary Frank N. Stapleford.

No timeline today would include any news stories featuring such well-organized relief structures since none exist. Nowadays, anyone can buy or search for whatever they need using a computer or phone. Indeed, Google Trends revealed that “covid vaccine” and “covid testing” were the top two searched terms for “near me” locations last year.

The war-driven collectivism we saw in 1918 has no parallel a century later. Government and health officials today emphasize personal quarantining and keeping to yourself. Both pro- and anti-maskers, as well as pro- and anti-vaxxers, are animated by their own versions of individualism — one is about maintaining health, the other about maintaining freedom.

But this individualist reality hasn’t stopped some people from taking matters into their own hands, to make the best out of a very challenging situation.

TORONTO 2020: RESPONSE

In March 2020, right when it became obvious that the COVID-19 virus would lead to a full-blown global pandemic, Toronto’s Mita Hans started worrying about how her elderly neighbours were going to make it through city streets filled with anxious crowds.

Torontonians were flooding grocery and convenience stores. Masks and alcohol wipes were all sold out. The arrival of COVID-19 brought out the human instinct for self-preservation, with photos of shoppers panic-buying and hoarding toilet paper now a recognizable meme.

So, Hans decided to visit her neighbour to ask if she needed anything. A quick rebuff was followed by a warning for Hans to stop “scaremongering,” as the neighbour felt as if she was deliberately trying to frighten her. Undeterred, Hans expressed her concern again and again, eventually bringing groceries to her neighbour’s door multiple times.

This sense of civic compassion preoccupied Hans, a community organizer and disability worker in her 50s. But what she saw online and in the headlines was dispiriting. Scaremongering actually seemed like an apt term: mass deaths, economic ruin, lockdowns, social distancing.

“Everything we were seeing in the media was sparking absolute fear,” Hans told The Green Line over the phone. “How are we going to get through this?”

This spark of civic responsibility animated Hans just as it had motivated those who risked their lives 104 years ago to care for the vulnerable during the Spanish Flu pandemic. But unlike that earlier era, which was buoyed by a collectivist war effort, the 21st century has seen the advent of individual mass consumption and increasingly atomized, digital lives.

The world has changed.

There’s no organized fleet of volunteer nurses. No doctors making house calls. No armies of people bringing hot soup to those too sick to get out of bed. No structure in place to make any of this happen. That’s why Torontonians like Hans took matters into their own hands.

“This pandemic exposed the cracks in the system,” she said. “It shined a very bright spotlight on who falls through the cracks…predominantly Indigenous and people of colour, predominantly those under the poverty line and are like one paycheck away from deeper waters than they can contend with.”

Data provided by Toronto’s health authorities confirm these observations. Seventy-two per cent of reported COVID-19 cases up until Sept. 30, 2021 were from people who identified as racialized. Sixty-six per cent of those hospitalized due to the disease were also racialized.

Toronto Public Health first released its COVID-19 neighbourhoods map months after the pandemic was declared, showing which areas of the city were worst hit by the virus. Sixteen neighbourhoods in the city’s Northwest region (Steeles Avenue to Eglinton Avenue; Dufferin Street to Highway 427) had the highest rates.

According to a 2018 report by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), an Ontario-based public health data and research nonprofit focused on accessibility, neighbourhoods with higher COVID-19 rates in Toronto have traditionally lacked access to healthcare.

This includes both primary care, which is the ability to relay initial health concerns to professionals like family doctors, and specialist care. Neighbourhoods in or near the centre of the city have more access, but that starts to drop off sharply in places like the previously mentioned Northwest neighbourhoods or parts of Scarborough. Some of these neighbourhoods also have a higher proportion of Black residents, far above the city-wide average of 8.9 per cent.

The federal government looked to mitigate the socioeconomic fallout of COVID-19 by providing the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), which provides financial support to employed and self-employed Canadians directly affected by the pandemic. But even with $2,000 a month, it’s tough to live in a city as expensive as Toronto.

“There was no plan B or even a plan A to help the vulnerable, so volunteerism had to step in to help keep our neighbours afloat,” Hans explained.

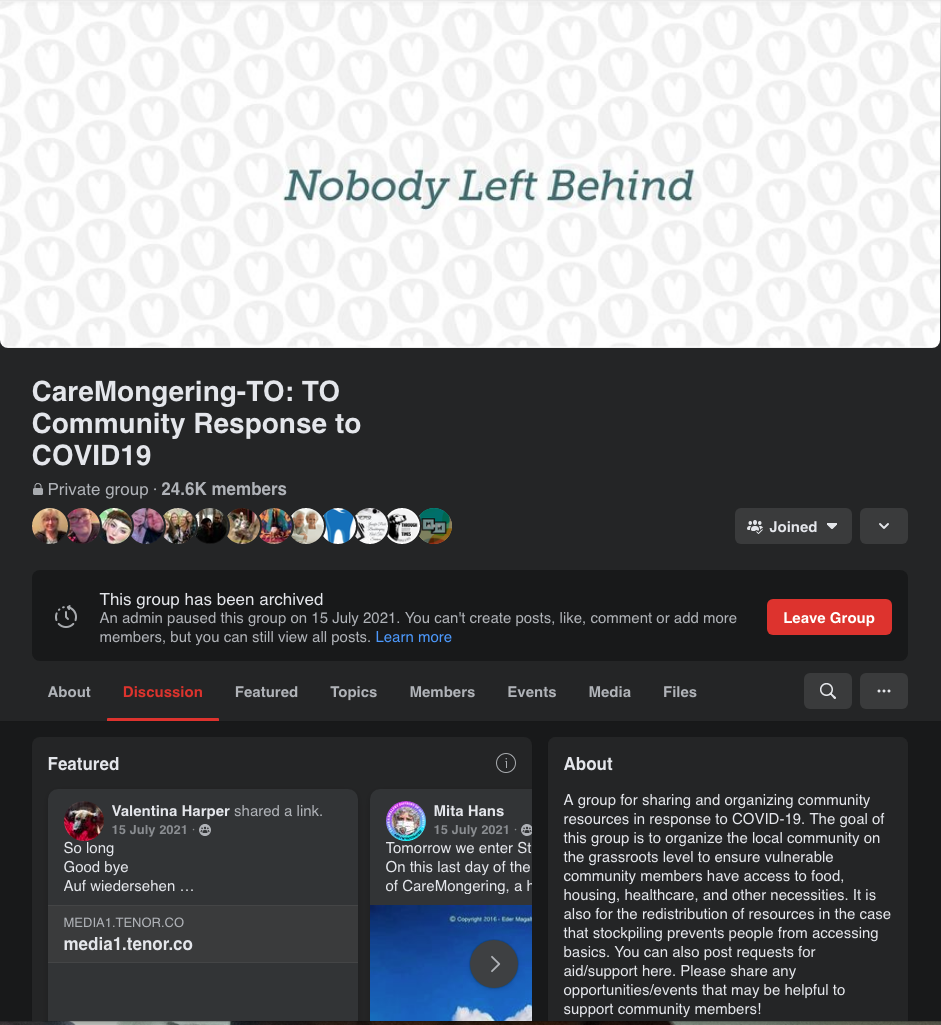

So, she called up some friends and started a mutual-aid hub for her community. Located mostly on Facebook, the group was used for everything from “sharing the current medical information, to directing people to the CERB funding, to filling in the gaps of food support, to sharing information on resources from YouTube, to keeping kids occupied, to Zoom seminars that were for better health,” she said. “It ran the gamut.”

Through it all, Hans thought back to all the fear. She thought about her neighbour telling her to stop “scaremongering,” and came up with a name for what she and her friends were doing.

“Care-Mongering, the name, gave a very handy alternative of something we can all do,” Hans said. “People reacted to it, gravitated to it, because yes, this is something we can do. It's much easier dealing with this darkness when we're doing something and are actively engaged.”

Care-Mongering Toronto, which was the world’s first mutual-aid platform to serve pandemic-specific needs, is now an archived Facebook group. At its peak, it had over 24,000 members and sparked a broader movement. Within a week or so of launching, similar groups started up in countries thousands of kilometres away, including Malaysia, where people delivered money and food to groups of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar.

In Toronto, Care-Mongering became an important space for people to coordinate city-wide efforts. For instance, Hans said a brigade of bikers connected with The 519, a downtown community centre serving the city’s LGBTQ+ communities, to provide hundreds of meals per week.

People who needed help tagged their posts in the Facebook group with #iso — “in search of” — while those who could provide help tagged their posts with “offer.” The creativity and ingenuity of group members’ initiatives went far beyond handing out pocket change to the less fortunate.

The Care-mongering Toronto Facebook group, which was archived on July 15, 2021.

Today’s more freelance aid initiatives don’t have the benefit of building on years of neighbourhood volunteer groups and structures that were erected during wartime. Nowadays, efforts have to be built from scratch and are more temporary; whereas initiatives back then, like the NWA, have lasted.

Given these differences, retired Canadian history professor Heather MacDougall cautions against drawing parallels between volunteer efforts during the Spanish Flu and those during COVID-19.

“In 1918, the public accepted restrictions and hoped for a vaccine, but were inured to death and disease in a way that current society is not,” explained MacDougall, a former University of Waterloo professor who specializes in the history of medicine, public health and health policy. “They drew on years of voluntary activity to respond to the pandemic.”

This illuminates the ironic reality of 1918. War, a violent and often divisive cataclysm, gave rise to altruistic measures and structures. Torontonians caring for their neighbours saw it as helping their country face down the enemy. War, at least back home, had the counterintuitive effect of sowing more social harmony.

At least one volunteer in 1918 who threw herself into the cauldron of Toronto’s overtaxed hospitals was actually a pacifist, thanks to what she saw as the horrific consequences of WWI. But unlike Hans, who had to build everything from scratch, this young woman plugged herself into an existing and growing structure of medical relief that came together during wartime.

She wasn’t just an individual striking out on her own, making ad hoc efforts in the name of civic duty. Instead, she joined a fleet of like-minded women who embodied the spirit of the age.

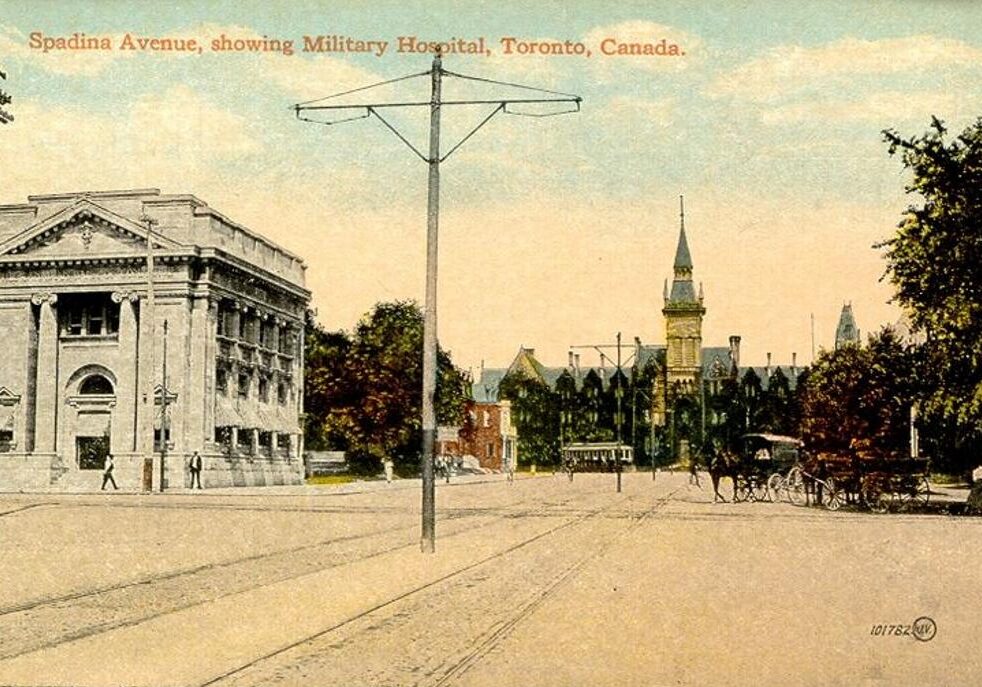

A postcard of Spadina Avenue at College Street, with the Spadina Military Hospital (now known as 1 Spadina Crescent) in the background.

TORONTO 1918: INDIVIDUAL DUTY

Today, 1 Spadina Crescent is conspicuously located in the middle of downtown Toronto’s urban landscape, an eye-catching Gothic structure housing part of the University of Toronto’s faculty of architecture.

In 1916, people filed into the building for a very different reason. As wounded soldiers from WWI overwhelmed Toronto’s hospitals, 1 Spadina — until then a theological college — was refurbished into the Spadina Military Hospital. The wartime facility depended on a fleet of nurses and nursing aides, the latter of which were almost all volunteers.

About 2.5 kilometres east of 1 Spadina, a young woman walked from her temporary residence at the St. Regis Hotel on Sherbourne Street to the streetcar stop near Sherbourne and Carleton Streets every single morning in 1918.

Lithe and pale with a shock of reddish auburn hair, she would’ve been dressed in a long, white gown that reached down to her ankles, along with a matching cap. The streetcar ride took her 15 minutes west to Spadina Military Hospital, where she joined a small army of aides who trained for just a few days before working 12-hour shifts to care for the ill and wounded.

Portrait of Earhart as a volunteer nurse in Toronto.

Before becoming the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic in 1932, and before being infamously immortalized by disappearing into the Central Pacific in 1937 with her Lockheed Model 10-E Electra airplane, Amelia Earhart dutifully tended to the veterans of Spadina Military Hospital. It was in Toronto where she first caught the flying bug, chatting with wounded pilots who traded war stories.

Earhart first arrived in the city from Philadelphia as a 20-year-old visiting her younger sister Muriel, but decided to stay after seeing the results of WWI. She tended to shell-shocked soldiers missing their arms and legs — and sometimes more.

“She was very young at the time, and doing nurse's aide type of work was really all she could do,” said Amy Morissey Kleppner, Muriel Earhart’s daughter, who’s now in her 90s and living in Vermont.

Kleppner’s strained voice was barely audible over the phone, but just like her mother, she spent decades documenting her aunt’s life. “[Earhart] thought that was the right thing to pursue, given the horrors she saw of the wounded. The whole experience made her a lifelong pacifist,” she explained.

The Globe and Mail's Oct. 19, 1918 edition.

Earhart was one of thousands of women who volunteered this way, attending a few days of nursing lectures at Spadina Military Hospital before getting tossed into bloody infirmaries. She was part of the Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs), which was made up of women who stepped up as medical aides, ambulance drivers and clerks to help relieve an overworked healthcare system. Earhart began volunteering as an aide in 1917 when she was 20 years old.

“I think she was moving into that direction of social consciousness and awareness perhaps at a young age,” Kleppner says. “By the time she got to Toronto, she felt a very strong opposition to war in any form. But all she could do at that time was to try and lessen the suffering of those around her.”

Earhart, like many others at the time, answered the call of municipal and provincial officials to attend emergency lectures set up across Ontario to become either nurses or nursing aides. Prominently among them were also church sisters from the Anglican Church and Diocese of Toronto who nursed the wounded and ill. These nurses worked around the clock, and sometimes contracted the virus themselves.

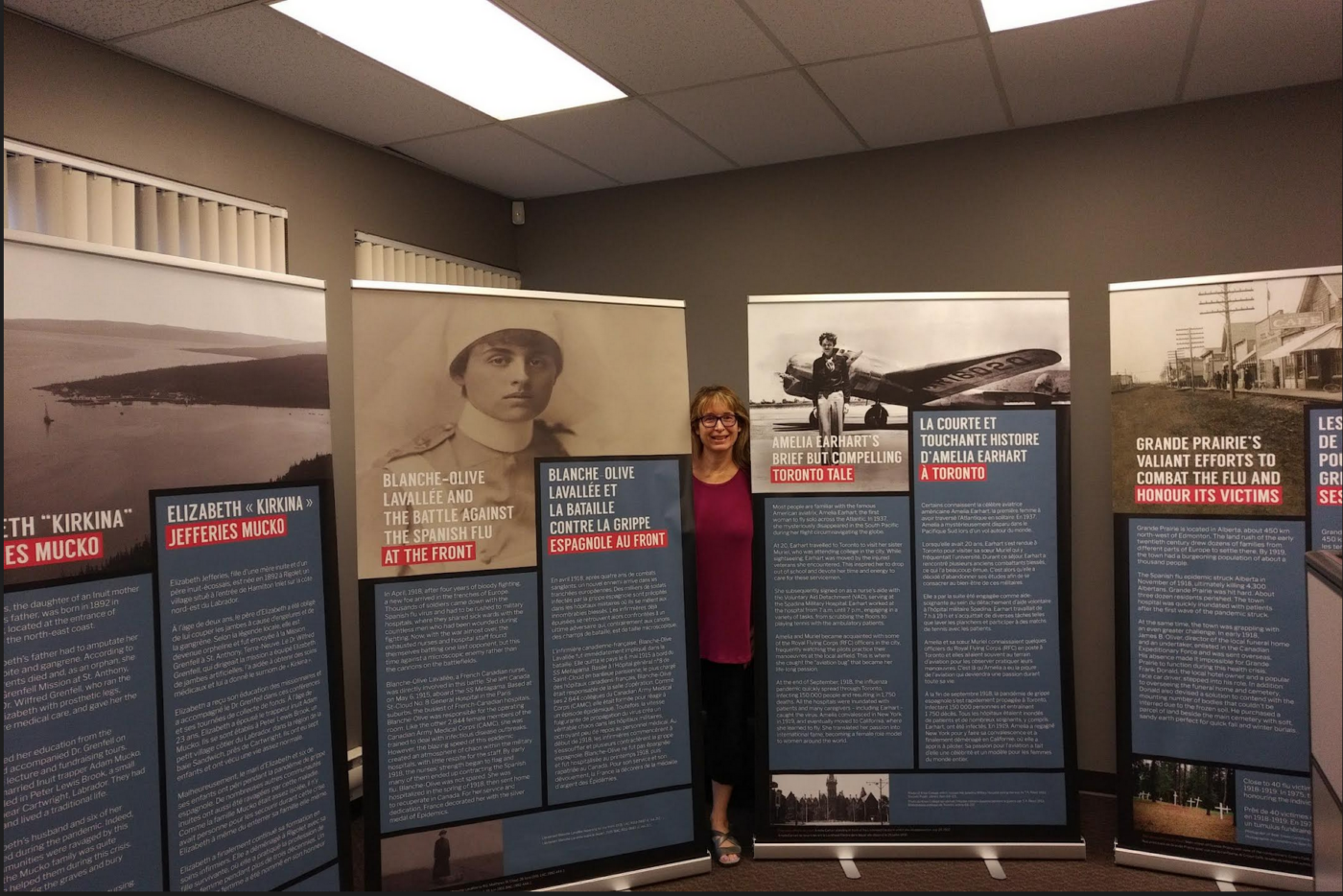

Ellen Scheinberg with her “Teaching About Spanish Flu” exhibit in 2018, a project by Defining Moments Canada.

By Armistice Day on Nov. 11, 1918, Toronto’s hospitals had already gone from being overflowing with wounded soldiers to overflowing with influenza patients. Extra space had to be made in hospitals for those who contracted Spanish Flu. Toronto General Hospital, for example, absorbed over 650 patients in October 1918. At certain points, there were eight to 10 deaths a day. The risks were higher for those working shifts after the war, but Earhart increased her workload during the pandemic by picking up extra shifts.

“Earhart also spent considerable time assisting in the kitchen and the medical dispensary,” writes Toronto-based heritage consultant and historian Ellen Scheinberg, a former archivist at the National Archives of Canada (now Library and Archives Canada) and current president of Heritage Professionals.

Earhart’s stay in Toronto came to an abrupt end when, during one of her shifts, she contracted the Spanish Flu herself. That led to pneumonia and sinus infection, which required surgery, according to Scheinberg. Earhart then went to New York to recover in 1919.

Today, her fateful stay in Toronto is all but forgotten, save a small plaque placed where the St. Regis on Sherbourne Street used to be. Earhart’s years here marked a unique, somewhat quaint time when war and social cohesion co-existed.

Women volunteers pose for a photo in front of Queen's Park after completing a lecture on nursing influenza patients during the Spanish Flu.

TORONTO 2022:

CIVIC COMPASSION?

Toronto didn’t implement any major lockdowns in response to the Spanish Flu. Various officials at the time thought it would be a bad idea, though it’s unclear how this decision ultimately affected the number of sick and dead. It did, however, allow for easier access into the lives of other Torontonians.

Today’s more siloed world makes social distancing and quarantining easier to accept. Alongside this exists a polarizing social and ideological divide between those who support government measures to fight COVID-19 and those who don’t trust anything the government says or does. More extreme voices among the latter are tied to conspiracy theory-driven movements online. The result between many neighbours isn’t compassion, but rising tension, suspicion and anger.

“It is not [only] what we do when people are sick; it is how we talk about them that [also] matters,” said Karen Slonim, the public health educator and medical anthropologist. “When we blame them for getting sick or focus on their ability to make us sick, we water down our humanity. Instead of caring for each other we create a culture of fear and blame and that does not help anybody.”

This fracturing culture of blame and tribalism will be challenging to overcome in the current and post-COVID era. The information age that was supposed to facilitate better human connection has gradually separated ideas and arguments from the human faces behind them.

Torontonian’s non-digital volunteer efforts in response to the Spanish Flu hints at other possibilities. Despite having no internet, social media or cellphones, people were more comfortable getting involved in each other’s lives during times of crisis.

“Over the last two years, what is shocking to most isn’t the inequality that has been revealed over and over and over again,” said Yvonne Su, the York University professor. “It’s that no one cares to change it.”

Inequality often comes back with a vengeance after crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic, she added.

By then, slogans like “We are all in this together” will fade away, but what does that mean for the common good? Perhaps we should learn from this pandemic to challenge prevailing structures that encourage polarizing individualism, and instead work together for the collective good. Indeed, we can take inspiration from the fact that many Torontonians succeeded in doing just that a century ago, when disease ravaged our home.

Here's your chance to support the only independent, hyperlocal news outlet dedicated to serving gen Zs, millennials and other underserved communities in Toronto. Donate now to support The Green Line.

PART 3

Learning to breathe again: How to live with COVID and compassion in Toronto

A community event and Story Circle hosted by The Green Line.

About the Event

It's hard to ignore the worsening inequality and infighting that COVID-19 has highlighted over the past two years in Toronto. That's why The Green Line is inviting action-oriented community members like you to brainstorm ways we can motivate our fellow Torontonians to form stronger relationships and support networks within their communities, so everyone can work together to fill in gaps in our city's public health system. RSVP now for our virtual event.

Events are an essential part of our Action Journey. We want to empower Torontonians to take action on the issues they learn about in The Green Line — so what better way to do that than by bringing people together? From community members to industry leaders, anyone in Toronto who’s invested in discussing and solving the problems explored in our features is invited to attend. All ages are welcome unless otherwise indicated. Our only guidelines? Be present. Listen. Be kind and courteous. Respect everyone’s privacy. Hate speech and bullying are absolutely not tolerated. At the end of the day, if you had fun and feel inspired after our events, then The Green Line team will have accomplished what we set out to do. Any questions? Contact Us.

STEVEN

ZHOU

ELLEN

SCHEINBERG

Dr. Ellen Scheinberg is a historian and president of Heritage Professionals, a consulting firm specializing in archival, museum and information management services. She has published in a variety of areas, including archival studies, women’s history, Jewish studies and immigration history. Several years ago, Scheinberg produced a series of short pieces documenting the history of the 1918-1920 Spanish Flu in Canada.

NAHEED

DOSANI

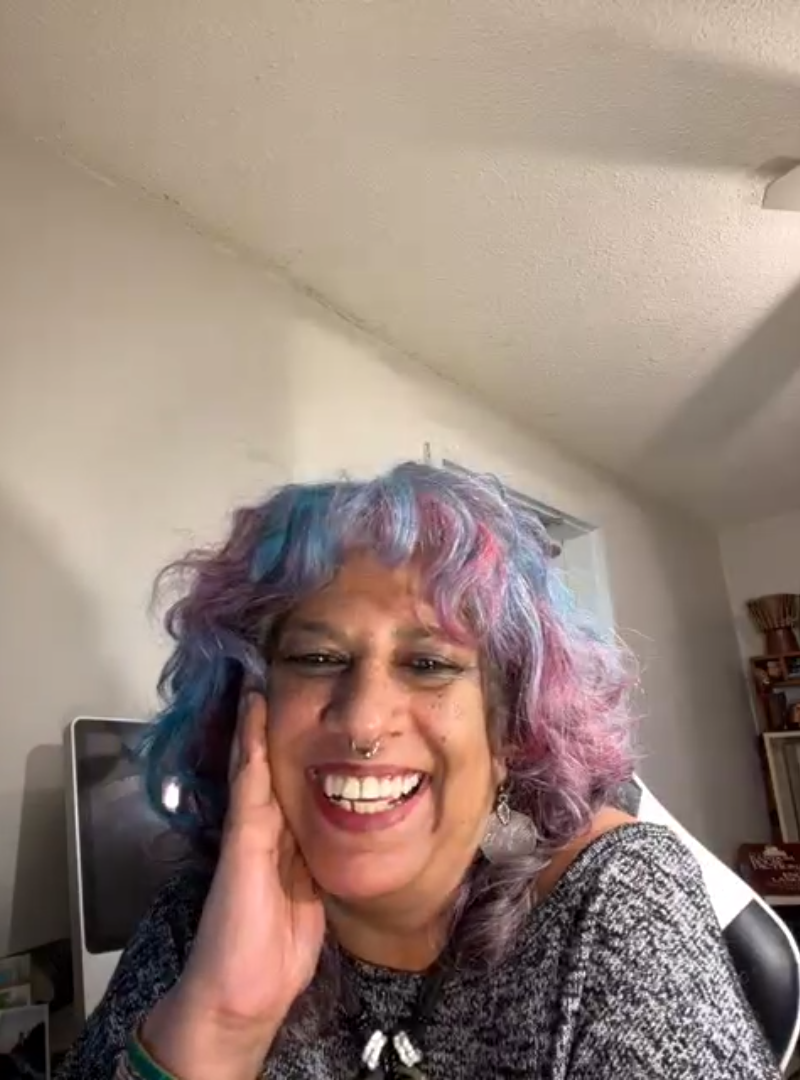

MITA

HANS

Mita Hans is the co-founder of Care-Mongering Toronto, the world’s first mutual-aid platform to serve pandemic-specific needs. She is also a frontline health worker and advocate who believes that people come before profit. Mita is passionate about making Toronto, the city she loves, live up to what she feels is its best — but yet unmet — potential.

KAREN

SLONIM

Dr. Karen Slonim is a health educator and medical anthropologist whose 227-page PhD dissertation provides an exhaustive analysis of Toronto’s response to the 1918 Spanish Flu. Karen holds a PhD in anthropology from U

PART 4

RECOVERING TOGETHER: Community over apathy

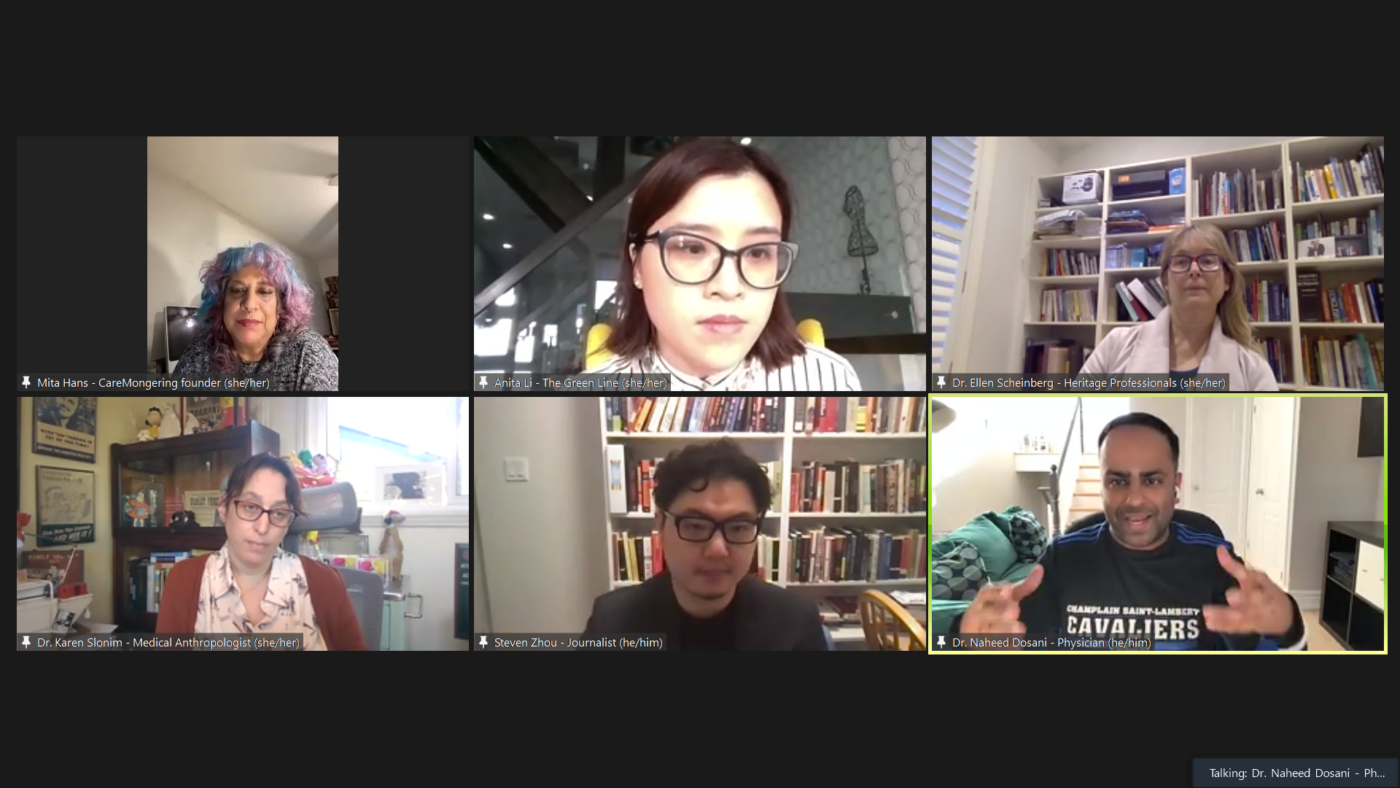

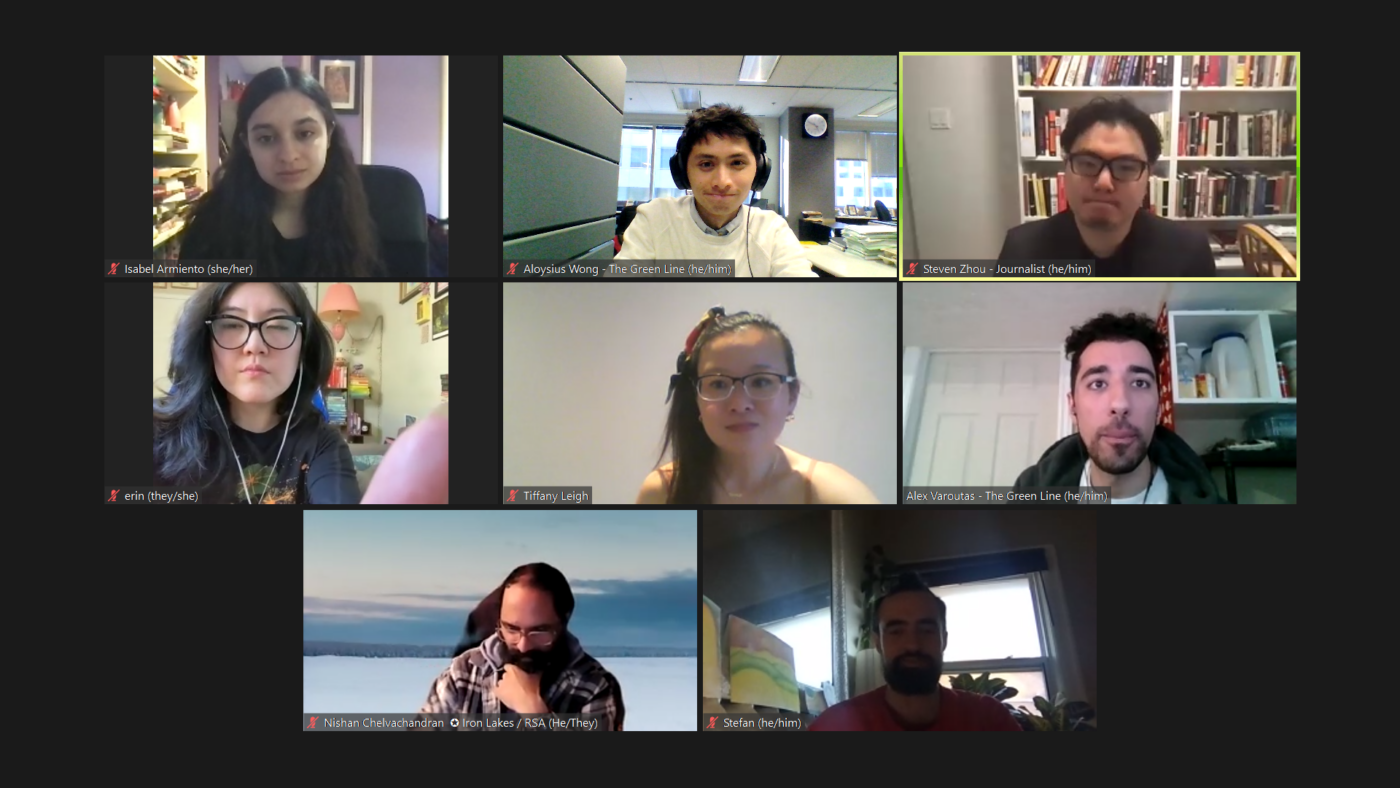

Event Overview

See what you missed

from our latest event.

Our community members brainstormed ways to motivate their fellow Torontonians to form stronger relationships and support networks within their communities, so everyone can work together to fill in gaps in our city's public health system. Compiled by Aloysius Wong.

Dr. Naheed Dosani speaks on a panel at The Green Line's inaugural Action Journey event, Learning to Breathe Again: How to Live with COVID and Compassion in Toronto, on Thursday, April 21.

Student Sean Meral shares how he lived through the first two years of the pandemic in a Story Circle at The Green Line's Action Journey event about COVID re-entry.

Mita Hans, founder of Care-Mongering Toronto and a panelist, at the Action Journey event.

The Green Line reporter Alex Varoutas moderates one of the Story Circles in a breakout room at the Action Journey event.

SOLUTIONS

ACTIONS

Do something about the problems that

impact you and your communities.

Host a

Community Gathering

Bring your community together with a BBQ, picnic or other social event.

Write to

Your MPP

Contact your Member of Provincial Parliament to advocate for anything from legislated sick days to better safety measures in long-term care homes.

Communicate

With Intent

Follow best practices when communicating COVID-related information — whether or not you're in a position of authority.

Join Our

Community

Continue the conversation with other Green Line community members.

Attendees pose for a group photo at the end of the Action Journey event.

Supporting The Green Line means supporting Toronto. Join our membership program today, so you can redefine our city as you see it.